.jpg)

On the Crucifixion of Jesus

William S. Abruzzi

(2021)

.jpg)

Each year on Good Friday, Christians around the world remember the trial and crucifixion of Jesus. However, the story as it is told in the four gospels --which present conflicting versions of that event-- is not how it likely happened. The earliest account of the trial is told by Mark and later modified by the other evangelists to fit their own theologies and to accommodate evolving beliefs about Jesus. As a result, while the core of the narrative remains relatively constant throughout the four gospels, the details of the story vary significantly. To understand what most likely happened, Jesus' crucifixion needs to be understood in its historical, rather than mythical, context.

For centuries, Christians have blamed Jews for Jesus' crucifixion. However, no serious scholar would support such a claim. Jesus was tried and executed by a Roman official (Pontius Pilate) likely for sedition against the state of Rome. This was a political crime, not a religious one, and Jesus received the punishment specifically reserved for such a crime under Roman law --crucifixion. This was a Roman punishment, not a Jewish one. Paul Winter (1974) noted that "The very fact that the Jews had no such institution as crucifixion was responsible for their not having a word for it." Indeed, there is no mention of crucifixion in Jewish Law or, for that matter, anywhere in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament). Stoning was the ultimate form of punishment commanded by Jewish Law. The

Mishna of Sanhedrin, the oldest known source detailing the appropriate forms of punishment prescribed by Jewish law, lists only stoning, burning, beheading, and strangulation as accepted forms of capital punishment (Rosenblatt 1956: 318). Josephus, the principle Jewish historian in 1st-century Palestine, does not report a single crucifixion during Herod's rule (40-4 BCE). It was not until Herod's death that crucifixion was instituted by the Romans, and only Roman authorities were permitted to conduct crucifixions. Publius Quinctilius Varus, the Roman legate of Syria, crucified some 2,000 Judean rebels who revolted against Roman authority following the death of Herod in 4 BCE. Expressing doubts even that Jewish leaders initiated the trial and execution of Jesus by pressuring the Roman authorities to execute him, Rosenblatt (1956: 319) comments quite clearly on the political implication this would have had for them: "To turn over a fellow Jew to the authorities of a hated alien government was informing, and informing against his own was one of the worst crimes that a member of an oppressed people could commit." Such an act would have placed the Jewish leaders in direct conflict with their own people, who were becoming increasingly agitated against the Roman occupation of their land.

Pontius Pilate

The gospel narratives are testimonials, not biographies, of the life of Jesus. Consequently, they need to be examined critically rather than accepted as historically accurate. This includes the events surrounding Jesus' trial and execution. The Gospel of Mark is the earliest gospel (c. 65-70 CE). Its version of the trial and crucifixion is, therefore, the original version upon which the other three gospels increasingly elaborated. (Paul, who wrote his epistles some 20 years before Mark's gospel was written, says nothing at all about Jesus' crucifixion other than simply referring to it having happened.) Mark's version of Jesus' trial --and, by extension, the others based upon it-- are illogical and without any factual basis. Mark's portrayal of Pilate, for example, is at complete odds with every piece of historical information known about him. The historical sources consistently describe Pilate as a stern government official who frequently demonstrated his toughness in dealing with the Jews. Philo, a Jewish philosopher and writer who lived from 20 BCE to 50 CE, characterized Pilate by "his venality, his violence, his thefts, his assaults, his abusive behavior, his frequent executions of untried prisoners, and his endless savage ferocity." (

Philo, Embassy to Gaius, par. 302).

On several occasions, Pilate undertook actions specifically designed to intimidate the Jewish population and its leadership in order to demonstrate his power and to assert his authority over them. On one occasion, shortly after Pilate arrived in Palestine, he had Roman standards bearing the images of the Roman emperor placed throughout Jerusalem. This was a violation of Jewish Law, which forbade the display of images in the holy city, especially those of Roman emperors who were considered gods by the Romans. On another occasion, he confiscated money from the Temple's sacred treasury to build an aqueduct. On this second occasion, he had his soldiers, disguised and armed with clubs, mingle with the crowd and instructed them to beat any protesters. According to Josephus (Antiquities 18.3.2), many Jews were killed by the soldiers and many others were trampled to death in the pandemonium that followed. Adding to descriptions of Pilate's cruelty, Luke (13:1) mentions "the Galileans whose blood Pilate had mixed with their sacrifices", indicating that Pilate had a group of Jews murdered while they were performing their religious duties. Pilate eventually had to be removed from Palestine and transferred to Gaul owing to constant Jewish protests over the severity of his rule. It is, therefore, highly unlikely that Pilate would have been pressured by the Jewish population into convicting Jesus of sedition, if he did not believe he was guilty.

In order to appreciate the lack of authenticity of the various gospel accounts of Jesus' trial and execution, it is important to note that the characterization of Pilate changes with each gospel's description of the trial. As each new version of the trial was written, Pilate becomes increasingly convinced of Jesus' innocence. In Mark, Pilate clearly condemns Jesus to death. In Matthew, he condemns Jesus, but only after the Jewish crowd insists that he crucify him. According to Matthew (27:24-26), Pilate washed his hands saying to the crowd, "I am innocent of this man's blood; see to it yourselves." (which, of course, a Roman governor would never say). This was simply Matthew's lead to having the Jewish crowd cry out in unison, "His blood be on us and on our children!", a clearly author-imposed quote that was used throughout the centuries to justify recurring Christian pogroms against the Jews. (see Abruzzi, Christian Origins of the Holocaust). In Luke (23:4), Pilate similarly proclaims Jesus innocent; "I find no basis for an accusation against this man." In John (19:6), Pilate states even more forcefully, "Take him yourselves and crucify him; I find no case against him." The Jews responded, "We have a law, and according to that law he ought to die because he has claimed to be the Son of God" (John 19:7). From then on, according to John (19:12), Pilate tried to set Jesus free, but the Jewish leaders kept shouting, "If you let this man go, you are no friend of Caesar. Anyone who claims to be a king opposes Caesar." portraying the Jewish crowd as demanding the Roman occupiers execute a Jewish nationalist. John (19:15) then has Pilate ask, "Shall I crucify your king?" to which the Chief priests incredulously respond, "We have no king but Caesar," Then, according to John (19:16), Pilate handed him over to them to be crucified, an action that would have violated Roman law. What we see in the four gospels, beginning with Mark and ending with John, is the increasing exoneration of Pilate in concert with the increasing damning of the Jews. Pilate's character was so completely distorted in the New Testament that both he and his wife have been declared saints in Greek, Russian and Coptic churches. St. Augustine even claimed that Pilate converted to Christianity, and tradition has it that he died a martyr's death (see Jensen 2003; Notley 2017).

Another problem with the gospel version of Jesus' trial is that It is unlikely that the trial was even a public event, but rather a quick and dirty affair done mostly behind closed doors. There was certainly not the philosophical discussion that took place between Jesus and Pilate in John's version of the trial, which stands in complete contrast with Mark's description of Jesus' near silence throughout the entire proceedings. Furthermore, none of the evangelists would have been present at the trial to report what took place, had a trial occurred. They were Greek, not Palestinians --all four gospels were written in literate Greek, not Aramaic, which was the language spoken in Palestine-- nor is there evidence that any of them ever lived in or visited Palestine. Finally, the gospels were written some 40-70 years after Jesus' death. Consequently, all four gospel accounts of Jesus' trial and execution must be treated as literary constructions written to promote specific religious beliefs.

The story of Pilate offering to release either Jesus or Barabbas as a Passover gesture to the Jews must also be rejected. No evidence exists of a custom of releasing one Jewish prisoner during the Passover, other than its mention in the New Testament. Not even Josephus, the principal Jewish historian of the day, mentions it. It is highly unlikely --indeed, incredible!-- for Rome to have followed such a practice in the most rebellious province in its empire (or in any other province, for that matter). The Roman government releasing a Jewish prisoner who had murdered Roman soldiers during an insurrection as a Passover gesture would be comparable to the Israeli government releasing a Hamas terrorists during Ramadan, or to the British government having released an IRA terrorist on St. Patrick's Day. Brandon (1967: 4) adds quite emphatically, "Mark presents Pilate, a Roman governor, not only as criminally weak in his failure to do justice, but as a fool beyond belief. . . . To have offered the people such a choice . . . [Jesus or Barabbas] . . . with the intention of saving Jesus, was the act of an idiot." Given the political climate at the time, the Jews, who were in constant revolt against Rome (see Horsley and Hansen 1985), would clearly have preferred to free a Jewish nationalist, such as Barabbas, rather than a man who the gospels claim said "Love the Romans" and "Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's."

