The

Jesus

Movement

|

The following information is presented which suggests that Jesus may not

have been a "Prince of Peace" bringing a message of universal love to all

mankind, but rather may have been more militant and more specifically Jewish

in his orientation than is generally recognized. He may even

have posed a potential political threat to the Roman colonial administration

in Judea and to the local Jewish leadership (the Sadducees), both of whom

had a vested interest in maintaining the peace

and eliminating those who they believed encouraged political

unrest.

|

|

|

|

1.

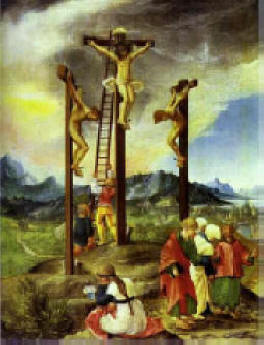

Jesus was tried and executed by a Roman official (Pontius Pilate) for

treason against the state of Rome. This was a political crime, not a

religious one, and Jesus received the punishment specifically reserved for

treason under Roman law --crucifixion.

Given that Rome punished traitors with crucifixion, Jesus' statement (as

quoted in Mark vii:34) that "if any man would come after me, let him deny

himself, and take up his cross and follow me" had real meaning to his

Jewish compatriots bristling under the onus of Roman rule. As

Brandon (1967:145) notes, "The cross was the symbol of Zealot

sacrifice before it was transformed into the sign of Christian Salvation."

(The

Zealots

were a radical political faction among the Jews that undertook

insurrection against Roman occupation of Palestine during the first

century CE.) The account of Jesus' trial which presents Pilate as

believing in Jesus' innocence, but forced into pronouncing him guilty by

the Jewish leadership (Mark xvi; Luke xxiii; Matthew xxvii; John xix), is

both illogical and without factual basis. (The Gospel of Mark is the

earliest gospel. Its version of the trial and crucifixion is the original

version upon which the other three gospels increasingly elaborated.)

a.

We have considerable information about Pilate from several

non-Biblical sources. These sources consistently describe Pilate as a

stern government official who frequently demonstrated his toughness in

dealing with the Jews. On several occasions,

he instituted actions designed to intimidate both the Jewish population

and its leadership in order to illustrate his power and assert his

authority. It is highly unlikely that

Pilate would have been pressured by the Jewish authorities into convicting Jesus of sedition if he did not

believe that Jesus was guilty.

b.

The story of Pilate releasing Barabbas instead of Jesus is

also unrealistic. No evidence exists of a custom of releasing one Jewish

prisoner during the Passover, other than its

mention in the New Testament. Not even

Josephus, the principal Jewish

historian of the day, mentions it. Indeed, it is highly unlikely that

Rome would have followed such a practice in the most rebellious province

in its empire (or in any other province, for that matter). The Roman

government releasing a Jewish prisoner who had murdered Roman soldiers

during an insurrection as a Passover gesture would be comparable to the

Israeli government releasing a Hamas or Abu Nidal terrorists during

Ramadan, or to the British government releasing an IRA terrorist on St.

Patrick's Day.

c.

Furthermore, as Brandon (1967:4) points out, "Mark

presents Pilate, a Roman governor, not only as criminally weak in his

failure to do justice, but as a fool beyond belief. . . . To have offered

the people such a choice . . . (Jesus or Barabbas) . . . with the intention of

saving Jesus, was the act of an idiot." Given the political climate at

the time, the Jews would clearly have preferred to free a Jewish

nationalist, such as Barabbas, rather than a man who the gospels claim

said "Love the Romans" and "Render unto Caesar the things that are

Caesar's."

d.

Finally, if Pilate undertook such an action

independently, he would have had to answer to his superiors. If Jesus

was, in fact, preaching a philosophy of peace towards the Romans while Barabbas was killing Roman soldiers, Pilate would have put himself in

grave jeopardy by releasing Barabbas and executing Jesus. He would likely

have found himself convicted of treason and crucified.

2.

Jesus was crucified between two "thieves". The Latin term used to refer

to these "thieves" was

lestai.

This was the term the Romans used to refer to the

Zealots.

It more correctly means "brigands" or "terrorists" rather than thieves.

In the Gospel of John (xviii: 40), Barabbas is said to be a

lestai.

Barabbas was arrested for attacking the Roman garrison in Judea. This

attack appears to have occurred simultaneous with Jesus' attack on the

Temple. Some Biblical scholars believe that Jesus and Barabbas may have

been working together. Significantly, the name Barabbas is a corruption

through translation of the Hebrew term

bar abba which means "son of the

father". In the Gospel of Matthew (xxvii:16), Barabbas is referred to as

Jesus Barabbas, which translates to mean Jesus son of the father, the

equivalent of "Jesus, Jr." in English. One implication of Matthew's use

of the name Jesus Barabbas is the possibility that Barabbas may have been

Jesus' son. However, Jesus is the Greek translation of the Hebrew

name, Joshua, which was a common Jewish name that would have been given to

many men besides Jesus of Nazareth.

3.

At least one of Jesus' apostles was a Zealot. Luke

(vi:15) indicates that the apostle Simon was a Zealot (see also Acts

i:13). Some Biblical scholars think that Judas Iscariot may also have

been associated with the Zealots. Another radical group, known as the

Sicari,

existed at the same time as the Zealots. It is unclear whether the Sicari

were an elite group within the Zealots or a separate group pursuing the

same political goal

(see

Horsley 1979;

Hoenig 1970;

Smith 1971). The name Sicari means "dagger men." It was derived

from the word

sica, the Latin term for a small dagger. The members of

this group were called Sicari by the Romans because they used small

daggers to assassinate prominent Jewish leaders who they believed had

betrayed the Jewish people in order to maintain their positions of

prominence in the local community The name

Sicari derives

from the Latin,

sicarius,

which is remarkably close to Iscariot (simply invert the first two letters

of the word sicarius and replace the Latin ending [us] with the Greek

ending [ot] and you have Iscariot.) John (xiii:2) states that Judas

Iscariot was Simon the Zealot's son. If this is true, then Judas, like

his father Simon, may also have been a Zealot.

Significantly, in one exchange Judas criticizes Jesus for wasting money

anointing himself with oil when the money in question could have been

given to the poor (see John xii:5). This would have been precisely the

kind of issue that would have concerned a Zealot fighting for the

interests of the poor. Interestingly, Jesus' response to Judas' criticism

was a rather cavalier one, showing little regard for the welfare of the

poor: "You always have the poor with you, but you do not always have me."

(John xii:7). (Jesus' reply to Judas sounds remarkably similar in tone to

Marie Antoinette's infamous response to the poor of France who complained

that they could not afford bread: "Let them eat cake.") Judas' betrayal

of Jesus was more likely for socio-political reasons than for a mere 30

pieces of silver. Indeed, Matthew is the only evangelist to mention a

specific price of 30 pieces of silver. He simply borrowed the amount from

a quote in Zechariah (xi:12) in order to link Jesus with Old Testament

prophecy, which Matthew

--and only Matthew-- does

repeatedly! In fact, the gospel attributed to Matthew contains 19

Old Testament parallels

and 11

"fulfillment citations", none of which are

contained in any of the other gospels.

|

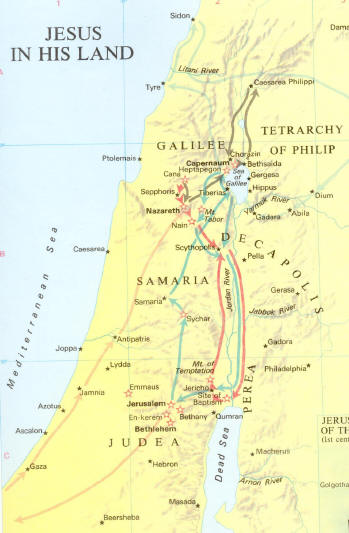

4.

