It Isn't Easy Being “Green”

William S. Abruzzi

(2009)

I recently distributed a survey in my First Year Seminar and received the following results:

The average number of cars per household in the class is 2.7 (3.4 if I included only those whose family had cars), ranging from 0 to 5.

The average number of TVs is 3.9 (ranging from 2 to 7).

The average number of computers is 2.7 (ranging from 2 to 6).

The average number of stereos, Walkman, etc. is 7.5 (ranging from 4 to 18).

The average amount of money estimated to have been spent on Christmas and/or Hanukah was about $1,800 (ranging from $300 to $3,000).

Only 3 people in the class indicated that they had bought used clothing in the past 6 months, compared to 8 who had purchased new clothes at retail stores, with 6 individuals having made multiple visits to those stores.

Half the students (5) indicated that they had taken at least 1 airplane trip this past year, and 2 had taken at least 1 overseas flight.

While far from being a "scientific" survey, the above results are probably representative of Muhlenberg students as a whole. Due to the expense of attending a small private liberal arts college (SPLAC), students at Muhlenberg and other SPLACs are disproportionately drawn from the upper middle class, whose per capita income and resource consumption exceeds that of the general population. As a result, SPLAC students and their families contribute disproportionately to environmental degradation and other environmental problems, as is illustrated below.

Air Travel and the Environment:

According to The Guardian (Feb. 22, 2006), a British newspaper,

“Aviation emissions (in Great Britain) rose by 12% last year and now account for about 11% of Britain's total greenhouse gas emissions - the fastest growing sector. The government's chief scientific adviser, Sir David King, has described global warming as a bigger threat to the world than global terrorism.

According to British Airways,

“The most authoritative report on the impact of aviation on climate change is the study by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) "Aviation and the global atmosphere", published in 1999. This showed that aviation was responsible for 2% of CO2 emissions - the most important greenhouse gas - and around 3.5% of man-made global warming in total.”

According to Beatrice Schell, a spokeswoman for the European Federation for Transport and Environment,

"One person flying in an airplane for one hour is responsible for the same greenhouse gas emissions as a typical Bangladeshi in a whole year." And every year jet aircraft generate almost as much carbon dioxide as the entire African continent produces.”

Given that it takes about 6 hours to fly to Europe, an American flying to Paris produces as much greenhouse gas emissions during that one round-trip flight as a typical individual living in a developing country generates in 12 years. Travel to Europe is more common among middle and upper-middle income Americans than among the poor or working class.

Professionals who fly frequently (either for business or pleasure), including college professors and environmentalists who fly across the country and around the globe to attend multiple conferences each year, are among the world's highest producers of aircraft-borne greenhouse gases.

Housing and the Environment:

A commercial-grade timber tree can range from 9" to well over 20" in diameter. A 9" Ponderosa pine yields about 17 board feet* of lumber, while a 17" Ponderosa pine yields about 135 bf.

*Board Foot (bf) -- a unit of measure one foot long, one foot wide, and one inch thick or its equivalent

It, therefore, takes anywhere from 100 to 700 trees to build the average-sized American house.

It takes even more trees to build bigger suburban houses, especially the modern “Starter Castles” or “McMansions”, as the progressively larger houses being built today are referred to by environmentalists.

The middle and upper-middle class, who are the ones purchasing these larger homes, are thus responsible for far more resource consumption and “environmental degradation” than the lower and lower-middle classes who disproportionately occupy the smaller townhouses being built.

Those who purchase existing homes (which generally cost much less per square foot) cause little or no “environmental damage”, except for what materials they might purchase to improve or remodel those homes.

The bigger the house, the greater is the energy required and the pollution generated to heat, air condition and illuminate it. Thus, older row houses of the type seen in most urban neighborhoods (most notably in poorer neighborhoods) are much more “environmentally friendly” than the substantially larger single-family homes which characterize the expansive suburban neighborhoods surrounding most cities.

Cars and the Environment:

The average automobile weighs around 4,000 lbs., while the average SUV weighs closer to 6,000 lbs. or more. The manufacture of automobiles requires several environmentally expensive processes, including: (1) mining for iron and the other ores that go into making steel; (2) the extensive consumption and pollution of water required to separate iron ore from the surrounding sediment, to smelt steel, and to assemble the finished automobile; (3) the air pollution created by both mining and manufacturing processes; (4) the energy (oil, coal, etc.) consumed to power mines, steel mills and automobile assembly plants; (5) the environmental cost created by shipping raw materials, manufactured parts and the finished automobiles; plus (6) the environmental costs involved in manufacturing and shipping the various non-metal materials used to produce an automobile (e.g., windows, seats, carpets, dashboards, tires, etc.).

An aluminum can weighs ½ ounce, which means that it takes 32 cans to equal 1 pound.

It would, therefore, require recycling approximately 128,000 aluminum cans to recycle the amount of metal needed to offset the environmental cost of producing one car (recognizing that cars are made of steel not aluminum). This does not, however, offset the other materials that go into the production of a car, such as fabric for seats and upholstery, glass for windows, plastic for dashboard and other items, including the nylon or rayon used to make tires.

If the average person recycles 3 aluminum cans per day, it would take 42,666 days (over 116 years) to recycle the amount of metal consumed by the purchase of one new 4,000 lb. automobile. It would, thus, require 350 years to recycle the metal equivalent of 3 cars purchased over a 10-year period. The total amount of cans that would have to be recycled would clearly be higher for SUVs, minivans and luxury sedans than it would be for smaller compact cars. In addition, larger vehicles are less fuel efficient, making their overall environmental cost even higher. Larger vehicles are more commonly purchased by members of the middle and upper-middle income classes than by the poor and those in the lower-middle classes.