Crucifixion

Crucifixion was considered the most demeaning and ignominious form of punishment in the ancient world.

It was reserved primarily for the lowest, most vile criminals. The punishment was primarily used on slaves and on subjects in colonized regions, such as Judea. Torture and crucifixion were rarely applied to Roman citizens and only to those found guilty of serious crimes against the state. Roman Law even forbade the torture of Roman citizens and stated that "no free Roman citizen should be tortured before condemnation." (Polonen 2004: 228). Polonen (ibid.: 232) adds, "no citizen could be tortured before his condemnation, and only plebian convicts could be tortured after it." A good example of the legal distinction made between a Roman citizen and a non-citizen is shown by Paul himself. When Paul was arrested following a disturbance caused by his preaching in Jerusalem, the soldiers had to let him go, due to his claim of being a Roman citizen.

. . . the tribune directed that he was to be brought into the barracks, and ordered him to be examined by flogging, to find out the reason for this outcry against him. But when they had tied him up with thongs, Paul said to the centurion who was standing by, "Is it legal for you to flog a Roman citizen who is uncondemned?" When the centurion heard that, he went to the tribune and said to him, "What are you about to do? This man is a Roman citizen." The tribune came and asked Paul, "Tell me, are you a Roman citizen?" And he said, "Yes." The tribune answered, "It cost me a large sum of money to get my citizenship." Paul said, "But I was born a citizen." Immediately those who were about to examine him drew back from him; and the tribune also was afraid, for he realized that Paul was a Roman citizen and that he had bound him. (Acts 22:24-29)

Josephus (

Jewish Wars 7.203) called crucifixion "the most wretched of deaths." In 70 BC, Cicero (In Verrem 2.5.165) referred to crucifixion as "that most cruel and disgusting penalty" and designated it the summum supplicium, i.e., the supreme penalty among Romans (ibid. 2.5.168). In his Moral Letter to Lucilius, Seneca (c. 4 BCE Ð 65 CE) commented on the agony of crucifixion.

Can anyone be found who would prefer wasting away in pain, dying limb by limb, or letting out his life drop by drop, rather than expiring once for all? Can any man be found willing to be fastened to the accursed tree [cross] long sickly, already deformed, swelling with ugly tumours on chest and shoulders, and draw the breath of life amid long-drawn-out agony? I think he would have many excuses for dying even before mounting the cross!

Cook (2014: 423-430) lists several features that were typically associated with crucifixions in the Mediterranean world:

--crucifixions were carried out by a public executioner or a military authority;

--crucifixions were frequently accompanied by various forms of torture;

--victims were often walked in chains to their place of execution, often designated outside the city;

--they might be "patibulated," (hanged on a gallows for public display)

--carrying the horizontal part of their cross to that place, where the vertical beam would already be in place;

--victims could be stripped, but were not necessarily naked;

--ropes or nails or perhaps both could be used to affix the victim to their instrument of torture;

--they could be upright or in different poses, such as upside down;

--the magistrate read the charge from a placard or titulus, which could then be placed on the cross;

--bodies could rot on crosses or be buried.

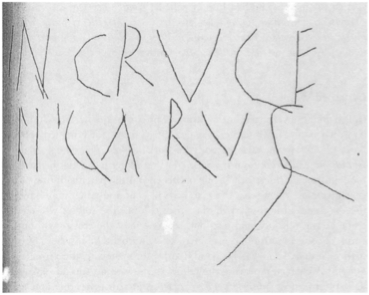

Crucifixion was considered

so disgusting and demeaning that graffiti has survived indicating it was used as

a form of curse. One inscription found on a wall in the Stabian Baths at Pompeii

proclaimed

Crucifixion was a typical slave punishment; some 6,000 members of Spartacus' slave revolt were crucified along the Appian Way in 71 BCE, demonstrating publicly what would happen to any other slave that attempted to revolt. It was also widely used against rebels in the provinces governed by Rome. Being one of the most rebellious provinces in the entire empire, Judea was the scene of thousands of crucifixions. As indicated above, when Herod died (4 BCE), a rebel named Judas led a revolt against Roman rule, which resulted in his crucifixion and that of 2,000 of his followers. In 6 CE, another Judas, Judas of Galilee, founded the Zealots and led a revolt against the imposition of direct Roman rule. This revolt was sparked by the Roman census of Judea conducted that year.

1 The exact fate of Judas and his followers is not known. However, Acts (5:36-37) states that, "like Theudas before him, Judas "also perished, and all who followed him were scattered." The mantle of Judas' leadership passed to his two sons, who were subsequently crucified in 46-48 CE. Judas' third son, Menahem, led the massive Jewish revolt against Rome that took place in 66 CE., which resulted in thousands of Jews being crucified. Eleazar, the rebel leader at Masada (where some 900 Jews died in 73 CE) was also a descendent of Judas. The Jews revolted one final time in 132-136 CE, this time under the leadership of the messianic prophet Simon ben Kosevah, (Bar Kokhba), with yet more crucifixions.

Because crucifixion was the principal method used for executing Jewish rebels by Roman authorities in Judea, Brandon (1967:145) claims, "The cross was the symbol of Zealot sacrifice before it was transformed into the sign of Christian Salvation." Given the political connotation associated with the cross, Jesus' statements --in Mark (8:34),

"If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me"; in Matthew (10:38), "whoever does not take up the cross and follow me is not worthy of me"; and in Luke (14:27), "Whoever does not carry the cross and follow me cannot be my disciple"-- may have had a very different meaning then than is attributed to them by Christians today.2

Marcus Antonius Felix, the Roman procurator of Judea (52-60 CE), captured another brigand chief named Eleazar (son of Deinaeus), who he sent him to Rome, along with several of his close associates. He then crucified many of his followers. According to Josephus (Jewish Wars 2: 253),

He [Felix] captured the chief brigand Eleazar who had carried out raids in the country for twenty years and many of those who were with him and sent them to Rome. The number was limitless of the brigands crucified by him and of the populace discovered to be in association with him whom he punished.

While crucifixion was practiced by many ancient societies, along with other brutal forms of execution, it was most widely practiced by the Romans. In his exhaustive study of different forms of execution in the ancient world, Samuelsson (2011: 29) defines crucifixion as

An attempted or completed execution by suspension, in which the victim is nailed or tied with his limbs to a vertical execution tool, usually a pole, with or without crossbeam, and thereby publicly displayed, in order to be subjected to an extended, painful death struggle.

Crucifixion, generally accompanied by scourging, was meant to be an extremely painful and humiliating form of execution. Nailing was frequently, though not always, used. However, when nailing was involved it could include nailing just the arms, letting the body dangle on the cross or pole. It could also involve the nailing of both arms and legs, and even skulls. Crucifixion victims did not die immediately, but generally died slowly, suffering several days of excruciating pain and asphyxiation before they died. It was meant to be an agonizing and demeaning form of execution in which the victim and the shame associated with his crime was placed on publicly display for everyone to see. Marcus Fabius Quintilian (c. 35-95 CE), a Roman consul under the emperor Vespasian, was quite explicit about its purpose.

Whenever we crucify the guilty, the most crowded roads are chosen, where the most people can see and be moved by this fear. For penalties relate not so much to retribution as to their exemplary effect. (Declamationes Minores, 274)

The Romans even constructed specific sites in various towns that were reserved for crucifixions. In Rome, the site was located just outside the Esquiline Gate on the eastern border of the city;

Golgotha was such a site in Jerusalem. Crucifixions were also occasionally performed as part of public entertainment. The following announcement for gladiatorial fights in Campania included a reference to crucifixions being performed.

