Conspiracy

Theories

That's what

they want you to believe

Dec 19th

2002

The Economist

|

Conspiracy

Theories Dec 19th

2002

|

|

Why are conspiracy

theories so popular?

WHO crashed those planes into the World Trade Centre? Israel, obviously. Mossad must have known that their country would profit from a surge in American hostility towards the Arabs, who were set up to take the rap. Shortly after September 11th 2001, the consensus on the Arab street was that only the Israeli secret service could have managed such deadly precision. Corroboration was quickly found in a report that 4,000 Jews who worked in the twin towers had been secretly warned to stay away that day.*

This was not the only interesting theory bandied around the souks. The doyen of Egyptian pundits, Hassanein Heikal, blamed the Serbs, noting that they were mad about losing Kosovo. Others fingered home-grown, Oklahoma-style extremists, or a plot by America's military-industrial complex, ever hungry for new enemies to boost defence budgets.

One fellow in a Cairo café told The Economist that the culprit was clearly not al-Qaeda, but rather something called al-Gur. Was this, perhaps, a terror network still more murderous than the Bin Laden gang? No. On closer listening, it transpired that the evil al-Gur was bent on avenging not some wicked Yankee geo-blunder, but the theft of the 2000 American presidential election. “It's obvious,” declared the café sage. “Who else could have wanted to hurt George Bush more than his rival, the former Vice-President al-Gur?”

The citizens of Cairo may be skilled at concocting diabolical scenarios, but they are not the only ones. Plenty of Africans from further south pooh-pooh the conventional view that the virus that causes AIDS originated with monkeys. It was cooked up in an American lab, of course, to kill black people.

Many Asians, including the prime minister of Malaysia, blame a clutch of Jewish financiers for causing their economies to crash in 1997. Some Jews, meanwhile, equate Amnesty International, which often criticises Israel, with the Nazi party. Credulous Indians see the hand of Pakistani intelligence behind everything from train crashes to cricket match fixing, and many Pakistanis return the compliment. Slobodan Milosevic, smug in court at The Hague, has testified that the 1995 massacre of 7,000 unarmed Muslims at Srebrenica was carried out not by Serb militiamen, but by French intelligence. Less whimsically, China's government launched its vicious campaign to crush Falun Gong in the belief that the movement, whose stated aims are to improve its devotees' spiritual and bodily health, is a dangerous cult bent on subverting the state.

Americans like a good plot too. The assassination of John F. Kennedy still generates a thriving industry, complete with a thicket of suggestive websites (see article), books, college courses, one big-budget movie and a whole vocabulary of arcana. (If you don't know what is pictured in frames 112 and 113 of the Zapruder film, or wonder what the Grassy Knoll is, better stay quiet on the subject.) A 1991 poll showed that, three decades after the president's murder, 73% of Americans still think he was a victim of conspiracy.

Such fables are nothing new. American pamphleteers in the 1790s warned of a plot by atheist, libertine Illuminati and Freemasons to concoct an abortion-inducing tea and “a method for filling a bedchamber with pestilential vapours”. The bestselling book of the 1830s was a racy confession by a repentant nun detailing a scheme by Catholics to undermine Protestant morals. At around the same time, Samuel Morse, better known as the inventor of Morse Code, exposed an Austrian plan to install a Hapsburg prince as emperor of the United States. In the 20th century, Americans feared reds more than royals; hence Joe McCarthy's witch-hunts, and the popularity of Father Charles Coughlin, who told radio audiences that “Masons and Marxists rule the world”.

In “Under Western Eyes”, Joseph Conrad wrote that “to us Europeans of the West, all ideas of political plots and conspiracies seem childish, crude inventions for the theatre or a novel.”

Some modern scholars go further, arguing that the conspiracist habit is a sort of disease or syndrome. The “paranoid thinker”, instructs material from a course at the University of Rhode Island, is “rigid, victimlike, cowardly”. This contrasts with the traits of the “rational thinker”, who is “open, flexible, empowered, strong”.

Daniel Pipes, the author of two books about conspiracy theorising, describes the classic grand theories—such as those about Masonic or Zionist or Papist plots for world domination—as:

a quite literal form of pornography (though political rather than sexual). The two genres became popular about the same time, in the 1740s. Both are backstairs literatures that often have to be semi-clandestinely distributed, then read with the shades drawn. Elders seek to protect youth from their depredations. Scholars studying them try to discuss them without propagating their contents: [with] asterisks and dashes in the first case and short extracts in the second. Recreational conspiracism titillates sophisticates much as does recreational sex.

Mr Pipes does good work in skewering anti-Jewish conspiracy theorists, but his recent founding of “Campus Watch”, a website devoted to “outing” pro-Arab academics, emits a whiff of burning books.