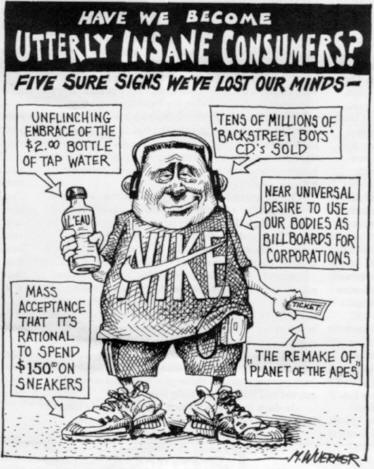

Consumerism and the Environment:

In general, due to the higher standard of living and levels of consumption that exist in the U.S., some environmentalist have estimated that it takes as much energy and resources to raise one child in the U.S. as it does to raise 100-200 children in Africa. Clearly even more energy and resources is consumed to raise a child in an upper-middle income American family.

William Rathje (RUBBISH! The Archaeology of Garbage) calls Christmas as “a solid-waste tsunami”.

According to Unity Marketing's survey of over 600 consumers conducted in early January 2006, the average amount spent per person buying Christmas gifts in 2005 was $793 .

Comparison of Various Holiday Expenditures in the U.S. (total and per capita)

Christmas (Hanukkah and Kwanzaa) $220 Billion / $700 per person

Valentine's Day $13 Billion / $110 per person

Mother's Day $11.5 Billion / $105 per person Easter $9.5 Billion / $100 per person

Father's Day $8 Billion / $80 per person

Halloween $3 billion / $30 per person

Consumption is directly related to income; on average, those who earn more spend more on consumer items. Since there is a direct relation between the dollar amount spent and the environmental cost incurred, those who earn more generate a greater proportion of direct and indirect environmental degradation in the form of mining, air and water pollution and the other byproducts of producing consumer goods. Thus, individuals in the middle and upper income segments of the population are disproportionately responsible for a greater share of the environmental costs of consumer spending than are the poor and those in lower socioeconomic classes.

Colleges and the Environment

About 3% of the college students in the U.S. attend small private liberal arts colleges (SPLACs).

These institutions cost between $30,000 and $40,000 per year for tuition, compared to about $10,000 per year for a state college in the Eastern U.S. and $3,000 per year for a state institution in the Western U.S.

Students at private colleges in the U.S. are, thus, more likely to be from the upper and upper-middle income families than are those students who attend state and community colleges.

It is reasonable to conclude, therefore, that in housing, automobile consumption, travel and general consumer behavior students (and faculty) at private colleges are disproportionately responsible for more resource consumption and environmental degradation than members of the general population.

|

|

|

|

|

|

↑

Which of the social classes represented by these residences likely consumes more of the earth’s resources?

↓

|

|

|

|

|

|

* * * * *

Which of the above social classes is most represented at the Muhlenberg?

Conclusion

While recognizing that those individuals who are involved in environmental activities on campus are genuinely committed to what they are doing and sincerely believe that their activities make a difference in “protecting the environment”, it is rather ironic (to say the least!) to see active environmental organizations and environmental study programs at private institutions. It is precisely at these institutions that the per capita consumption level and the relative environmental cost of maintaining the individuals in their populations are among the highest in the world. It, therefore, seems rather incongruous to have members of the environmentally expensive upper-middle class organizing recycling programs and other “green” activities, which have at best a trivial impact on reducing resource consumption and environmental degradation --especially when the impact of these activities is compared to the environmental cost of the high level of resource consumption maintained by the very same people in their normal daily lives. It seems somewhat comparable to having drug dealers and Mafia members participating in local community crime-reduction programs. Those who see an environmental "crisis" looming in the horizon might reasonably compare such activities to treating cancer with a Band-Aid, or to rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Pharisaic Environmentalism

Middle and upper-middle class environmentalism may also be compared to Jesus’ parable of the Pharisee and the Publican, as told in the Gospel of Luke. In the parable, the Pharisee boasts proudly of how devotedly he follows God’s law. According to Luke,

Two men went up to the temple to pray, one a Pharisee and the other a tax collector [Publican]. The Pharisee stood up and prayed about himself: “God, I thank you that I am not like other men—robbers, evildoers, adulterers—or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week and give a tenth of all I get.” But the tax collector stood at a distance. He would not even look up to heaven, but beat his breast and said, “God, have mercy on me, a sinner.” I tell you that this man, rather than the other, went home justified before God. For everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, and he who humbles himself will be exalted. (Luke 18:10-14).

In other words, while the Pharisee publicly praised himself for the superiority and righteousness of his behavior, the Publican humbly accepted that he sinned and just did the best he could. According to William Rathje, It is the poor and the working classes who do the "real recycling" --in contrast to the mere “sorting and collecting” that results from recycling programs. It is the poor and members of the lower socioeconomic classes that actually purchase used clothing, automobiles and other consumer goods discarded by those in the middle and upper-middle classes. The poor and working classes are also much less likely to take expensive long-distance vacations. They do this not because they have any greater ideological commitment to the environment than those in the middle and upper-middle class, but because they cannot afford to spend as much money. Yet, it is disproportionately members of the middle and upper-middle income groups who (like the Pharisee) express the greatest commitment to the environment, who promote environmental programs and who disproportionately belong to such environmental organizations as the Sierra Club and The Nature Conservancy, --while at the same time purchasing more consumer products than the average individual, driving new and bigger cars (even buying wilderness license plates for their SUVs), living in larger homes and traveling on environmentally expensive long-distance vacations, including environmentally expensive “ecotours”.

It isn’t easy being green . . .

Yuppie Environmentalism:

Use an "environmentally responsible" credit card to ease your conscience while you buy the TV's, VCRs, designer clothes made in Asian sweatshops and the gas to feed your Sports Utility Vehicle.

* * * * *