At Cumae, 20 gladiatorial pairs and their substitutes will fight on 1 October, 5 October, 6 October, and 7 October. There will be cruciarii (individuals to be crucified), a fight with wild beasts and the velarium (awning) will be used [over the arena]. (Cook 2012: 71)

Crucifixion was also used as a military tactic. Josephus describes the Roman use of crucifixion on several occasions. At one point in his Jewish Wars (5.449-451) he described an incident in which Roman soldiers were given free rein in their crucifixion of Jews during the Jewish Revolt in 66-73 CE

They were first whipped, and then tormented with all sorts of tortures before they (Jewish resistors) died, and were then crucified before the wall of the city. This miserable procedure made Titus greatly to pity them, while they caught every day five hundred Jews; nay, some days they caught more: yet it did not appear to be safe for him to let those that were taken by force go their way, and to set a guard over so many he saw would be to make such as great deal them useless to him. The main reason why he did not forbid that cruelty was this, that he hoped the Jews might perhaps yield at that sight, out of fear lest they might themselves afterwards be liable to the same cruel treatment. So the soldiers, out of the wrath and hatred they bore the Jews, nailed those they caught, one after one way, and another after another, to the crosses, by way of jest, when their multitude was so great, that room was wanting for the crosses, and crosses wanting for the bodies.

Jesus lived during a period of heightened messianic fervor and of intense political activity against Roman rule that began long before Jesus' birth and lasted well after his death.

Josephus names five major Jewish military messiahs between 40 BCE and 73 CE. Horsley and Hanson (1985) list six bandit leaders, six messianic claimants and five prophets, not including Jesus, between 47 BCE and 135 CE.

Rosenblatt (1956: 315) expresses quite clearly the intensity of the religious-political divisions that existed in Palestine during the first century CE.

Sectarianism flourished, as it had never done before or after, in the little Jewish state on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean that had become a virtual Roman province, since the year 63 BCE. . . . The country was literally teeming with religious orders and brotherhoods, each with its own ritual, its special rules of purity and impurity and its distinctive interpretation of the Law. The three parties listed by Josephus - the Pharisees, Sadducees, and Essenes- apparently did not exhaust the actual number of sects in existence. There were many others besides, and even the former had their divisions and subdivisions.

Jesus and his followers would have been just another sectarian group competing for disciples.

The first century CE was, thus, a time intense religio-political turmoil throughout Palestine, much of which was a direct consequence of Roman colonization. Marvin Harris (1974) characterizes the intensity of the political opposition to Roman occupation.

From the gospels alone, you would never know that Jesus spent most of his life in the central theater of one of history's fiercest guerrilla uprisings. You could never guess that in 68 AD the Jews went on to stage a full-scale revolution that required the attention of six Roman legions . . . (about 36,000 soldiers) . . . under the command of two future Roman emperors before it was brought under control.

Jesus also lived in one of the provinces that served as a center of that revolt.

3 Given that the Zealots represented a violent political faction among the Jews of the first Century CE fighting to overthrow Roman rule, it is significant that one of Jesus' apostles, Simon, is referred to several times as "Simon the Zealot". (Mark 3:18; Matthew 10:4; Luke 6:15; Acts 1:13). Another radical group, known as the Sicari, existed at the same time as the Zealots. The name Sicari means "dagger men" and was derived from the word sica, the Latin term for a small dagger. The members of this group were called Sicari by the Romans because they used small daggers to assassinate prominent Jewish leaders (most notably Sadducees) who they believed had betrayed the Jewish people in order to maintain their positions of power in the community. It was the Sicari that led the resistance to Roman occupation at Masada. The name Sicari derives from the Latin, sicarius, which is remarkably close to Iscariot (simply invert the first two letters of the word sicarius and replace the Latin ending [us] with the Greek ending [ot] and you have Iscariot). John (13:2) states that Judas Iscariot was Simon the Zealot's son. If this is true, then Judas, like his father Simon, may also have been a Zealot. Significantly, at one point Judas criticizes Jesus for wasting money anointing himself with oil when the money in question could have been given to the poor (see John 12:5). This would have been precisely the kind of issue that would have concerned a Zealot.

The Two Thieves

All four gospels claim that Jesus was crucified between two "thieves", though their description of how these two men interacted with Jesus differs significantly. Again, as in the evolving characterization of Pilate, the description of the two thieves changes as we move through the gospels. Both Mark (15:27-32) and Mathew (27:38-44) have the two thieves deride Jesus along with the crowd of onlookers shouting taunts at him. (The similarity in the thieves' response in Mark ad Matthew should not be considered important, since nearly two-thirds of the gospel of Matthew is a direct word-for-word copy of the gospel of Mark.) With Luke, however, the story changes. In Luke's version, only one of the thieves joins in with the crowd deriding Jesus. The other thief does not. In responding to the first thief's taunts, the second thief says,

"Do you not fear God, since you are under the same sentence of condemnation? And we indeed have been condemned justly, for we are getting what we deserve for our deeds, but this man has done nothing wrong." (Luke 23:40-41). Then, according to Luke (23:42-43), the second thief says to Jesus, "Jesus, remember me when you come into[ your kingdom," and Jesus responds, "Truly I tell you, today you will be with me in Paradise." John (19:18) says nothing about the two thieves, except to mention them. Later, however, as the Jesus tradition grew and evolved, new items were added to the Jesus story. One of those items involved the two thieves. In the second-century Infancy Gospel of Thomas, as Jesus' family returned to Palestine following their flight to Egypt to avoid Herod's slaughter of children in Bethlehem, they passed through a country infested with robbers. There they encountered two thieves: Titus and Dumachus. According to this infancy narrative, Titus pleads with Dumachus to let the family proceed unharmed, but the latter refuses. In response to his kindness, Mary said to Titus, "The Lord will receive thee to his right hand, and grant thee pardon of thy sins" (8:5). The infant Jesus then proclaims, "When thirty years are expired, O mother, the Jews will crucify me at Jerusalem; and these two thieves shall be with me at the same time upon the cross. . . . and from that time Titus shall go before me into paradise" (8:6-7), thus adding a prediction made by Jesus in his infancy to a later event described in the gospel of Luke (23:39-43).

Significantly, the Latin term used to refer to these "thieves" was

lestai. This was the term the Romans used to refer to the Zealots. It more correctly means "brigands" or "terrorists" rather than thieves. In the Gospel of John (18:40), Barabbas, who was arrested for attacking the Roman garrison in Judea, is said to be a lestai. Barabbas' attack on the garrison may have occurred simultaneous with Jesus' attack on the Temple. Thus, the Romans executing Jesus may quite likely have simply seen themselves crucifying a group of rebels.

Jesus' Entrance into Jerusalem

The Romans' seditious view of Jesus was likely enhanced by two events described in the gospels. The first involved Jesus' riding into Jerusalem on a donkey. All four gospels --Mark (11:1-10) Matthew (21:1-11) Luke (19:28-38) and John (12:12-13)-- describe Jesus riding into Jerusalem on a donkey before a large crowd praising him as he rode.

Many people spread their cloaks on the road, while others spread branches they had cut in the fields. Those who went ahead and those who followed shouted,

"Hosanna!"

"Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!"

"Blessed is the coming kingdom of our father David!" (Mark 11:8-9)

. . . a very large crowd spread their cloaks on the road, while others cut branches from the trees and spread them on the road. The crowds that went ahead of him and those that followed shouted, "Hosanna to the Son of David!" (Matthew 21:8-9)

When he came near the place where the road goes down the Mount of Olives, the whole crowd of disciples began joyfully to praise God in loud voices for all the miracles they had seen:

"Blessed is the king who comes in the name of the Lord!" (Luke 19:37-38)

They took palm branches and went out to meet him, shouting, "Hosanna!" "Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!" "Blessed is the king of Israel!" (John 12:13)

Matthew (21:4-5) claims that this act was done

"to fulfill what was spoken through the prophet:"

Say to Daughter Zion,

"See, your king comes to you,

gentle and riding on a donkey,

and on a colt, the foal of a donkey."

In typical fashion, however, Matthew distorts Zechariah's original quote and takes it entirely out of its historical context in order to present the life and teaching of Jesus as fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy.

4 The quote that Matthew borrows (and distorts) comes from Zechariah (9:9)

Rejoice greatly, Daughter Zion!

Shout, Daughter Jerusalem!

See, your king comes to you,

righteous and victorious,

lowly and riding on a donkey,

on a colt, the foal of a donkey

By leaving out the complete quote, Matthew removes the clear political meaning of Zechariah's message. Zechariah was one of the 12 minor prophets who preached during the post-exilic period following the fall of Jerusalem in 586 BCE. Zechariah predicted that God would send a king to defeat Israel's enemies and restore it to its former position.

The Coming of Zion's King

Rejoice greatly, Daughter Zion!

Shout, Daughter Jerusalem!

See, your king comes to you,

righteous and victorious,

lowly and riding on a donkey,

on a colt, the foal of a donkey.