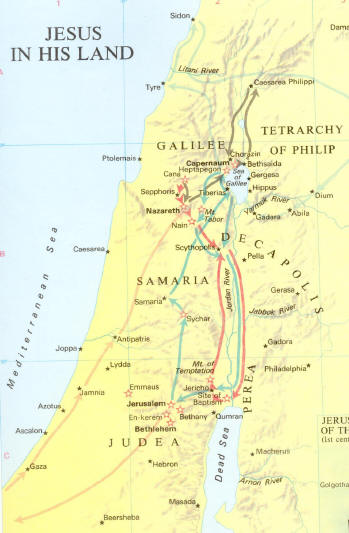

Jesus came from

Galilee

and was in many ways a typical Galilean prophet, at least as he is

portrayed in Mark and Matthew. Exorcisms and healings of the sick

were a standard part of the repertoire of other Galilean prophets as well (see Vermez

1973). Galileans were considered by Judeans to be largely ignorant

of the fine points of Jewish Law, in part because they

retained their provincial identity and resisted the political, economic

and cultural dominance of Judea. Many of Jesus' disagreements with

the Pharisees (who were very concerned with upholding the Law) were

typical of Galilean laxity toward the Law, which was viewed by many

Galileans as a vehicle of Judean dominance over Galilee. For

this reason, the general Judean attitude towards Galilean prophets was a

condescending one, not unlike the attitude that many mainstream Christians

today have towards fundamentalist preachers in Appalachia and the rural

South.

|

|

|

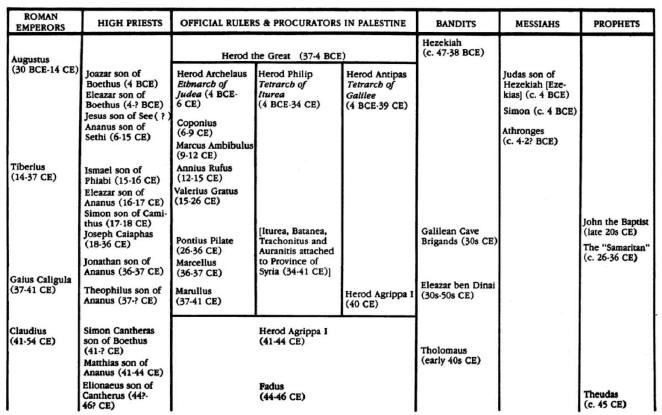

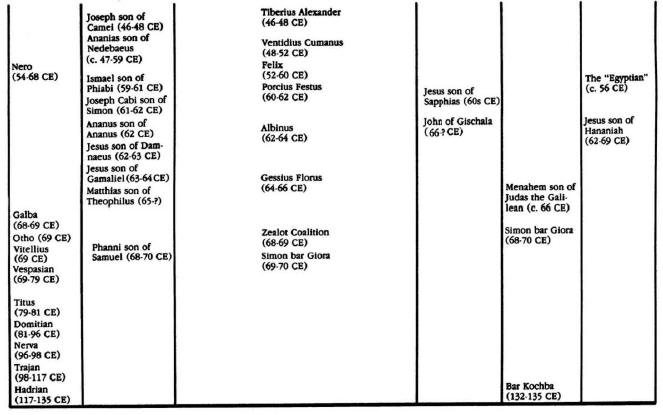

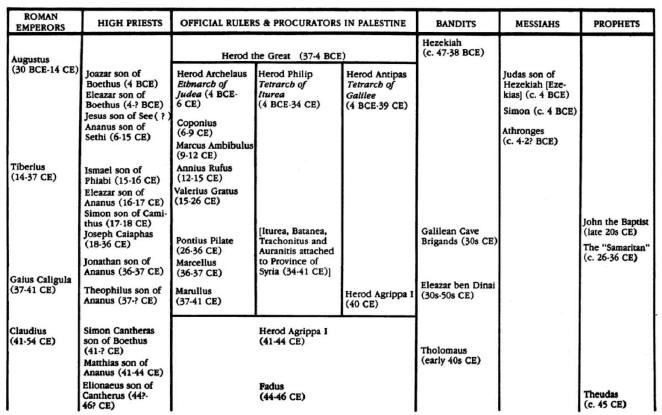

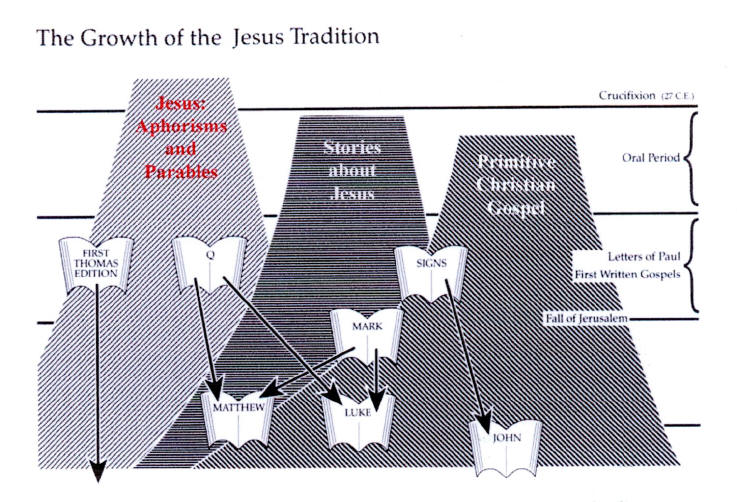

Horseley and Hanson

(1985) list at least 5 major bandit gangs, 6 messianic claimants and 5

self-proclaimed prophets (not including Jesus) that roamed the

Palestinian countryside during the first century

CE (see chart below).

Roman occupation of Palestine imposed an economic hardship on indigenous

peasant communities, and

Galileans played a prominent role in the militaristic-messianic

revolt against Roman rule that persisted throughout the the latter half

of the first century BCE and the first and early second centuries

CE. While serving his father, Herod executed a Galilean insurgent named Ezekias, who had a large following. Some

forty years later, upon Herod's own death, Ezekias' son Judas led a

revolt against Roman rule which resulted in his crucifixion and that of

2000 other rebels. In 6 CE, another Judas of Galilee, founded the

Zealots

(also called the

Fourth Philosophy

to distinguish it from the teachings of the Sadducees, Pharisees and

Essenes) and led a revolt against the imposition of direct Roman rule.

This revolt was sparked by the Roman census of Judea conducted that

year. This census, which is mentioned in Luke (ii:1), was

undertaken, as most censuses are, for the purpose of collecting taxes

(see Abruzzi, When Was Jesus Born?).

