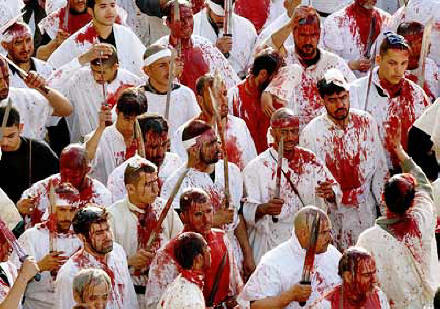

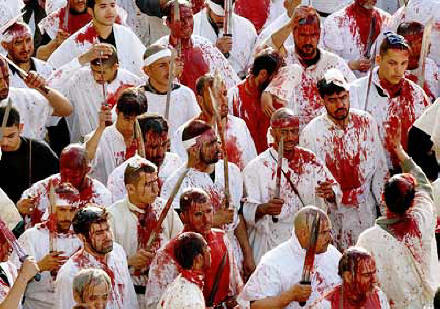

Ashoura

Below are several pictures of men in Iraq, Syria and elsewhere celebrating Ashoura, the holiest day of the Shiite Muslim calendar. Ashoura marks the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Mohammed, in a 7th century battle for leadership of the Islamic world. Pilgrims flagellate themselves with chains and cut themselves with swords in grief at Hussein's death.

The 61 AH (680 CE) battle in the desert plain around Karbala, Iraq was a defining moment in the split between Islam's Sunni and Shiite sects. Hussein's father, Imam Ali, had been killed 20 years earlier, and leadership of the Islamic community was taken by the Sunni Ummayad dynasty. But Ali's followers, the Shiites, rallied behind his son.

Hussein and his followers moved from the Arabian peninsula into Iraq, harried by forces of the Ummayad caliph Yazid. Finally, Hussein was left with only a handful of supporters, surrounded by Ummayad forces.

On the 10th day of the Muslim month of Muharram, the Ummayads attacked the band. Hussein and the men with him were decapitated, and the women taken prisoner.

Leadership of the Shiites was then passed down through a series of imams. The seventh and ninth imams, Mousa Kadhem and Muhammad al-Jawad, are buried at the Kazimiyah shrine in Baghdad, which was one of the sites attacked Tuesday.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* * * * *

The following article from The Economist gives some historical background on the relationship between Shia and Sunni Muslims, thus indicating the importance that the Ashoura ritual plays in Shiite political identity.

The History of Shia Muslims

Why the aggravation?

The Economist

Mar 4th 2004 | Cairo

Bad blood did not always flow between Sunnis and Shias

“BETTER sixty years of tyranny than one day of fitna.” The term in the Arabic saying refers to civil strife, particularly the kind caused by religious schism. Not only is fitna a calamitous sign of the coming day of judgment; it also reflects fears deeply embedded in Muslim memory. The schism between Sunnis and Shias in the early centuries of Islam was blamed for blunting the new religion's expansion. Later, it was blamed for weakening Muslims in general, and for opening the way to invasion by infidel hordes.

|

Few mention such things now, but long ago a communistic Shia sect raided Mecca, stole the sacred Black Stone, and held it hostage for 22 years before returning it, broken in pieces. Shia dynasties once ruled Tunisia, Egypt and the eastern end of the Mediterranean. Their overthrow by orthodox Sunnis was seen by them as a greater triumph than the defeat of the Crusaders. And of course Ashoura, the day of martyrdom celebrated last week, commemorates Shia suffering at the hands of Sunnis.

Yet for the last 800 years or so, sectarian divisions have lain mostly dormant. Shias tended to live in isolation and on the margins—in the mountains of Lebanon and Yemen, on the hot, swampy shores of the Persian Gulf, in self-contained Indian trading communities. In Iran, where they formed a majority, Shiism overlapped with and reinforced an exclusive Iranian national identity. Neither Sunnis nor Shias knew or cared much about their cousins. Few challenged the Sunni assumption of superiority, while the Shias, with their doctrinal emphasis on martyrdom and victimhood, thrived on their own marginalisation. |

Prostrate outside Ali's shrine in Najaf |

Urbanisation, migration and the imposition of national borders have brought the sects into renewed proximity. Mostly, the mixing has been painless. For decades, city-dwelling Sunnis and Shias in Beirut and Baghdad happily intermarried. Forty years ago, Egypt's leading cleric of the time even declared mainstream Shiism to be an accepted branch of the faith. But other strains of Sunnism have been less tolerant.

The puritan revival known as Wahhabism has, since its beginnings in Saudi Arabia, been particularly hostile to Shiism. In the early 19th century, Wahhabi raiders sacked Shia shrines in Mecca, Medina and Karbala, accusing their keepers of worshipping idols. Saudi Arabia still denies many rights to its large Shia minority, and vilifies it in school textbooks.

Wahhabism has strongly influenced modern Sunni militant movements, including Afghanistan's Taliban, radicals in Pakistan, and some components of Osama bin Laden's al-Qaeda. On the morning of this Ashoura, for instance, a Kuwaiti sheikh, Hamed al-Ali, posted on his website a letter condemning the rite as “the world's biggest display of heathens and idolatry”. He accused Iraq's Shias of plotting to assassinate Sunni leaders, foment strife across the region, grab the Gulf's oil, and form an evil axis linking Washington, Tel Aviv and the Shia holy city of Najaf.

Even more poisonous vitriol appears in a letter that American intelligence attributes to the alleged leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq, Abu Musab al Zarqawi. The Shias, he says, are a more pernicious enemy than the Americans, and the best strategy for the poor, weak and sleepy Sunnis is to “strike their religious, military and other cadres”—in other words, to stoke fitna so as to preclude the transfer of power to a Shia-dominated democracy.

Yet many Muslims, including Iraqi Shias, shy away from accepting that fellow Muslims could commit so heinous a crime as this week's slaughter. Hassan Nasrallah, the charismatic leader of Hizbullah, the Lebanese Shia militia, declared that the main beneficiaries of the attacks were America and Israel. Yet, he added, if it turned out that the perpetrators were “petrified extremists living in the stone age who claim allegiance to Islam”, then this was a far sadder and greater danger.

* * * * *

Christians, most notably Roman Catholics, have also practiced flagellation. Flagellantism was a penitent movement that arose in Italy in the 13th century and spread across Europe during the 14th century. The self-flagellation movement originated in response to a famine in Italy and was practiced by Christians in response to the Black Plague of the 14th Century and other calamities.

|

|

|

Although flagellation was eventually condemned by the Church, it has persisted down to the present, most notably in Spain, Italy and former colonies, such as the Phillipines. It is today most commonly practiced as part of a Holy Week reenactment of the Roman crucifixion of Jesus.. It was even practiced in the U.S. in northern New Mexico by the lay religious brotherhood, Los Hermanos Penitentes until the practice was condemned by the Roman Church in the late 19th century following U.S. acquisition of the territory after its war with Mexico.

Holy Week Flagellation Ritual in the Philippines

|

|

|

|

|

|

More recently, both Pope John Paul II and Mother Teresa practiced self-flagellation.

|

|

|

* * * * *