I will take away the chariots from Ephraim

and the warhorses from Jerusalem,

and the battle bow will be broken.

He will proclaim peace to the nations.

His rule will extend from sea to sea

and from the River to the ends of the earth.

As for you, because of the blood of my covenant with you,

I will free your prisoners from the waterless pit.

Return to your fortress, you prisoners of hope;

even now I announce that I will restore twice as much to you.

I will bend Judah as I bend my bow

and fill it with Ephraim.

I will rouse your sons, Zion,

against your sons, Greece,

and make you like a warrior's sword.

(Zechariah 9:9-13)

The political context of Zechariah's prophecy can be seen in the verses that precede those presented above. In the earlier verses, contained in a section titled

Judgment on Israel's Enemies, Zechariah (9:1-7) prophesized that God will reek his vengeance on Israel's enemies, naming specifically Tyre, Sidon, Ashkelon, Hamath, Damascus and Philistines, among others. The section concludes with the following verse (Zechariah 9:8), just before the verse expropriated by Matthew.

But I will encamp at my temple

to guard it against marauding forces.

Never again will an oppressor overrun my people,

for now I am keeping watch.

The means by which Jesus chose to enter Jerusalem, thus, had clear symbolic importance. It was an explicit reference to Zechariah's pronouncement of the coming King of Judea. This act would have conveyed a clear political message, which a Jewish audience --especially Jewish nationalists fighting Roman occupation-- would undoubtedly have recognized. It would, furthermore, have had unmistakable political implications by the very fact that it occurred in conjunction with the Jewish celebration of Passover, that is, as Jews were celebrating their escape from Egyptian slavery while suffering under Roman occupation. It is doubtful those present could have interpreted Jesus' entrance in any other way. Tabor (2006: 192-193) is quite explicit on this point.

By this provocative act of prophetic "pantomiming" Jesus was openly declaring himself claimant to the throne of Israel. No one who knew the Hebrew Prophets could have missed the point.

And the crowd's response also had overt political implications. Three of the four gospels present the crowd following Jesus all shouting

Hosanna! The Hebrew word, Hosanna, translates to mean, "Save", which had a political meaning to Jews at the time. The political implication of the cry is made clear by the reference to David, to the King of Israel, and to Jesus as his descendent in the various gospel accounts.

The crowds that went ahead of him and those that followed shouted, "Hosanna to the Son of David!" "Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!" "Hosanna in the highest heaven!" (Matthew 21:9)

Hosanna!

Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord!

Blessed is the coming kingdom of our

ancestor David!

Hosanna in the highest heaven! (Mark 11:9-10)

They took palm branches and went out to meet him, shouting, "Hosanna!" "Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!" "Blessed is the king of Israel!" (John 12:13)

The political implications of Jesus' chosen method for entering Jerusalem would not have escaped Pilate's attention either, as it would have represented a direct public challenge to Roman rule. Passover, as already indicated, was a highly charged event in Jerusalem. The population of the city swelled significantly due to thousands of migrants entering the city at this time, much as the population of Mecca swells each year as many thousands of pilgrims travel there each year on the Hajh. Due to the precarious situation that the Passover presented, it was the one time of the year that Pilate left his palace in Caesarea to reside in Jerusalem. He did so in order to keep a close eye on the situation there. He also stationed additional troops in Jerusalem at this time in order to maintain tighter control over an enlarged and potentially volatile Jewish population. If Jesus did ride into Jerusalem as the gospels describe, this would certainly have contributed to Pilate's treating Jesus as a political criminal. Indeed, he executed many others for engaging in far less provocative acts.

The Cleansing of the Temple

Jesus' triumphant entrance into Jerusalem was shortly followed by a second provocative act: his "cleansing of the Temple". This attack is described in all four gospels.

On reaching Jerusalem, Jesus entered the temple courts and began driving out those who were buying and selling there. He overturned the tables of the money changers and the benches of those selling doves, and would not allow anyone to carry merchandise through the temple courts. And as he taught them, he said, "Is it not written: ‘My house will be called a house of prayer for all nations’? But you have made it ‘a den of robbers.’" (Mark 11:15-17)

Jesus entered the temple courts and drove out all who were buying and selling there. He overturned the tables of the money changers and the benches of those selling doves.

"It is written," he said to them, "‘My house will be called a house of prayer,’ but you are making it ‘a den of robbers. (Matthew 21:12-13)

When Jesus entered the temple courts, he began to drive out those who were selling. "It is written," he said to them, "‘My house will be a house of prayer’; but you have made it ‘a den of robbers.’" (Luke 19:45-46)

5

When it was almost time for the Jewish Passover, Jesus went up to Jerusalem. In the temple courts he found people selling cattle, sheep and doves, and others sitting at tables exchanging money. So he made a whip out of cords, and drove all from the temple courts, both sheep and cattle; he scattered the coins of the money changers and overturned their tables. To those who sold doves he said, "Get these out of here! Stop turning my Father’s house into a market!" (John 2:13-16)6

_-_Christ_Cleansing_the_Temple_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

This incident constituted a violent

7 assault on the fundamental economy of the Temple and on the income and authority of the Temple hierarchy (the Sadducees). Jews were expected to make sacrifices to God in the Temple as part of their religious obligation. Many Jews traveled from distant lands for the explicit purpose of sacrificing to God in the Jerusalem Temple. The number of people coming to Jerusalem for that purpose was significantly increased during Passover. It was, of course, inconvenient --and in many cases impossible-- for pilgrims to bring with them the animals they intended to sacrifice. For this reason, the Temple authorities organized the Temple grounds so as to facilitate pilgrims performing their religious duties. They permitted merchants to sell sacrificial animals (doves, sheep and cattle) and authorized "money changers" to convert the various currencies that pilgrims brought with them into the Temple currency needed to perform sacrifices. Graven images were forbidden within the Temple walls; consequently, coins containing the likenesses of Roman emperors on them, who were considered deities, had to be exchanged for Temple currency. Thus, the very people that worshippers needed in order to perform their religious duties --money changers and individuals selling sacrificial animals-- were the "robbers" that Jesus attacked. This would have given Caiaphas, the high priest at the time, ample reason to report Jesus to Pilate.8

The Empty Tomb

Our knowledge of Roman policy and practice regarding crucifixion raises serious doubts about the gospel accounts of Jesus' followers discovering an empty tomb. Besides the fact that no two gospel accounts of the discovery of the empty tomb are the same, Bart Ehrman (2014) argues that it is highly questionable whether Jesus was even buried in a tomb from which his body could be found missing and, thus, claimed to have resurrected. As already indicated, the ultimate purpose of crucifixion was to torture and humiliate the criminal who was crucified in a highly public manner in order to dissuade anyone else from committing a similar crime. Part of that humiliation was leaving the body of the crucified victim on the cross after death to decompose and be consumed by birds of prey. According to Martin Hengel (1977: 87), "Crucifixion was aggravated further by the fact that quite often its victims were never buried. It was a stereotyped picture that the crucified victim served as food for wild beasts and birds of prey. In this way, his humiliation was made complete." Cook (2011: 209) adds,

some crucified bodies were simply abandoned on the cross. . . . in Roman (and presumably Greek) practice the bodies of some crucified individuals were left to decompose on the cross. The picture is horrifying, but undoubtedly the necrotic flesh rotted away, and what was not eaten by birds of prey fell to the ground and was occasionally consumed by dogs.

One of the clearest statements about Roman refusal to bury corpses of executed individuals comes from Eusebius, who described the persecutions at Lyons during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161-180 CE). According to Eusebius (

Ecclesiastical History 5.1.61-62), the bodies of crucified Christian martyrs were left on public view for six days, after which they were burned and their ashes thrown into the Rhone River (Cook 2011: 196). Cook (2008: 281) notes elsewhere that "the birds of prey may have had their fill of the carcass before the hook was brought in" to drag the body to the grave. Juvenal (55-140 CE) comments in his Satires (14.77-78), vultur iumento canibus cruci busque relictis I ad fetus properat partemque cadaveris adfert ("the vulture hurries to its young from beasts of burden, dogs, and abandoned crosses and brings some of the cadaver"). Petronius (27-66 CE), in his Satyricon (58.2) referred to a crucified boy lover named Giton, who was reviled as crucis offia, corvo rum cibaria ("cross meat, ravens food"). As Jean-Jacques Aubert (2002: 130) points out, one would not want to see hanging crucified corpses, "except for the sake of example."