The exact fate of Judas and his followers is not known. However, Acts

(v:36-37), states that, like Theudas before him,

Judas "also perished, and all who followed him were scattered." The

mantle of Judas' leadership passed to his two sons, who were

subsequently crucified in 46-48 CE. Judas' third son, Menahem,

initially led the revolt against Rome in 66 CE. Finally, Eleazar, the

leader of the rebels at Masada (all of whom died in 73 CE) was also a

Galilean and a descendent of Judas. So strong was the tradition of

revolt in Galilee, that the terms Galilean and Zealot were frequently

used synonymously by the Romans. Roman occupation (like most

colonial situations)

spawned numerous prophets, most notably Theudas, "The Egyptian" and John the

Baptist. The message that these prophets taught was very similar

to that attributed to Jesus: the imminent end of the world and God's

impending judgment of humankind.

Jesus, thus, lived

during a period of heightened messianic fervor and of intense political activity against Rome.

He also lived in the

very province that served as a center of revolt. Jesus, therefore, grew up

in a land in which men like Judas of Galilee and his brothers were

considered martyrs and messengers of God, much as the Maccabees had been

viewed before them (and in much the same way that the leaders of Hamas

and Hezbollah are viewed by many Palestinians today). As a young

boy, Jesus could not have escaped being influenced by the events and the

intense feelings of the people around him. Furthermore, if he were

successful at attracting a large following in such a highly charged

political context, it would be highly unlikely that this following would

have been based on a message of love for the Romans and kindness towards

one's enemies. More likely, Jesus' popularity would have been

based on the compatibility of his mission with the tradition of a

militant Messiah represented by such popular Jewish leaders as Judas of

Galilee, Judas Maccabee, King David and Bar Kochva.

If

we look at the men Jesus chose as apostles, all of whom were Galileans

(There were no Judean apostles and, certainly, no Gentiles),

we see at least five who displayed a propensity towards violence. As

already indicated, Simon was a Zealot and Judas was likely a Sicari

and/or a Zealot. Another Simon was nicknamed Peter (meaning Rock, or

possibly the equivalent of "Rocky") and used a sword to cut off a

soldier's ear in the Garden of Gethsemane (Mark xiv:47; John xviii:10).

And both James and John, the sons of Zebedee, were also known as the

Sons of Thunder

(Mark iii:17) because of

their violent tempers. Indeed, at one point they wanted to destroy a Samaritan

village because its residents refused to allow Jesus to enter their

village (Luke

ix:54).

Bandits, Prophets, Messiahs

and Other Political Players

at the Time of Jesus

|

|

SOURCE: Horsley and Hanson (1985)

|

|

5.

The version of Jesus that has come down through the

centuries derives primarily from Paul (who was not an apostle and who, in

fact, never met Jesus),

and from the four canonical gospels, which:

(1) were written primarily

for

Gentile audiences, and

(2)

were written between 40 (Mark) and 70 or more

(John) years after Jesus had died. Thus, none of the New Testament

sources can be considered

"eyewitness"

accounts. Applying standard techniques used in the study of oral

literature, Funk, Hoover and the 76 Biblical scholars that constituted the

Jesus Seminar

(1996) concluded that only about 20% of the sayings of Jesus in the gospels

can be confidently attributed to him. (Significantly, not a single quote in

the entire Gospel of John was considered authentic by these scholars. The

gospel that was considered the most authentic was the

Gospel of Thomas, one of 16

Gnostic Gospels,

all of which were

rejected by the early Church as heretical and excluded from

the Christian Bible.) Because all four canonical gospels were

written several decades after Jesus had died, they were completely removed

from the political conditions in Palestine at the time Jesus lived. They

were also written by individuals who did not live in Palestine.

Also, given the

embarrassing fact that

Jesus was crucified by a Roman governor (and the fact that crucifixion was

largely reserved for the lowliest criminals (see Samuelsson 2011), the gospels were increasingly

concerned with separating Jesus from the political context of Roman

Palestine. The gospels are, therefore, completely silent regarding the

political events contemporary with the life of Jesus, political events that

convulsed the very land in which Jesus lived and preached. As Marvin Harris

(1974:161) notes,

From the gospels alone, you would never know that Jesus spent most of his life

in the central theater of one of history's fiercest guerrilla uprisings. You

could never guess that in 68 AD. ...(CE)... the Jews went on to stage a

full-scale revolution that required the attention of six Roman legions . . .

(about 36,000 soldiers) . . . under the command of two future Roman

emperors before it was brought under control.

6.

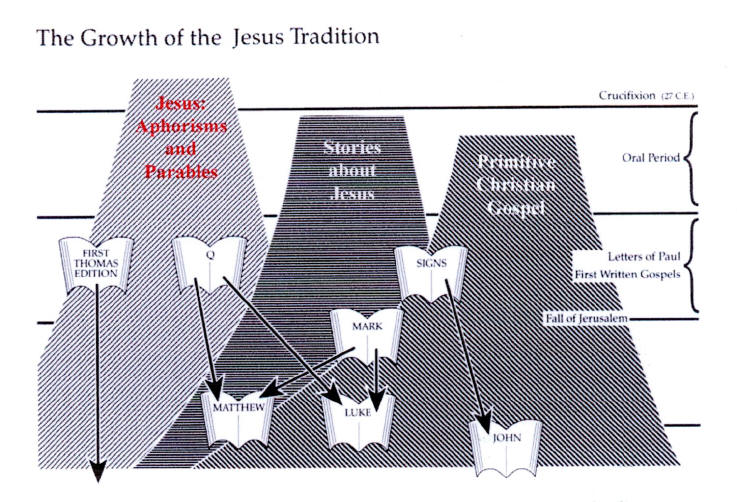

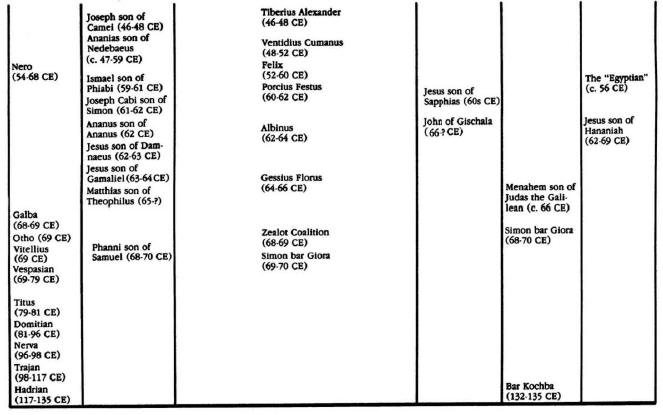

Furthermore, the Gospels themselves evolved through time.

Mark's gospel (70-75) is universally considered the first gospel by biblical scholars,

followed by Matthew (80-85), Luke (80-90) and John (90-100). In

addition, the four canonical gospels cannot be considered independent of one

another. About 80% of the verses in Mark are reproduced in Matthew, and

about 65% are reproduced in Luke, in largely the same order as they appear in

Mark. Consequently, the fact that a particular story exists in more than

one gospel does not necessarily increase that story's validity, since the

later gospel writer quite likely borrowed the story from the earlier gospel

(see Abruzzi,

The Birth

of Jesus).

Moreover, in addition to Mark, there are other

earlier sayings gospels that scholars believe existed and contributed to the

various gospels. One proposed source called

"Q" is believed to

be the origin of certain similarities between Mathew and Luke, while a

radically different earlier source, referred to as

"Signs", is thought

to have influenced John (see chart below).

| |

SOURCE: Funk, Hoover, et.al. (1993).

|

|

Mark's gospel begins with Jesus' baptism by John the Baptist. There is no

birth story in Mark, no visitation by Magi or by shepherds, no Christmas star,

no virgin birth, no "Slaughter of the Innocents" by Herod, and no census

forcing Joseph and Mary to go to Bethlehem. Each one of these stories is

presented in either Matthew or Luke. However, none of the same stories is contained in both gospels.

