Western Amnesia

and The

Kidnapping of Children by Boko Haram

(August 2015)

Girls Kidnapped by Boko Haram

Boko Haram has recently received considerable international condemnation as a result of their kidnapping more than 200 Nigerian girls. This has been done as part of Boko Haram’s opposition to the imposition of Western education and values into the predominantly Muslim region of northern Nigeria. Of course, the members of the movement are presented as fanatical, uncivilized and inhumane for undertaking such an action.

Interestingly, much of this criticism comes from Western nations, who have been the most egregious violators of the rights of native peoples. There is hardly a single country in the entire world that has not at one time or another been invaded and/or colonized by a Western power, most notably Great Britain, France and the United States. Furthermore, three Western countries —Australia, the U.S. and Israel— have a rather ignominious history of maltreatment of their indigenous populations, involving terrorism, disenfranchisement and ethnic cleansing. Two of these countries --the U.S. and Australia— even carried our formal government programs of capturing native children, removing them from their homes and placing them in government-run institutions where they could be better indoctrinated into the language, values and ideology of the national society (much the same thing that is being done by Boko Haram).

* * * * *

Scene from the film, Rabbit-Proof Fence

Australia

The 2002 film,

Rabbit-Proof Fence, tells the story of three Aboriginal girls and their trek across 1,500 miles of Western Australia in an attempt to escape from the Moore River Detention Center near Perth in Western Australia. The girls had been taken from their families as part of a systematic government policy to separate "half-caste" children from their communities, and place them with white families. The name of the film (and the book from which the film is adapted), comes from the fact that the three girls followed the fence constructed to limit the spread of rabbits. One girl was recaptured, but the other two made it all the way home. While it is not certain how many children were taken from their families, Aboriginal authorities place the figure over 30,000; others place the figure much higher."White welfare officers, often supported by police, would descend on Aboriginal camps, round up all the children, separate the ones with light-colored skin, bundle them into trucks and take them away. If their parents protested, they were held at bay by the police. Sometimes, to avoid harrowing scenes of parents clinging to the sides of the trucks, and to frustrate attempts to hide the children when the trucks drove into the camp, the authorities resorted to subterfuge. They would fit out the back of a truck with a wire cage and a spring door — like an animal trap. Then they would park the truck a short distance from the camp and lure the children into the cage with sweets scattered on its door. When enough children were in the cage, they would spring the trap door and drive rapidly away.

Aboriginals tried to save their children by blackening their skin so that they did not look half-caste. "Every morning, our people would crush charcoal and mix that with animal fat and smother it all over us, so that when the police came they could see only black children in the distance," witness No. 681 told the National Inquiry into "stolen children" (1995-97). "We were told to be on the alert and, if white people came, to run into the bush, or stand behind the trees as stiff as a poker, or else run behind logs or run into culverts and hide."

There were also many instances of children being kidnapped by individual Australian settlers in order to provide themselves with servants. In addition, children were often separated from their families

in various missions across the country. They slept in dormitories and had very limited contact with their parents. This system helped convert the children to Christianity by removing them from the cultural influence of their own people.The removal of Aboriginal children intensified at the end of the 19th century. In 1905 Western Australia legislation established the office of the "Chief Protector of Aboriginals", who became the legal guardian of all Aboriginal children up to the age of 16. This position was held by one man, A.O. Neville, from 1915 to 1940. It was his office that implemented the "Stolen Generations" policy, as the removals became known. This program was only brought to an official end in 1970.

* * * * *

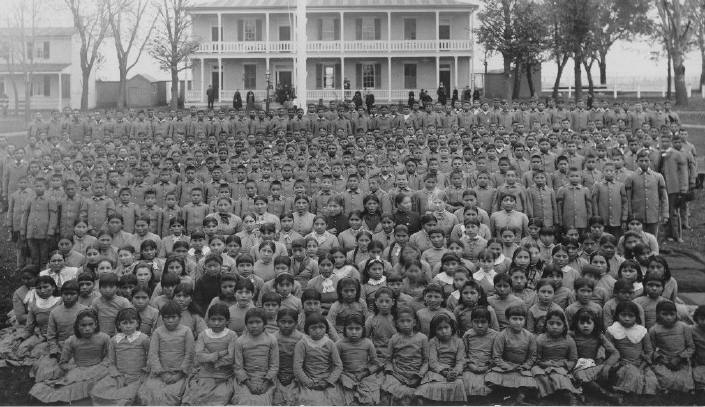

Native American Children at the Carlisle Boarding School

The United States

During the late 19th and 20th centuries, thousands of Native American children were forcibly removed from their homes and sent to boarding schools, where the motto of