By the same token, punishment and humiliation did not end with death on the cross; it continued even after the body was removed from the cross. What normally happened was that the criminal's body was tossed unceremoniously into a common grave containing the bodies of other criminals where it could be further degraded by scavenging animals. As Ehrman (2014: 156-161) points out, if Jesus was treated in the same manner as other crucifixion victims, he would not have been buried in a tomb where his body could be discovered missing. In fact, there would have been no reason for women to go to the tomb to anoint his body, as there would be no body to anoint.

Mark (15:43) gets around this issue by claiming that Joseph of Arimathea,

"a respected member of the council", went to Pilate to ask for Jesus' body. Matthew (27:57-58) repeats the same story, but refers to Joseph as a "rich man". Luke continues the story, claiming that Joseph was a "good and righteous man" who, while a member of the council, "had not agreed to their plan and action." John (19:38-39) elaborates on the story further, stating that "Joseph of Arimathea, who was a disciple of Jesus, though a secret one because of his fear of the Jews,9 asked Pilate to let him take away the body of Jesus." He adds that Nicodemus also came along, "bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes, weighing about a hundred pounds." Acts modifies the story even further. In Acts (13:28-29), it is the very same council that condemned Jesus to death that took him down from the cross and buried him in a tomb. Significantly, Paul, the earliest Christian writer, writing a full 20 years before the first gospel was written, says nothing about Joseph of Arimathea or of the discovery of an empty tomb. He merely states that "he was buried" (1 Corinthians 15:4). Again, as with other stories in the New Testament, with each retelling of the story of Jesus' crucifixion, new details are added to enhance Jesus' divinity. (cf. Abruzzi, The Birth of Jesus)

Ehrman raises several problems with the New Testament accounts of Jesus' death and argues that there are numerous reasons for doubting both the Joseph of Arimathea story and the discovery of an empty tomb. He begins by noting that the existence of a tomb is crucial to the resurrection story; "If there were no tomb for Jesus, or if no one knew where the tomb was, the bodily resurrection could not be proclaimed. You have to have a known tomb" (Ehrman 2014: 152). Consequently, a tomb story needed to be created. The first objection, of course, is that given what has been described above regarding Roman crucifixion, it is highly unlikely that Jesus' body would have ended up anywhere other than a common grave reserved for criminals. The Romans would not have cared in the least about Jewish burial customs, and given what is known about Pontius Pilate, he was perhaps the last person to show mercy and kindness to the followers of a criminal found guilty of sedition. He had already demonstrated on several occasions that he had no respect for Jewish sensitivities. It is, thus, highly unlikely that he would have given Joseph of Arimathea permission to treat Jesus' body differently from those of other criminals. There is also the additional problem that Mark (15:55,64) himself states quite explicitly that "the chief priests and the whole council were looking for testimony against Jesus to put him to death" and that "All of them condemned him as deserving death." It is strange that Joseph would condemn Jesus to death one day and go out of his way to arrange a decent burial for him the next day. Luke says that Joseph did not agree with the council's decision to condemn Jesus to death, but this directly contradicts Mark, who states that the condemnation was unanimous. John tries to explain the problem away by saying that Joseph condemned Jesus to death because he was afraid of the Jews. This, of course, is in line with the increasing condemnation of the Jews for Jesus' crucifixion. It also contradicts Luke's statement that Joseph was a "good and righteous man." It doesn't seem reasonable that a "good and righteous man" would condemn another man to death whom he believes is innocent. Similarly, Joseph of Arimathea could hardly be considered a "good and righteous man" who condemned Jesus to death if, according to John, he was a disciple of Jesus. If this were the case, he clearly would not have stood up for the principles he believed, a rather dubious definition of being "good and righteous".

There is also the problem of the variant and contradictory stories told about the discovery of the empty tomb in the different gospels and what occurred afterwards. According to Mark (16:1), "Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of James, and Salome" went to the tomb. As they approached the tomb,

they asked each other, "Who will roll the stone away from the entrance of the tomb?" But when they looked up, they saw that the stone, which was very large, had been rolled away. As they entered the tomb, they saw a young man dressed in a white robe sitting on the right side, and they were alarmed. "Don’t be alarmed," he said. "You are looking for Jesus the Nazarene, who was crucified. He has risen! He is not here. See the place where they laid him. But go, tell his disciples and Peter, ‘He is going ahead of you into Galilee. There you will see him, just as he told you.’" Trembling and bewildered, the women went out and fled from the tomb. They said nothing to anyone, because they were afraid. (Mark 16:2-8)

According to

Matthew (28:1), it is "Mary Magdalene and the other Mary" who go to the tomb. However, in Matthew's account,

There was a violent earthquake, for an angel of the Lord came down from heaven and, going to the tomb, rolled back the stone and sat on it. His appearance was like lightning, and his clothes were white as snow. The guards were so afraid of him that they shook and became like dead men. The angel said to the women, "Do not be afraid, for I know that you are looking for Jesus, who was crucified. He is not here; he has risen, just as he said. So the women hurried away from the tomb, afraid yet filled with joy, and ran to tell his disciples. Suddenly Jesus met them. "Greetings," he said. They came to him, clasped his feet and worshiped him. Then Jesus said to them, "Do not be afraid. Go and tell my brothers to go to Galilee; there they will see me. (Matthew 28:2-10)

Luke provides yet another description of who went to the tomb and what happened when they arrived there. In Luke's account, "two women" (unnamed) went to the tomb, and the events that transpired there were substantially different from those described by either Mark or Matthew.

On the first day of the week, very early in the morning, the women took the spices they had prepared and went to the tomb.

They found the stone rolled away from the tomb, but when they entered, they did not find the body of the Lord Jesus. While they were wondering about this, suddenly two men in clothes that gleamed like lightning stood beside them. In their fright the women bowed down with their faces to the ground, but the men said to them, "Why do you look for the living among the dead? He is not here; he has risen! Remember how he told you, while he was still with you in Galilee: ‘The Son of Man must be delivered over to the hands of sinners, be crucified and on the third day be raised again.’ " Then they remembered his words. When they came back from the tomb, they told all these things to the Eleven and to all the others. It was Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the others with them who told this to the apostles. But they did not believe the women, because their words seemed to them like nonsense. (Luke 24:1-11)

John's version of the discovery of an empty tomb differs sharply from the three previous accounts. While John names only Mary Magdalene as the initial person to visit the tomb, his description of what happened upon her discovery adds material not contained in any of the earlier accounts.

Early on the first day of the week, while it was still dark, Mary Magdalene went to the tomb and saw that the stone had been removed from the entrance. So she came running to Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one Jesus loved, and said, "They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we don’t know where they have put him!" So Peter and the other disciple started for the tomb. Both were running, but the other disciple outran Peter and reached the tomb first. He bent over and looked in at the strips of linen lying there but did not go in. Then Simon Peter came along behind him and went straight into the tomb. He saw the strips of linen lying there, as well as the cloth that had been wrapped around Jesus’ head. The cloth was still lying in its place, separate from the linen. Finally the other disciple, who had reached the tomb first, also went inside. He saw and believed. (John 20:1-8)

Given the variation that occurs in each evangelist's description of the circumstances surrounding the discovery of Jesus' empty tomb, none of them can be considered credible. The same can be said regarding the appearances made by Jesus following his purported resurrection. According to Mark (16:9-11),

When Jesus rose early on the first day of the week, he appeared first to Mary Magdalene, out of whom he had driven seven demons. She went and told those who had been with him and who were mourning and weeping. When they heard that Jesus was alive and that she had seen him, they did not believe it.

In Mark (16:15), Jesus later appeared to the apostles, chastised them for not believing Mary Magdalene and then instructed them to "Go into all the world and preach the gospel to all creation." Unfortunately, however, Mark's account of Mary Magdalene telling the apostles of the empty tomb in verse 16:10 directly contradicts his statement in verse 16:8 that "trembling and bewildered, the women went out and fled from the tomb. They said nothing to anyone, because they were afraid." This contradiction derives from the fact that verses 16:9-20 are known to be forgeries added to the gospel centuries later by zealous scribes (see Holmes 2001; Tabor 2013: 230-231, 340, notes 12 and 13). Furthermore, not only are there multiple endings found in extant copies of Mark's gospel, but the added verses beyond Mark 16:8 are consistently absent from the earliest manuscripts, including the two oldest manuscripts, Sinaiticus and Vaticanus (ibid.: 340, note 12). They are also absent from some 100 Armenian manuscripts, as well as the Old Latin and the Sinaitic Syrian manuscripts (ibid.).