In fact, Matthew's and Luke's versions of the birth story contradict each

other in practically every detail (see Abruzzi,

When Was Jesus Born?). Indeed, the two gospels tend to agree with one another primarily where they

closely follow Mark's earlier account, because they likely borrowed those

stories directly from Mark's gospel. They tend to flatly contradict one

another where they contain material that was not previously borrowed from

Mark. Matthew and Luke completely contradict one another regarding events

surrounding the birth of Jesus, because none of this material is included in

Mark. They even contradict one another regarding the very year Jesus was

born. Matthew claims that Jesus was born during the rule of Herod the

Great. We know from Roman records that Herod died in 4 BCE. Luke, on the

other hand, claims that Jesus was born during the Roman census of Judea. That

census occurred in 6CE, ten years after Herod's death. It is unlikely

that either Matthew or Luke presents the correct date of Jesus' birth.

Furthermore, whereas Luke states that Jesus and his family came to Bethlehem

for the census and returned to Nazareth immediately afterwards, Bethlehem was

where Joseph and Mary lived in Matthew. Moreover, Matthew has Jesus and

his family flee to Egypt until the death of Herod before settling in Nazareth,

because they could not return to Bethlehem. Each author chose their respective settings for Jesus' birth in order to

create a dramatic context within which to place his birth in order to enhance

their story. For Matthew, Jesus' escape from

Herod's "Slaughter of the Innocents" was a replay of Moses' escape from the

Pharaoh's killing of the first born in Exodus (1:16-22) and the

Israelites escape from Yahweh's genocidal slaughter of Egyptian children (see

Exodus 11 & 12) in the

Hebrew Bible (the Christian's Old Testament). Luke, on the

other hand, was not as tenaciously concerned with linking Jesus to Old Testament

prophecy, as

was Matthew, but showed more interest in placing Jesus' birth in the context of the Gentile Roman world

in which he existed. So, he placed Jesus' birth at the time of the Roman

census of Judea.

Similarly, the picture of Jesus evolves through the four gospels. Jesus is portrayed

in Mark and Matthew as a prophet primarily to the Jews, while he is presented

as a prophet to Jew and Gentile alike in Luke, and as the savior of all

mankind in John. Jesus preaches only among Jews in Mark and

Matthew. It is also in the first two gospels that Jesus refuses to

cure a

Syrophoenician woman's daughter

because the woman is a Gentile (Mark

vii:24-30; Matthew xv:21-28), and it is in Matthew (x:5-6) that he explicitly

instructs his apostles not to preach among the Samaritans but to preach only

among the Jews. In contrast, it is in Luke (ix:55) that Jesus restrains

James and John, "The Sons of Thunder", from destroying a Samaritan village

because its residents refuse to let Jesus preach there. We also see the

parable of the

"Good Samaritan"

only in Luke (x:30), as well as the story of Jesus curing 10 people in which

only the

Samaritan

returns to thank him (Luke xvii:16-17). And, finally, in John (iv:9-10,

22-23), Jesus shares a cup of water with a Samaritan woman and tells her that

she will be with him in heaven. Later, when the woman tells other

Samaritans about Jesus, they invite Jesus to stay in their village, which (in

direct contradiction to Mark and Matthew) he does for two days. They also immediately believe in Jesus as the messiah,

so charismatic is his presence (iv:39-40), again in direct contrast to Mark and Matthew where Jesus'

message is rejected by his contemporaries, Jew and Samaritan alike. The

Samaritans were the descendents of the former

Northern Kingdom

(see

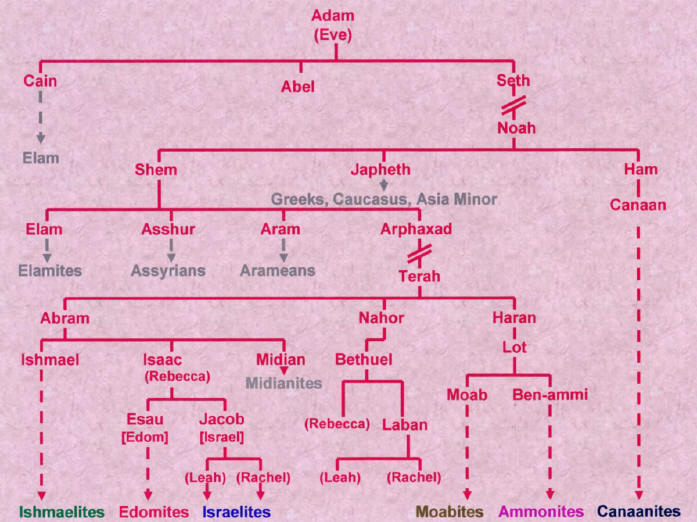

Genealogy, Politics and History in the Book of Genesis) that

split from the Kingdom of David and Solomon upon Solomon's death. There

had always been animosity between the Judeans and Samaritans, and Luke (a

Gentile) was

playing upon that animosity in portraying the Samaritans in a good light.

The

same evolution of Jesus from local Jewish prophet to universal messiah can be

seen in his relation to the two "thieves" (lestai) next to

him on the cross. Whereas in Mark (xv:27) neither thief says anything to

Jesus, in Matthew ( xxvii:44) both thieves revile Jesus along with the rest of

the crowd gathered at the crucifixion. In Luke (xxiii:39-43), on the

other hand, one of the thieves (the

"Good Thief") acknowledges Jesus as the

messiah and is told by Jesus that "today you

will be with me in Paradise." No

thief is mentioned in John.

7.

The parochialism and possible insignificance of Jesus and his mission in

Palestine is strongly suggested by the fact that

no first-century sources outside the New Testament

clearly mentions him. No Roman records have survived that contain details

about Jesus or any of his contemporaries in Palestine. The earliest Roman source

that exists is a second-century reference to Jesus by the Roman Senator and historian,

Publius Cornelius

Tacitus. Tacitus (116-117 CE) refers to Jesus in his

Annals

(15: 44) in conjunction with his description of Nero's burning of Rome in 64

CE. According to Tacitus, in order to counteract accusations

that he himself had initiated the fire, Nero blamed the conflagration on

Christians. While

Tacitus' reference to Jesus corroborates elements of Christian belief, it

is not clear where Tacitus obtained his information. It could quite easily

have come from Christians themselves.

Hence to

suppress the rumor, he falsely charged with the guilt, and punished

Christians, who were hated for their enormities. Christus, the founder of the

name, was put to death by Pontius Pilate, procurator of Judea in the reign of

Tiberius: but the pernicious superstition, repressed for a time broke out

again, not only through Judea, where the mischief originated, but through the

city of Rome also, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of

the world find their center and become popular.

Josephus,

the principal Jewish historian of

the first century CE, appears to have mentioned Jesus twice in his

Antiquities

of the Jews

(18.3.3 and 20.9.1), first in a general description of Jesus, and second in

relation to the execution of Jesus' brother James. The first reference

constitutes a one-paragraph description of Jesus (18.3.3) that is included in

Josephus' discussion of the various Jewish

"prophets" and messianic claimants that appeared in Palestine during

the reign of Pontius Pilate. The authenticity of

this paragraph, however, is highly suspect. It is generally considered by biblical

scholars to have been inserted later by a Christian scribe. The

paragraph states:

At this time

there appeared Jesus, a wise man, if

indeed one should call him a man. For he was a doer of startling deeds, a

teacher of people who receive truth with pleasure.