Belief in conspiracies is not necessarily foolish. Some are real. The Holocaust, for example, actually happened, though few believed it before the camps were liberated. Consider also the Bolshevik revolution of 1917: a small group of violent fanatics seized control of a large empire, as millions of their victims could testify, were they still alive. Businessfolk conspire, too. Adam Smith, a man to whom The Economist accords considerable respect, once wrote that: “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public.”

That some conspiracies are real, however, does not mean that they all are. As a tool for explaining how the world works, conspiracism has certain drawbacks. It inhibits trust: if everyone else is out to get you, better have nothing to do with them. It dampens optimism: if “they” are sure to frustrate your plans, why bother doing anything? And, of course, it leads to harmful errors, such as the belief, once popular among Africans, that condoms were yet another ploy to reduce their population.

The Evolution of Theories

So what is the attraction of conspiracism? For starters, as grand unifying theories of geopolitics go, it is simple to grasp. In ill-educated societies, that makes it appealing. It is also impossible to disprove, because any fact that does not fit the theory can be dismissed as a trick by the conspirators to throw ordinary folk off the scent.

In countries with opaque and authoritarian political systems, rumour is often the only alternative to official news sources. If the people in such countries remember falling victim to real conspiracies, they may be inclined to attribute fresh misfortunes to a similar cause.

|

Take more or less anywhere in the Middle East. The very borders of countries such as Jordan, Syria and Lebanon are a product of the 1916 Sykes-Picot accord, a secret agreement between Britain and France to divvy up the region between themselves, despite earlier British pledges of statehood to Arabs. In 1917, war-pressed Britain sought to curry favour with the growing Zionist movement by promising a “Jewish national home” in Palestine. The Palestinians, nine-tenths of the territory's population at the time, were not consulted. Thirty years later, when the UN voted to give Jews 53% of the land, the 13 “Eastern” countries that objected were overruled by 33 “Western” countries, which between them ruled over some 120 future members that surely would have voted otherwise had they been able to. Small wonder Palestinians see the world through a lens of victimhood. |

The Joy of Conspiracy overheard in a bar in Tel Aviv . . . Two Jews are sitting on a bench reading newspapers. One notices that the other's paper is a vile anti-Semitic rag. "Why read that trash?" he asks. "Well," says the second, "I used to read a paper like yours. But it was too depressing: all that news about suicide bombs and Ariel Sharon. My newspaper, on the other hand, is full of good news: apparently we control all of Hollywood, own all the banks, dominate American politics . . ."

|

In the West, conspiracies have, for some reason, tended to fail, and so fade from the popular imagination. Who now frets about the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, when a gang of Catholics failed to blow up Britain's Parliament? Or the doomed Carlist uprisings in 19th-century Spain? Or the European anarchists who assassinated seven heads of state in the 1890s, to no avail? Or the Watergate scandal?

In Iran, by contrast, people still seethe over the CIA-backed coup of 1953 that toppled Muhammad Mossadegh, a man much loved for having dared to nationalise British oil interests. Syria and Iraq have suffered a dizzy sequence of successful plots and counter-conspiracies, ending with the pair of Baathist coups in the late 1960s that installed their current ruling cliques.

Half the governments of the Middle East trace their origins to coups. In a sense, conspiracy is the region's only real form of politics, which can make it hard for Middle Easterners to understand the dynamics of open, democratic societies. Hence, for example, the Arab tendency, as the French say, to “occult” America's generous backing for Israel. Aiding the Jewish state infuriates hundreds of millions of oil-supplying, American-product-consuming Arabs and Muslims. So why does America do it? It must be a conspiracy by the Zionist lobby, or perhaps a plot to divide and rule Arabs to control their oil, or part of a Christian crusade against Islam.

Blaming others for one's troubles may be emotionally satisfying, but it is a counsel of despair. Stella Orakwue, a journalist, writes in the New African that: “Today, [Africa] has to remain in deficit so Europe and America can maintain their obscene wealth.” Given that Africa accounts for less than 2% of global trade, this is hardly an adequate explanation of why the West is rich and Africa is poor. And without understanding why their continent is poor, Africans will find it harder to grow rich.

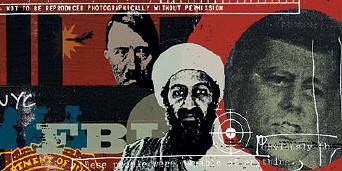

In extreme cases, conspiracy theories can cost lives. Osama bin Laden genuinely seems to think he is fighting a Zionist-Christian-materialist assault on Islam. Adolf Hitler sincerely believed he was ridding the world of a Jewish menace. Many Serbs were convinced that the Muslims of ex-Yugoslavia were out to annihilate them. And many Rwandan Hutus, informed by their leaders that the Tutsis were planning to kill them, were happy to follow orders to pre-empt this threat.