Furthermore, not only is, the writing style of the added material distinct from that of the rest of Mark's gospel, but both Clement of Alexandria and Origen (two 3rd-century Christian scholars) display no knowledge of the added ending (Tabor 2013: 231). In addition, Eusebius and Jerome (two 4th-century Christian writers) knew of its existence, but stated that nearly all Greek manuscripts they knew of didn't include it (ibid.) As Tabor (2013: 231) points out, the added text of Mark is nothing more than "a clumsy composite of the sightings of Jesus reported by Matthew, Luke and John" containing "no independent material that can be identified as specifically from Mark." Thus, there are no post-resurrection appearances made by Jesus in Mark; the gospel simply ends with the two women fleeing the tomb and telling no one of their discovery. With the removal of this inserted material, the ending of Mark's gospel is consistent with the theme reiterated throughout the first gospel that no one, not even Jesus' own apostles, truly understood him or his mission.

Matthew's gospel also contains a post-resurrection contradiction. According to Matthew (28:7), the angel at the tomb told the two women to "tell his disciples: ‘He has risen from the dead and is going ahead of you into Galilee. There you will see him.’" So, they ran from the tomb to tell the apostles what they were told. On the way, Jesus met them and confirmed the message from the angel, telling them, "Do not be afraid. Go and tell my brothers to go to Galilee; there they will see me." (Matthew 28:10) According to Matthew (28:16), "Then the eleven disciples went to Galilee, to the mountain where Jesus had told them to go," and there Jesus commanded them "to go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit." This ending of Matthew poses serious problems. Throughout Matthew's gospel, Jesus makes it quite explicit that he has come for the redemption of Jews and Jews alone. On several occasions he presents Gentiles in a negative light (cf. Matthew 10:17, 20:19 and 20:25). On one occasion, he is quite explicit about his mission, instructing his apostles, "Do not go among the Gentiles or enter any town of the Samaritans. Go rather to the lost sheep of Israel. (Matthew 10:5-6). Following the Sermon on the Mount, he again reiterates the Jewish orientation of his mission.

Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them. For truly I tell you, until heaven and earth disappear, not the smallest letter, not the least stroke of a pen, will by any means disappear from the Law until everything is accomplished. (Matthew 15:17-18)

Jesus preaches only among Jews in Matthew (as well as in Mark) and at one point (Matthew 19:28) tells his apostles, "Truly I tell you, at the renewal of all things, when the Son of Man sits on his glorious throne, you who have followed me will also sit on twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel, a clear expression of the exclusive Jewish focus of his mission. Finally, Jesus goes so far as to refuse to cure the daughter of a woman because she is a Gentile (Matthew 15:21-28), telling his apostles, "I was sent only to the lost sheep of Israel." (Matthew 15-24). When the woman beseeches him, crying "Lord, help me!", he responds, "It is not right to take the children’s bread and toss it to the dogs" (the dog being a derogatory term used by Jews at the time to refer to Gentiles). He only concedes to cure the woman's dying daughter after she demeans herself and replies, "Yes it is, Lord. Even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their master’s table." So, it seems hardly likely that Jesus, who recruited only Jewish apostles, preached exclusively among Jews, claimed that he was sent only to save Jews, expressed his teaching in Jewish terms, instructed his apostles while he was living not to preach among the Gentiles and went so far as to refuse to cure a desperate woman's daughter because she was not Jewish, would upon his resurrection tell his apostles to preach among "all nations . . . in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit", especially since the concept of the trinity did not become a part of Christian teaching until long after Jesus' death.

Luke's account of Jesus' post-resurrection appearances also cannot be trusted. In Chapter 24, following several appearances, Luke clearly implies that Jesus ascended into heaven on the very day of his resurrection. However, in the opening verses of Acts (1:3) (written by the same author), he directly contradicts himself by stating explicitly that the ascension occurred 40 days later.10

In the first book, O Theoph′ilus, I have dealt with all that Jesus began to do and teach, until the day when he was taken up, after he had given commandment through the Holy Spirit to the apostles whom he had chosen. To them he presented himself alive after his passion by many proofs, appearing to them during forty days, and speaking of the kingdom of God. (Acts 1:1-3)

As I have shown elsewhere (Abruzzi, When Was Jesus Born?), Luke was not a reliable historian. His descriptions of historical events cannot be trusted, because he regularly manipulated the facts to fit his desired narrative. Many of his descriptions of Paul's travels and missionary work, for example, directly contradict Paul's own accounts, so much so that in an extensive comparison of Paul's letters with Luke's description of the same events in Acts (cf. Acts 9:19-29 vs. Galatians 1:16-17), Dougherty (1997: 54) describes Luke's writing as "Apologetic Historicizing." Similarly, Luke's description of the events surrounding Jesus' birth is pure fantasy, as is his account of Jesus crucifixion and post-resurrection appearances.

John's gospel also has problems related to Jesus' post-resurrection appearances, in addition to those already mentioned. The entire Chapter 21 is considered by most biblical scholars to have been added later by Christian scribes and is generally viewed, like Mark (16:9-20), as an awkward addition inconsistent with the concluding verses of chapter 20.11

Jesus performed many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not recorded in this book. But these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name. (John 20:30-31)

Given, then: (1) the discrepancies among the various gospels regarding the discovery of the empty tomb and the events that transpired afterwards; (2) the forgery distorting Mark's description of what occurred; (3) the contradiction in Matthew's gospel between the message proclaimed by Jesus after his death and that presented quite frequently while he was still alive; (4) the general unreliability of Luke and his tendency to make up facts as he needs them; (5) the addition of a whole chapter added at the end of John's gospel; (6) the importance of the existence of an empty tomb story to support a resurrection narrative; (7) the contradictions associated with the gospel accounts of Joseph of Arimathea; and (8) our knowledge of Roman policy and practice with regard to crucified criminals, none of the post-crucifixion narratives can be given any historical credibility.12

Roman Attitude Towards a Crucified Deity

Jesus' crucifixion represented a serious obstacle to the early expansion of Christianity within the Roman Empire. Given the fact of Jesus' crucifixion, the reasons for his being crucified and the contempt that Romans had for those who were crucified, Jesus' crucifixion posed a serious problem for early Christians promoting their new religion in the larger Greco-Roman world. Several ancient sources expressed contempt for Christians and Christianity in Rome and elsewhere in the empire during the early centuries of the Common Era. The Roman Senator and historian, Publius Cornelius Tacitus. (116-117 CE), for example, refers to Christians in his Annals (15:44) while discussing Nero's burning of Rome in 64 CE. According to Tacitus, in an effort to counteract accusations that he himself had initiated the fire, Nero blamed the conflagration on Christians.

Hence to suppress the rumor, he falsely charged with the guilt, and punished Christians, who were hated for their enormities. Christus, the founder of the name, was put to death by Pontius Pilate, procurator of Judea in the reign of Tiberius: but the pernicious superstition, repressed for a time broke out again, not only through Judea, where the mischief originated, but through the city of Rome also, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their center and become popular.

Much of the pagan world's hostility to Christianity focused on what would have been considered to most Romans as an absurd belief: that the Son of God was crucified as a common criminal. Such a belief stood in sharp contrast to the prevailing Hellenistic beliefs in the immortality of supernatural beings. Jesus' crucifixion was, thus, a major embarrassment for early Christians. In all the other religions, gods were supreme beings who would not have suffered such ignominy. Indeed, Justin (St. Justin Martyr) stated very clearly that non-Christians believed Christians were mad to put forth a crucified savior.

They say that our "madness" consists in the fact that we put a "crucified man" in second place after the unchangeable and eternal God, the Creator of the world. (Justin, First Apology 13)

Hengel (1987: 6-7)

reinforces the problem that Jesus' crucifixion presented for early Christians attempting to proselytize their religion in the larger Hellenistic world.to believe that the one pre-existent Son of the one true God, the mediator at creation and the redeemer of the world, had appeared in very recent times in out-of-the-way Galilee as a member of the obscure people of the Jews, and even worse, had died the death of a common criminal on the cross, could only be regarded as madness. The real gods of Greece and Rome could be distinguished from mortal men by the very fact that they were immortal -they had absolutely nothing in common with the sign of the cross as a sign of shame.