And he gained a following both among

many Jews and among many of Greek origin.

He was the Messiah.

And when Pilate,

because of an accusation made by the

leading men among us, condemned him

to the cross, those who had loved him previously did not cease to do so. For he appeared to them on

the third day, living again, just as the divine prophets had spoken of these

and countless other wondrous things about him.

And up until this very day the tribe of

Christians, named after him, has not died out.

This paragraph is considered inauthentic (either wholly or in part) for several reasons. First of all,

it differs sharply both in its writing style and vocabulary, as well as in the tone of its commentary,

from the surrounding narrative. While Josephus depicts

most of the

other bandits, prophets, terrorists, and messianic pretenders that arose

during Pilate's administration in largely negative terms, the paragraph in

question provides an

uncharacteristically glowing portrait of Jesus. Josephus was an upper class

Pharisee, who had little respect for those who claimed to be

either prophets or messiahs --of which there were many during the first

century CE (see Horsley and Hanson 1985). He, in fact, blamed them and their

actions for the eventual destruction of Jerusalem by Rome in 70 CE. It is,

therefore, highly unlikely that Josephus would have provided a glowing description of

Jesus had he, indeed, claimed to be either a prophet or the messiah.

Furthermore, Josephus' description of Jesus does not appear until

the fourth century. No church leaders prior to this time mention

Josephus' statement, even though the existence of such a declaration would clearly have

served their purposes. For example, while Origen (c. 185-254 CE) quotes the

paragraph mentioning Jesus in relation to the execution of James on three

separate occasions, he never once mentions the description of Jesus presented

in the above paragraph, suggesting that the paragraph did not appear until

after Origen's death.

Now Origen not only does not

quote the Christian passage, but he uses such language as to make it

impossible to maintain that the words "he was the Christ" appeared in the

text, for he says: Though he (Josephus) did not believe in Jesus as the

Christ, he none the less asseverates that the calamity of the destruction of

the Temple came upon the Jews for putting to death James, who was most

distinguished for his justice. If the Christ passage really appeared in

Josephus, it would be hard to believe that Origen, who

quotes the

James passage, should not know the other passage, which is recorded in the

same chapter. (Zeitlin 1928: 233-234)

Most Importantly, those portions of Josephus' quote

highlighted in

lavender indicate that the description of

Jesus contained in the above paragraph and attributed to Josephus was written by someone who clearly

believed: (1)

that Jesus was a god;

(2)

that Jesus arose from the dead; and

(3) that Jesus was predicted by several Old Testament prophets. These were

the beliefs of those individuals who eventually came to be known as

Christians.

Josephus was an Orthodox Jew, not a Christian. He never converted to

Christianity. He, therefore, would not have made statements that would

only be made by a Christian. The above paragraph also states that the

Jews instigated Jesus' crucifixion. This was also a specifically Christian

idea. Since Josephus was not a Christian, it is unlikely that he would have

made this statement either

(see

Zeitlin 1928:

The Christ Passage in Josephus). It is, therefore, highly likely that the entire paragraph is a forgery (for an

extensive discussion of forgery in early Christian writing, see Ehrman 2013).

A less likely alternative would be to accept the paragraph as authentic, minus the lavender text (see

Mykytiuk 2015).

Josephus' description of Jesus stands in

sharp contrast with his discussion of John the Baptist, which is universally

accepted by biblical scholars as authentic. To begin with, Josephus'

discussion of John the Baptist contains 162 words, compared to only 60 words

about Jesus (Meier 1992: 227, note 8). Furthermore, unlike Josephus' reference

to Jesus, his description of John is largely invariant in all available

manuscripts of Antiquities.

In Addition, in contrast with Josephus' purported description of Jesus, the

vocabulary and style of the writing in his description of the Baptist are

consistent with that of the rest of

Antiquities

(see Meier 1992: 225-226). It is also significant that, while Josephus

presents a detailed discussion of the circumstances and popular beliefs

surrounding the execution of John (including the belief that Herod's army was

later destroyed as God's revenge for John's death), the above paragraph

contains at best a perfunctory mention of Jesus' execution.

In the second reference to

Jesus in Antiquities

(20.9.1), Josephus refers to Jesus in order to identify Jesus’ brother James,

the leader of the church in Jerusalem, who was executed by the high priest Ananus during the interregnum that occurred

in 62 CE between the death of the Roman

governor Festus and arrival of his replacement Albinus. Josephus

described the situation as follows:

Being therefore this kind of person [i.e., a heartless Sadducee], Ananus,

thinking that he had a favorable opportunity because Festus had died and

Albinus was still on his way, called a meeting [literally, "sanhedrin"] of

judges and brought into it the brother of Jesus-who-is-called-Messiah ...

James by name, and some others. He made the accusation that they had

transgressed the law, and he handed them over to be stoned.

The principal reason Josephus

mentions this incident is that Ananus' execution of James resulted in the

former losing his position as high priest.

Mykytiuk (2015: 4-5) explains why

Josephus includes a reference to Jesus in his description of that event.

James (Jacob) was a common Jewish name at this

time. Many men named James are mentioned in Josephus’s works, so Josephus

needed to specify which one he meant. The common custom of simply giving the

father’s name (James, son of Joseph) would not work here, because James’s

father’s name was also very common. Therefore Josephus identified this James

by reference to his famous brother Jesus. But James’s brother Jesus (Yehoshua)

also had a very common name. Josephus mentions at least 12 other men named

Jesus. Therefore Josephus specified

which

Jesus he was referring to by adding the phrase

"who is called Messiah,"

It is

significant that, in referencing Jesus during his discussion of the execution

of James, Josephus makes no mention that this is the same Jesus he described

previously in Antiquities.

As Zeitlin (1928: 235) clearly points out,

If these two passages, i.e. the

Christian passage and the James passage, really belong to Josephus, Josephus

in the second passage, where he says "James the brother of Christ," would have

said that

"this is the Christ who was crucified by

Pilate,"

as we see throughout his books that

where he has occasion to mention a name twice he repeats that "this is the

same man."

Significantly, an Old Russian translation of Josephus'

Jewish Wars

exists which diverges sharply from the Greek translation of that work. In it,

Josephus describes "an anonymous Wonder-worker, very much like Jesus, who was

associated with a projected attack on the Romans in Jerusalem, which the

latter anticipated and bloodily suppressed (Brandon 1967:368)." According to

Brandon (ibid.), the account of the teaching of the followers of this

Wonder-worker "accords remarkably with what we have been led to infer

concerning the teachings of the Jewish Christians."

Several researchers claim that Jesus may never have existed, arguing that

Jesus was a later mythical creation to serve the needs of a growing cult, as

were Zeus, Jupiter, Osiris, Mithras and the many other gods of the ancient

world (cf. Wells 1988; Price 2011; Carrier 2014; Carrier et.al. 2013). One

support for their claim is the absence of any clear extra-Biblical mention of

Jesus. The word

Christian is used only 3 times in the New Testament: twice in

Acts

(xi:26, xxvi:28) and once in

1Peter

(iv:16), but never in any of the gospels. It is

not until at least 40 years after Jesus' supposed death, he argues, that

any biographical material about Jesus emerges. The earliest New Testament

writings about Jesus are those contained in

Paul's Epistles.