Richard H Pratt, Founder and Superintendent of Carlisle Indian School the schools' was "Kill the Indian, Save the Man." At these boarding schools, children lost touch with their culture, traditions and families. Many suffered horrible abuse, leaving entire generations missing from the one place whose future depended on them —their tribes.Beginning in 1887, the federal government attempted to "Americanize" Native Americans, largely through the education of Native youth. By 1900 thousands of Native Americans were studying at almost 150 boarding schools around the United States. The U.S. Training and Industrial School founded in 1879 at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, was the model for most of these schools. Boarding schools like Carlisle provided vocational and manual training and sought to systematically strip away tribal culture. They insisted that students drop their Indian names, forbade the speaking of native languages, and cut off their long hair. Not surprisingly, such schools often met fierce resistance from Native American parents and youth.

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/4929/

Indian boarding schools, such as the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, PA (now the U.S. War College), were established in the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries to educate Native American children and youths according to Euro-American standards. They were first established by Christian missionaries of various denominations, especially in the American West. Subsequently, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) founded additional boarding schools to facilitate native assimilation into American society. Children were usually immersed in European-American culture through various appearance changes, including clothing and haircuts. Native children in these schools were forbidden to speak (and were frequently beaten for speaking) their native languages. Children’s traditional names were replaced by new European-American (Christian) names. The children were also introduced to Christian education and forbidden to practice their native religion, and again beaten when they did. The school experience was often harsh, especially for the younger children who were separated from their families. In numerous ways, they were encouraged or forced to abandon their Native American identities and cultures. The number of Native American children in the boarding schools reached a peak in the 1970s, with an estimated enrollment of 60,000 in 1973. Investigations of the later twentieth century have revealed many documented cases of sexual, physical and mental abuse occurring at such schools.

Many Native Americans have argued that the forced removal ("kidnapping") of Native children continues as part of official government policy. Nearly 700 Native American children in South Dakota are removed from their homes every year, sometimes under questionable circumstances. According to an

NPR News investigation, the state has failed to place these according to the law. The vast majority of native children in foster care in South Dakota are in nonnative homes or group homes, even though Native American foster families are available. "Of the hundreds of Native children in foster care in 2011, 87% were placed in non-Indian homes while Native foster homes went empty." The South Dakota's Department of Social Services (DSS) workers warn Native children that if they become emotional during a visit with their parents, the visits will be discontinued. Many of these foster children are eventually adopted by white families, removing them from their traditional communities. In 1978, Congress passed the Indian Child Welfare Act, which says except in the rarest circumstances, Native American children must be placed with their relatives or tribes, and that states must do everything they can to keep native families together. But 32 states, according to NPR, are failing to abide by the act in one way or another, and nowhere is this more apparent than in South Dakota. "Cousins are disappearing; family members are disappearing," said Peter Lengkeek, a Crow Creek Tribal Council member. "It's kidnapping. That's how we see it." http://www.npr.org/2011/10/25/141672992/native-foster-care-lost-children-shattered-families

* * * * *

The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction

In 1904, a group of New York nuns brought 40 Irish orphans to a remote Arizona mining camp, to be placed with Catholic families. The Catholic families were Mexican, as was the majority of the population. Soon the town's Anglos, furious at this "interracial" transgression, formed a vigilante squad that kidnapped the children and nearly lynched the nuns and the local priest. The Catholic Church sued to get its wards back, but all the courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court, ruled in favor of the vigilantes. --see Linda Gordon (2001), The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction.

I

n 1859, the New York Times termed urban orphans the "ulcers of society." By 1864, child welfare crusaders were advocating their adoption by rural families and sending trains full of orphaned and abandoned children westward. As Gordon documents in this compelling account, they were often dumped at the end of the line, where they were taken in by whoever needed or wanted a child for any purpose. By the end of the 19th century, the Sisters of Charity's New York Foundling Hospital was cleaning up this well-established practice by carefully matching children with families selected by parish priests. Focusing on the delivery of 40 "white" orphans to Mexican Catholic adoptive families in the Arizona mining towns of Clifton and Morenci in 1904, Gordon vividly describes how the Anglo women of the town. All of them Protestants became enraged and instigated a mass abduction of the children, often carried out at gunpoint. A trial ensued, pitting the Foundling Hospital against the Anglo powers of Arizona, which ended up in the U.S. Supreme Court. The Court held that the abduction was legal, and that placing the children with Mexican families had been tantamount to child abuse. In delineating the racial and religious dynamics in turn-of-the-century Arizona (including frontier feminism, the evolution of racial and class structures and the history of copper mining, labor disputes and vigilantism), Gordon reveals a great deal about the origins of "family values" in America. (Publishers Weekly)

People conveniently forget history when it becomes inconvenient.

* * * * *