Even Deuteronomy in the Hebrew Bible expressed a curse upon anyone "hanged on a tree."

And if a man has committed a crime punishable by death and he is put to death, and you hang him on a tree, his body shall not remain all night upon the tree, but you shall bury him the same day, for a hanged man is accursed by God; you shall not defile your land which the Lord your God gives you for an inheritance. (Deuteronomy 21 :22-23)

Hengel (1987: 83)

concludes one of his chapters with the following statement.When Paul spoke in his mission preaching about the 'crucified Christ' (Corinthians 1 :23; 2:2; Galatians 3:1 ), every listener in the Greek-speaking East between Jerusalem and Illyria (Romans 15: 19) knew that this Christ had suffered a particularly cruel and shameful death, which as a rule was reserved for hardened criminals, rebellious slaves and rebels against the Roman state. That this crucified Jew, Jesus Christ, could truly be a divine being sent on earth, God's son, the Lord of all and the coming judge of the world, must inevitably have been thought by any educated man to be utter 'madness' and presumptuousness.

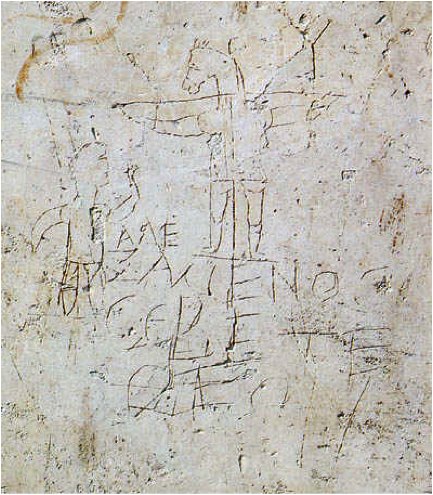

One interesting expression of Roman hostility towards Christianity as a religion worshiping a crucified criminal can be found in graffiti scratched onto one of the walls of the

paedagogium, the imperial training school for slaves near the Palatine Hill in Rome (see Cook 2008: 282-285). Known as the Palatine Graffito, the image can be dated to the early second century CE, making it perhaps the earliest known depiction of Christ, though not a complimentary one. The drawing shows a donkey-headed man crucified on a cross. Standing to the left of the donkey is a man with his arm raised (throwing a kiss), who is presumably Alexemanos, the butt of the joke. The caption accompanying the text reads, Alexamenos sebete theon ("Alexamenos worships his god").

As the above comments make clear, the dishonor associated with crucifixion was a major obstacle to early Christian proselytizing. Christians promoting Jesus as the Son of God in the Hellenistic world would have been comparable to someone today proclaiming that a criminal executed in the U.S. --a punishment reserved for the most extreme forms of criminal behavior-- was the Son of God. Gradually, however, Christianity, particularly the Church in Rome, became increasingly aligned with imperial rule and was eventually declared the official religion of the Roman Empire in 389 CE by the Emperor Theodosius. In the process, Christian theology changed as the human Jesus became increasingly viewed as the spiritual Christ, and the crucifixion was transformed from a criminal penance into an event of profound eschatological significance. With the power of Rome behind it, the Roman Church was able to eliminate competing interpretations of Jesus' crucifixion, including those presented by competing Christian sects.

13

NOTES

1. This is the census mentioned in Luke (2:1 ). However, the actual census occurred only in Judea and Samaria, not Galilee, and was undertaken at least 10 years after Herod died, meaning: (1) there was no reason for Joseph and his family to travel to Bethlehem for the census, and (2) Jesus could not have been born both during the census in 6 CE and during the reign of Herod, who died in 4 BCE. (see Abruzzi, When Was Jesus Born?)

2. Jesus was quite strict about what individuals must do to be one of his followers, even to the point of requiring his followers, as he had done, to abandon their family obligations. One example is shown in Jesus' recruiting James and John, the sons of Zebedee.

As he went a little farther, he saw James son of Zebedee and his brother John, who were in their boat mending the nets. Immediately he called them; and they left their father Zebedee in the boat with the hired men, and followed him. (Mk 1.19-20)

Luke (9:59-62) describes an instance in which two different men tell Jesus that they want to follow him, but must undertake certain family responsibilities first. Jesus makes it very clear that they must put their obligation to him above those to their families. (see also Matthew 8:21-22).

He said to another man, "Follow me."

But he replied, "Lord, first let me go and bury my father."

Jesus said to him, "Let the dead bury their own dead, but you go and proclaim the kingdom of God."

Still another said, "I will follow you, Lord; but first let me go back and say goodbye to my family."

Jesus replied, "No one who puts a hand to the plow and looks back is fit for service in the kingdom of God."

For a son to abandon the filial responsibility of burying his father in a kinship-based society would have been an incredibly egregious sign of disrespect and a serious violation of fundamental codes of family honor.

Jesus expressed the priority of loyalty to him and his mission over that towards family on another occasion as well. At one point, when Jesus' family was concerned about his preaching, they came to collect him, believing

"he is out of his mind" (Mark 3:20). When those with Jesus told him, "Your mother and brothers are outside looking for you," Jesus replied,

"Who are my mother and my brothers?" he asked.

Then he looked at those seated in a circle around him and said, "Here are my mother and my brothers! Whoever does God’s will is my brother and sister and mother." (Mark 3:33-35; see also Matthew 12:46-50)

3.

When Varus crucified 2,000 Jews who revolted following the death of Herod, according to Josephus (Antiquities 17. 289-296), he also destroyed the city of Sepphoris, burning it to the ground and turning its inhabitants into slaves, Sepphoris was only 4 miles from Nazareth. Sepphoris was rebuilt by Herod Antipas as a Roman town and became a prosperous community that Josephus described as the jewel of Galilee (Antiquities 18.27). Quite likely, Jesus and other men in Nazareth would have sought employment in Sepphoris.Consequently, while Jesus was only a young child when Sepphoris was brutally destroyed, the memory of the suffering inflicted on the Jewish population of the town likely had a significant effect on him and on his attitude towards Rome. Significantly, neither Sepphoris nor Tiberius are mentioned in the Gospels. Given that Jesus' mission was exclusively to Jews (Matthew 10:6, 15:24), he would not likely have preached there.

4.

Matthew is well known for the repeated distortion of Old Testament quotes in an effort to present Jesus as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy (see Abruzzi, When Was Jesus Born?, note 19.)

5. The references to "a house of prayer for all nations" and making the Temple a "den of robbers" in all three Synoptic Gospels (Mark, Matthew and Luke) is taken directly from Isaiah (56:7) and Jeremiah (7:11) respectively.

6. Whereas the three Synoptic gospels place Jesus' cleansing of the Temple at the end of his 6-month ministry, John places the event at the beginning of Jesus' 3-year ministry. John also differs from the other three gospels in having Jesus visit Jerusalem twice, once at the beginning and once at the end of his ministry.

7. It should be noted that the Temple disturbance was not the only evidence of violence associated with Jesus and his apostles. Indeed, at least five of Jesus' apostles displayed a propensity towards violence. As already indicated, Simon was a Zealot and Judas was likely a Sicari and/or a Zealot. Simon Peter used a sword to cut off a soldier's ear in the Garden of Gethsemane (Mark 14:47; Matt 26:51; Luke 22:50; John 18:10). In addition, both James and John, the sons of Zebedee, were known as the Sons of Thunder (Mark 3:17) because of their violent tempers. At one point they wanted to destroy a Samaritan village because its residents refused to allow Jesus to enter their village (Luke 9:54). Finally, anticipating his arrest on the Mount of Olives, Jesus instructed his apostles to carry swords (Luke 22: 35-38).

The inclusion of incidents involving violence is significant. One of the principles used in historical biblical criticism to evaluate the credibility of specific stories iin the gospels (and elsewhere in the bible) is the extent to which those stories contradict Christian beliefs about Jesus and could possibly have been added by later authors. Stories that include miraculous events associated with Jesus' actions, such as raising people from the dead. would fall into this category. By contrast, it is highly unlikely that Christians would have added stories linking Jesus and his followers with acts of violence. Such stories, therefore, contain greater credibility.

8. Caiaphas worked closely with Pilate. So well did they collaborate that, while Roman governors usually appointed a new high priest shortly after they took office, Pilate left Caiaphas continue as high priest throughout his entire ten-year procuratorship of Judea.