Paul presents no biographical information about Jesus and very little hint

that Jesus was an actual human being. According to Wells, Paul makes no mention of Jesus'

birth, his crucifixion or of any other events in his life. What little

biographical information about Jesus does emerge, appears much later in the

various gospels and is both spotty and highly contradictory. Even the

claim that Jesus came from Nazareth is questioned and is considered by many

scholars to be a mistranslation of the word

Nazarite, which

refers to someone who has taken a vow to adhere to very strict Jewish

religious rules (see

Numbers. 6:2-21).

In fact, Nazareth may not have even existed in Jesus'

time. It is not mentioned anywhere in the Old Testament and does not

appear on any local maps until the second century CE. It is not

mentioned by Paul; nor is it contained in the Talmud, even though the Talmud

names 63 Galilean towns. Furthermore,

Josephus, who was the military leader placed in charge of Galilee during the

the revolt of 66-70 CE does not mention Nazareth in the list of towns he

visited in order to obtain recruits and supplies. At present, the

archaeological evidence for the earliest habitation of Nazareth are

inconclusive. Thus, little credible historical information exists from which a

reliable portrait of Jesus can be constructed, There is, therefore, some truth to

M.S. Enslin's (1961) comment on Jesus, "We do not have enough material to

write a respectable obituary."

8.

The early Christian Church was centered in

Jerusalem and was originally under the leadership of

James, the brother of Jesus

("Is this not the carpenter, the son of Mary and the brother of James and Joses and Judas

and Simon?" --Mark vi:3) (see also Matt.

xiii:55; Mark xvi:40; Gal. i:19; Acts xxi:18, xv:6-22). Paul was

not converted until about 34 CE, and by what he claimed was a divine

revelation. (The Uniformitarian Principle

in science would require that researchers treat the claim of divine revelation

by Paul using the same methods that would be applied to someone else making a

similar claim, whether today or in the past.) However, Paul's authority

was not accepted by James or by the members of Jerusalem Church. In

fact, Paul was strongly criticized and made to appear before James because of

the unacceptability of the version of Jesus that Paul taught (see Acts

xxi:20-26). While James did not recognize Paul's authority, Paul clearly

deferred to James.

Acts

of the Apostles

(xv:1-22; xxi:20-21) and the various epistles of

Paul clearly indicate that an intense conflict existed between

Paul and the leaders of the original Jerusalem Church

(see Abruzzi, The

Birth of Jesus, note #11). Paul and the

evangelists who later wrote the Gospels presented the

picture of a universalistic, non-Jewish messiah that was in sharp contrast

with the version of Christianity practiced by those who preached alongside

Jesus and who were eyewitnesses to his life. According to Paul, the members

of the Jerusalem Church taught a

"different Gospel" and presented

"another

Jesus" (Cor. II:4). While Paul taught of a Messiah to Jew and non-Jew alike,

the early apostles retained their Jewish orthodoxy. James was a respected

member of the Jewish community who closely adhered to Temple observances.

Moreover, the apostles were generally zealous in observing the dietary

regulations of the

Torah.

At one point Peter was rebuked by emissaries from James for eating among the

Gentiles while visiting Paul, and he subsequently

"withdrew from that place" (Gal. ii:11-12). When Paul was commanded to appear before James he was

expected to observe Temple (i.e., Jewish) rituals in order to demonstrate his

fidelity to the Jerusalem Church, and a major dispute occurred over

circumcision and the degree to which Gentile converts were expected to adhere

to Jewish law (see Acts xvi:3; xxi:18-26). Indeed, Barnabas, Paul's companion,

had to be circumcised on the spot before he and Paul would be allowed to

enter the Temple to meet with James.

Furthermore, members of the Christian

Church in Jerusalem included priests, Pharisees (Acts

vi:7, xv:5) and others who were described as

"zealous of the law" (i.e., the Torah) (Acts

xxi:20). With the total destruction of the Temple by the Romans in 70 CE and

the resulting devastation of Jerusalem, no trace remains of the original

Jerusalem Christian Church --the church founded by Jesus' apostles-- and its teachings. What little

may have been preserved, was either eliminated or edited by the later Gentile

Church leadership. Some scholars think that he descendants of the original Jerusalem Christian Church

crossed over into Jordan and later became known as the

Ebionites. The

Ebionites survived for about a century. Eventually, they were declared

heretics by the larger and more powerful Gentile Christian Church and

disappeared from history. (As an interesting side note, Martin Luther

purportedly so disliked the

Epistle of James,

which is generally attributed to James, the brother of Jesus, that he

regularly ripped it out of his Bibles.)

9.

Despite

editing, however, several accounts of Jesus' actions remain in the gospels which strongly

suggest that he taught a gospel in accordance with traditional Jewish notions

of a messiah and that he viewed himself as a prophet exclusively to the Jews.

To begin with, Jesus chose

12 apostles (not 10, 15

or 20). Twelve was an important number to the Jews: it represented

the mythical twelve tribes of Israel. Likewise, despite the presence of

many Gentiles (non-Jews) throughout Palestine, Jesus did not choose a single

Gentile as an apostle (or, for that matter a single woman). Indeed,

Jesus' parochialism is strongly evidenced by the fact that every one of his

apostles was a Galilean. Not one apostles even came from Judea or

Samaria. In addition, Jesus and his apostles preached only among the

Jews, and they never preached outside of Palestine, an area the size of New

Jersey (see map below).

Also, when

Peter asks Jesus, "We have left everything to

follow you! What then will there be for us?",

Jesus replies, "I tell you the truth, at the

renewal of all things, when the Son of Man sits on his glorious throne, you

who have followed me will also sit on twelve thrones, judging the twelve

tribes of Israel." (Matthew ixx:27-28)

In other words, Jesus' mission is to the Jews --i.e., to the Twelve Tribes of

Israel.

Finally, in the

Synoptic Gospels (Mark,

Matthew and Luke) Jesus is always pictured adhering to all the tenets of

Judaism. In Matthew (v:17) Jesus says

"Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the prophets. I come not

to abolish but to fulfill." In Matthew

(x:5-6) Jesus commands his apostles: "Go

nowhere among the Gentiles, and enter no town of the Samaritans; but go rather

to the lost sheep of the house of Israel." In

Matthew (x:34-35) he also states: "Think not

that I come to send peace on earth: I come not to send peace but a sword.

For I come to set a man at variance against his father, and the daughter

against her mother, and the daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law."

Again in Matthew (x:38) he says, "And whoever

does not take up the cross and follow me is not worthy of me."

And yet again in Matthew (x:14-15) Jesus states:

"If anyone will not welcome you or listen to your words,

shake off the dust from your feet as you leave that house or town. Truly

I tell you, it will be more tolerable for the land of Sodom and Gomorra on the

day of judgment than for that town."

|

Jesus'

initial refusal to heal the daughter of the "Syrophonecian woman" (Mark

vii:24-30; Matthew xv:21-28) was based on her being a Gentile, and he

resorts to calling her a "dog",

a derogatory term applied by Jews to Gentiles at that time:

"Let the children be fed first, for it is not fair to

take the children's food and throw it to the dogs" (Mark

vii:27;

see Abruzzi, The

Birth of Jesus, note #11) Jesus eventually agrees to cure the woman's daughter,

but only after she demonstrates her subservient status as a Gentile:

"But she answered him, 'Sir, even the dogs under

the table eat the children's crumbs'" (Mark

vii:28; see also Matthew xv:27). Similarly, he instructs his apostles

to "Do not give what is holy to dogs; and do

not throw your pearls before swine." (see

Matthew vii:6). The term swine (pig) was a derogatory term used by the Jews of the time to refer to Roman

soldiers (much as anti-war demonstrators of the 1960's used the same term to

refer to the police).

Jesus'

clearing of the Temple was in the militant tradition of Jewish resistance

groups like the Zealots and the

Sicari in that it threatened the economic

base of the religious aristocracy (the Sadducees) who helped maintain Roman

rule. This was

likely the reason that religious leaders arrested Jesus. Some scholars

also argue that Jesus could not

conceivably have cleared the Temple alone and unaided (anymore than a single

person today could clear an entire shopping center by themselves). Indeed,

those in charge did not try to arrest him at the time because they feared the

wrath of the crowd (Mark xxii:12). They arrested him later in the evening

instead when it was safer to do so. |

|

|

Significantly, the cleansing of the temple occurred

shortly following Jesus' grand entrance into Jerusalem among a cheering crowd

shouting

"hosanna", a term which had a political meaning at the time (Brandon

1967), and in a manner according to which earlier Jewish prophets claimed the

Messiah-king would come to restore Israel's freedom.

Coincident with Jesus' entrance into Jerusalem and his skirmish at the Temple,

an attack was made against the Roman garrison. It was during that attack (in

which several Roman soldiers were killed) that

Barabbas was apparently

arrested. Some scholars believe that the two events were connected. In any

case, later that night anticipating his arrest on the Mount of Olives, Jesus

made sure his apostles were armed (Luke xxii: 35-38).

10.

In the earlier gospels,

Jesus is also clear when the day of judgment was to occur. As he sent his

apostles out he said: "And as you go proclaim the good news, "The kingdom of

heaven has come near." (Matthew x:7) "But when they persecute you in one

town, flee to the next; for truly I tell you, you will not have gone through

all the towns of Israel, before the Son of Man comes." (Matthew x:23). In

Luke (xxi:32), Jesus says: "Truly I tell you, this generation will not pass

away until all things have taken place." It is only later, with the writing

of the Gospel of John (by which time Jesus had not returned) that an explicit

reference to the time of the second coming is dropped. It is for this

reason that most scholars view Jesus as an

eschatological prophet who, like John the Baptist

and numerous others at the time, preached that the end of the world was at hand (cf.

Ehrman 1999).

This picture of Jesus is presented very clearly in Mark and in Matthew.

However, in the later gospels the picture of Jesus changes; since the events

that Jesus forecasted did not occur, the timing of the Second Coming becomes

increasingly indeterminate.

11.

Like all written documents, the Bible has

undergone numerous changes during the past 2,000 years. It has, first of all,

undergone numerous translations and revisions. In the past 100 years,

archaeological discoveries at

Qumran

in Palestine, at

Nag

Hammadi

in Egypt

and elsewhere have uncovered many Christian and pre-Christian documents that

were destroyed and were, therefore, eliminated from the Christian record

(particularly as those referred to today as the

Orthodox faction gained control of the Church during

the fourth century CE). Over 50 documents were discovered at Nag Hammadi

alone, including gospels by Thomas, Peter, James (Jesus' brother), Mary

Magdalene and Philip (see Pagels 1981; Barnstone 1984; Robinson 1988).

The discovery of these documents forced hundreds of changes in the

King James Version

of the Bible and has spawned the creation of whole new versions of the Bible,

including the

New Jerusalem Version

and the

New

Revised Standard Version.

As a result of these discoveries, the King James Version is now considered a

highly inaccurate (though beautifully written) version of the Bible.

Significantly,

the Gnostic Gospels present a very different picture of Jesus and of

the relation of Mary Magdalene and the Apostles to Jesus. Mary is

variously referred to in the

Gnostic Gospels

as the "One who knew the All", the "Apostle who excels the rest", the

"Disciple of the Lord", "One who reveals the Greatness of the Revealer", the

"Inheritor of the Light", the "Privileged Interlocutor", the "One who is

always with the Lord", the "One whom they call His Consort", and the "Chosen

of Women".

The

Gospel

of Philip

even

states:

“The Lord loved Mary more than all the disciples and kissed her on her

mouth often. The others said to him: Why do you love her more than all of

us? The Savior answered and said to them: Why do I not love you like her?”

The

Gospel of Mary

discusses the jealousy of the apostles towards her and of her conflict with

them (especially Peter) due to the closeness of her relationship with Jesus.

It is the "special relationship" between Jesus and Mary Magdalene

presented throughout the

Gnostic Gospels

that has provided the basis for the claim that Jesus and Mary were married

made in such popular books as

Holy Blood Holy Grail

and

The DaVinci Code.

Those who claim

that Jesus and Mary

Magdalene were married argue that, given Jewish customs during the first century

CE, it is unlikely that a single woman could have traveled alone with Jesus

without creating a controversy. Some have even suggested that the

wedding feast at Cana was Jesus' wedding. Why, they ask, would servants

have come to guests at a wedding to tell them they are out of wine? More

likely, the servants would have gone to the groom and to the family giving the

wedding to inform them of the situation in order to find out what to do.

Finally, all four canonical gospels list Mary Magdalene as the first person at

Jesus' tomb and the one who discovered his body missing. She was the

original disciple of the risen Jesus --the

Apostle to the Apostles.

Much of the censorship of the New Testament occurred during

the third and fourth centuries CE as Christianity became an established state

religion within the Roman Empire. In 313 CE, Constantine issued the

Edict of Milan,

which forbade persecution of all forms of monotheism, including Christianity.

Constantine, who converted to Christianity on his deathbed, also presided over the

Council

of Nicea

in 325

CE, at which time three principles were established as central tenets of

Christianity:

(1) the divinity of Jesus,

(2) Jesus' virgin birth, and

(3)

Jesus' physical resurrection. These principles were established by a vote of

those who attended the Council and incorporated into a document known as

The Nicene Creed. This date, thus, marks the effective

beginning of modern Christianity.

The Council of Nicea and The Nicene Creed were a

response to the fact that there were many Christian denominations that

rejected one or more of these three principles, including

Gnostic

Christians.

These Christians referred to the more conservative form of Christianity based

on the above three principles as the "faith of fools" for accepting such

absurd ideas (Pagels 1981). To the Gnostic Christians, these three principles

were to be understood as referring to the spiritual aspect of Jesus; they were

not to be taken as literal statements (much as fundamentalist Christians today

accept the literal interpretation of the Bible). The acceptance of these three

principles as fundamental Christian beliefs marked the political victory of

the orthodox and literalist faction within the early Church. With the

power of Rome on the side of the orthodox faction (governments tend to side with

orthodox conservatives rather than free-thinking liberals), all opposing

forces, especially the Gnostics, were branded as heretics and eliminated.

However, numerous dissenting groups arose within

Christianity during the following centuries that rejected the three basic

principles mentioned above. These were routinely defined as heretics and

forcefully suppressed by the Church because they represented threats to its

authority and power. The most notable of these groups were the

Albigensians

(Cathars)

of southern France against which the Church launched one of its holy wars or

Crusades, comparable to a Muslim

jihad. (Many

characteristics associated with the Christian Crusades were similar to those

of the the Muslim jihad [holy war], including the proclamation that those who

died in battle would go directly to heaven.)