9. In John's gospel, the term "Jews" is used over three dozen times, referring repeatedly to Jews in the third person, even though Jesus and his apostles were all Jewish. The significance of this gospel's use of the term this way was to present the Jewish population as distinct from Jesus and his apostles. This reflects the fact that that John's gospel was written later than the other gospels, at a time when the nascent Christian community was composed mostly of gentiles (non-Jews). As Wassen and Hägerland (2021: 2) point out,

Jesus can hardly

have said, ‘Is it not written in your law …’ as he does when debating with other

Jews in John (Jn 10.34), for it was his law too; he was, of course, Jewish

himself. The phrase ‘your law’ reflects a time when, by contrast, most

Christ-believers were gentiles. For them it was natural that Moses's law was the

law of other people, not of Jesus himself.

The term "Jews" is also generally used by John to insinuate a collective negative attitude and behavior towards Jesus by this group, contributing to the increasing demonization of the Jewish population by the dominant gentile Christian community, which was disassociating Christianity from its Jewish origins. This increasing hostility towards the Jewish population was later to result in nearly two thousand years of anti-Jewish persecution and pogroms, culminating in the Nazi Holocaust of the mid-20th century (see Abruzzi, Christian Origins of the Holocaust).

10.

Haenchen (1966: 260) raises an interesting question, if one accepts the opening verses of Acts as historically correct.

If anyone takes the words of 1:3 seriously as history -that Jesus talked about the kingdom of God with his disciples for forty days- he either makes Jesus a preposterously poor teacher who cannot clarify what he means in ever so long a period, or he makes the disciples appear incredibly foolish.

11.

John (1:1-18), referred to as the Prologue, is also accepted by scholars as a later addition to that gospel. Its style and cadence suggest that it was a hymn included as part of early Christian worship.

12. To add to the contradictions already presented (and to which many more can be added), it is worth noting that in the gospels of Mark and Matthew, Jesus' post-resurrection appearances to his apostles occurred in Galilee, whereas in Luke and John they took place in Jerusalem.

13. Christians very quickly divided into a number of separate competing denominations professing distinct and conflicting theologies and Christologies. Among them were the Ebionites, Gnostics, Nazarenes, Marcionites, Docetists and Adoptionists, all of which were (and still are) declared heretics by the Roman Church (see Bauer 1934; Pagels 1979; Beskow 1983; Ehrman 2003; Jenkins 2008; MacCulloch 2009). Despite the Roman Church's doctrine that it represents the continuous true line of succession from Jesus and his apostles --the principle of the Apostolic Succession-- from which all other Christian variants deviated, Walter Bauer (1934) has shown quite convincingly that in every territory he examined within the Roman Empire, the so-called "heretical" forms of Christianity pre-existed that of the mainstream church. They were subsequebtly replaced and their religious literature destroyed, often forcibly, once the Roman Church became the official Imperial Church with the power of the Empire behind it. At the same time, a frequently violent conflict, resulting in thousands of deaths, raged between Monophysites and Miaphysites within the Church over whether Jesus had a single divine nature or two distinct natures: human and divine.

Many of the beliefs that prevailed among early Christian communities exceeded the range of beliefs that exist among Christians today (see Abruzzi, The Birth of Jesus). The consolidation of beliefs into a single Christianity was largely the result of the eventual dominance of what has become known as the "Orthodox" faction within the early Church, centered in Rome, supported by Roman Emperors and eventually declared the official religion of the Empire. With the consolidation of Orthodox dominance, most of the competing forms of Christianity were declared heretical, with their books burned and their adherents persecuted (see Bauer 1934; Pagels 1979; Ehrman 2003; Jenkins 2008, 2010; MacCulloch 2009). It is only as a result of recent archaeological discoveries, such as those at Nag Hammadi in Egypt in 1945, that the writings of these "Lost Christianities" have been discovered. So far, at least 40 gospels are known to have existed, only four of which were included within the New Testament by the Roman Church.

REFERENCES CITED

Aubert, Jean Jacques. (2002). A Double Standard in Roman Criminal Law? The Death Penalty and Social Structure in Late Republican and Early Imperial Rome, In J.-J. Aubert and B. Sirks, eds.,

Speculum Iuris: Roman Law as a Reflection of Social and Economic Life in Antiquity. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 94-133.Bauer, W. (1934). Orthodoxy & Heresy in Earliest Christianity (P. S. o. C. Origins, Trans.). Mifflintown, PA: Sigler Press.

Beskov, P. (1983). Strange Tales about Jesus: A Survey of Unfamiliar Gospels. Philadelphia: Fortress Press.

Brandon, S.G.F. (1967).

Jesus and the Zealots: The Study of the Political Factor in Primitive Christianity. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.Cook, John Granger. (2008). Envisioning Crucifixion: Light from Several Inscriptions and the Palatine Graffito.

Novum Testamentum 50(3): 262-285._____. (2011). Crucifixion and Burial.

New Testament Studies 57(2): 193-213._____. (2012). Crucifixion as Spectacle in Roman Campania.

Novum Testamentum 54(1): 68-100._____. (2014).

Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World: Scientific Investigations into the New Testament. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.Dougherty, D. J. (1997). Luke's Story of Paul in Corinth: Fictional History in Acts 18. Journal of Higher Criticism 4(1): 3-54.

Ehrman, Bart D. (2003). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

_____. (2014).

How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee. New York: Harper Collins.Harris, Marvin. (1974). Secret of the Prince of Peace. In Marvin Harris,

Cows, Pigs Wars and Witches: The Riddles of Culture. New York: Random House.Haenchen, E. (1966). The Book of Acts as Source Material for the History of Early Christianity. Studies in Luke-Acts. In L. E. Keck & J. L. Martyn (eds.), Studies in Luke-Acts. Nashville: Abingdon Press, pp. 258-278.

Hengel, Martin. (1977).

Crucifixion in the Ancient World and the Folly of the Message of the Cross, Philadelphia: Fortress Press.Holmes, M. W. (2001). To Be Continued . . . .The Many Endings of the Gospel of Mark. Bible Review 17(4): 12-23, 48-50.

Horsley, Richard A. and John S. Hanson. (1985).

Bandits, Prophets, and Messiahs: Popular Movements in the Time of Jesus. San Francisco: Harper & Row.Jenkins, P. (2008). The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa and Asia --and How It Died. New York: Harper Collins.

Jenkins, P. (2010). Jesus Wars: How Four Patriarchs, Three Queens, and Two Emperors Decided What Christians Would Believe for the Next 1,500 Years. New York: Harper Collins.

Jensen, Robin N. (2003). How Pilate Became a Saint.

Bible Review 19(6): 22-31, 47.MacCulloch, D. (2009). Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years. London: Penguin Books.

Notley, R. Steven. (2017). Pontius Pilate: Sadist or Saint?

Biblical Archaeology Review 43(4): 41-49, 59-60.Pagels, Elaine. (1979). The Gnostic Gospels. New York: Random House.

Polonen, Jane. (2004). Plebeians and Repression of Crime in the Roman Empire- From Torture of Convicts to Torture of Suspects. Revue Internationale des droits de l’Antiquité 51: 217-257.

Rosenblatt, Samuel. (1956). The Crucifixion of Jesus from the Standpoint of Pharisaic Law.

Journal of Biblical Literature 75(4): 315-321.Samuelsson, Gunnar. (2011).

Crucifixion in Antiquity: An Inquiry into the Background and Significance of the New Testament Terminology of Crucifixion. Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck.Schweitzer, Albert. (1910). The Quest for the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of Its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede. (English translation by William Montgomery). Augsburg: Fortress Publishers. (Geschichte der Leben-Jesu-Forschung, original German edition, 1906).

Tabor, James. (2006).

The Jesus Dynasty: The Hidden History of Jesus, His Royal Family, and the Birth of Christianity. New York: Simon & Schuster.Wassen, Celia and Tobias Hägerland. (2021). Jesus the Apocalyptic Prophet. London: t&t clark.

Winter, Paul. (1974). On the Trial of Jesus. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

* * * * *

Of Related Interest:

|

|

|

.jpg)

|

|

|

|

Christian Origins of the Holocaust

|

Hero and Inspiration to the Nazis

|

|

Christ in the Mystic Winepress

|

|

|

|

Bill O'Reilly is Killing Jesus

* * * * *