Finally, in 331 CE, Constantine commissioned the compiling

of the

New Testament

(The Christian Bible). In 367 CE, Bishop Athanasius of Alexandria compiled a

list of books to be included in the New Testament. His list was eventually

ratified by a Church council at Hippo in 392 CE and again by the Council of

Carthage in 397 CE. Early Christian writings that did not conform to the

orthodox view of Christianity --of which there were many (see Pagels

1981; Barnstone 1984; Robinson 1990) -- were

destroyed, while parts of New Testament documents (including sections of the

four canonical Gospels) that did not adhere to the dominant view were

removed. (The

Gospel of John,

for example, was very controversial and was initially rejected by many

orthodox bishops as being non-canonical. It was considered too Gnostic.

Similarly, as mentioned above, the original Gospel of Mark did not include a

resurrection.) It was in this manner that the New Testament came to be what

it is today. As Pagels (1981:179) clearly notes,

"It is the winners who write

history --their way."

Of the nearly 5,000 early manuscript versions of the New Testament, not one

predates the 4th century CE. It is only with the discoveries at Qumran

and Nag Hammadi that many of the early documents destroyed during the fourth

century have been recovered, giving us a fresh new look at early Christianity.

Asimov, Isaac. (1991).

Asimov's Guide to the Bible: The New Testament.

Wings Books.

Brandon, S.G.F. (1967).

Jesus and the Zealots: The Study of the Political Factor in Primitive

Christianity.

New York: Charles Schribner's Sons.

Brandon,

S.G.F (1968).

The Trial of Jesus of Nazareth.

New York: Stein and Day.

Barnstone, Willis (ed.).

(1984).

The Other Bible: Jewish

Pseudepigrapha, Christian

Apocrypha, Gnostic Scriptures.

New York: Harper and Row.

Carrier, Richard. (2014). On the Historicity of

Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press.

Carrier, Richard, D.M. Murdock, Earl Doherty,

Ren Salm, David Fitzgerald, Frank R. Zindler, and Robert M. Price. (2013).

Bart Ehrman and the

Quest of the Historical Jesus of Nazareth: An Evaluation of Ehrman s Did Jesus

Exist?

Cranford, NJ:

American Atheist Press.

Crossan,

John D. (1992).

The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant.

San Francisco: Harper Collins.

Davies,

A. Powell. (1956).

The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

London: Penguin.

Ehrman, Bart. (1999).

Jesus.: Apocalyptic

Prophet of the New Millennium.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ehrman, Bart. (2007).

The New Testament: A Historical

Introduction to the Early Christian Writings.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ehrman, Bart,. (2013).

Forgery and Counterforgery: The Use of

Literary Deceit in Early Christian Polemics.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eisenman, Robert. (1997).

James: The Brother of Jesus.

New York: Penguin Books.

Eisenman, Robert. (1993).

Dead Sea Scrolls Uncovered. New York: Penguin

Books.

Enslin, M.S. (1961).

The Prophet of Nazareth.

New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fox,

Robin L. (1992).

The Unauthorized Version.

New York: Knopf.

Fredrikson, Paula. (2000).

From Jesus to Christ: The Origin of New Testament Images of Jesus.

New Haven: Yale University Press.

Friedman, Richard Elliott. (1987).

Who Wrote the Bible?

New York: Harper and Row.

Funk, Robert, Roy

Hoover and the Jesus Seminar. (1996).

The Five Gospels: What Did Jesus Really Say?

San Francisco: Harper.

Harris, Marvin. (1974). "Messiahs", and

"The Secret of the Prince of Peace." in

Cows,

Pigs,

Wars and Witches.

New

York: Random House.

Horsley, Richard and

John Hanson. (1985).

Bandits, Prophets, and Messiahs: Popular

Movements at the Time of Jesus.

San Francisco: Harper and Row.

Meier, John P. (1992). John the Baptist

in Josephus: Philology and Exegesis.

Journal of Biblical Literature

111(2): 225-237

MyKytiuk, Lawrence. (2015). Did Jesus

Exist? Searching for Evidence Beyond the Bible. In Robin Ngo and Megan Sauter

(eds.).

Who Was Jesus? Exploring

the History of Jesus' Life.

Biblical Archaeology Society.

Pagels, Elaine (1981).

The Gnostic Gospels.

New York: Random House.

Price, Robert M. (2011).

The Christ-Myth Theory and

Its Problems.

Cranford, NJ:

American Atheist Press.

Robinson, James M. (ed.). (1988).

The Nag Hammadi Library.

New York: Harper and Row.

Samuelsson, Gunnar. (2011).

Crucifixion in Antiquity: An Inquiry

into the Background and Significance of the New Testament Terminology of

Crucifixion.

Tübingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck.

Stanton, G.N.. (1989).

The Gospels and Jesus.

London: Oxford University Press.

Vermes, Geza. (1973).

Jesus the Jew: A Historian's Reading of the Gospels.

Philadelphia:

Fortress Press.

Vermez, Gaza. (2006).

Who's Who in the Age of Jesus.

Penguin Books.

Wells. G.A. (1988).

The Historical Evidence for Jesus.

Buffalo: Prometheus Books.

Wilson, A.N. (1992).

Jesus: A Life.

New York: Norton.

Wilson, W. R. (1970).

The Execution of Jesus: A

Judicial, Literary and Historical

Investigation.

New York: Scribner's Sons.

Zeitlan, Solomon. (1967).

The Rise and Fall of the

Judean State: A Political, Social and Religious History of the Second

Commonwealth, Volume Two: 37 B.C.E. - 66 C.E.,

Jewish Publication Society of America.

Zeitlin, Solomon. (1928). The Christ

Passage in Josephus.

The

Jewish Quarterly Review,

18(3): 231-255.

Zindler, Frank R. (1998).

"Did Jesus Exist?"

The American Atheist,

(Summer Issue).

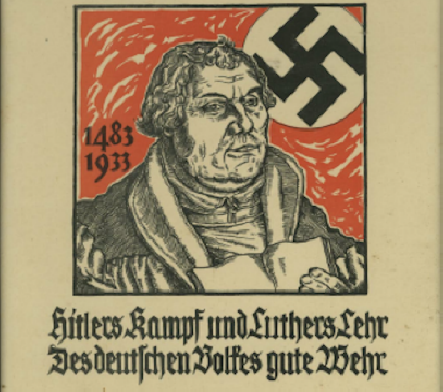

* *

* * *

Of Related

Interest:

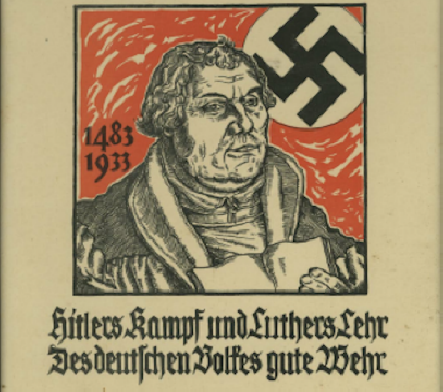

Martin

Luther

Hero

and Inspiration to the Nazis

.jpg)

The Date of Jesus' Birth

.jpg)

Mithraism and Christianity

Bill O'Reilly is Killing Jesus

* *

* * *

|

|

|

Body Piercing Saved my

Soul! |

|

|

Jesus Beat the Devil with Two

Sticks! |

|

* *

* * *

Home

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)