Circumcision, Subincision

and Other Forms of

Ritual Genital Surgery

(including what is generally referred to as "Female Genital Mutilation")

* * * * *

An

Anthropological Perspective

William S. Abruzzi

(2008)

A Maasai male must show no pain while being circumcised

1. Various forms of ritualized genital surgery --circumcision, subincision, infibulation and emasculation-- are practiced throughout the world today and have been practiced by many peoples throughout history. Those who practice ritualized genital surgery range from peoples living in small hunting and gathering bands using very simple technology to those living in complex technologically sophisticated societies such as the United States. As an intellectual discipline, anthropology is concerned with attempting to understand and explain the practice of ritualized genital surgery from a rational, scientific perspective in the same way that it attempts to explain all other forms of human behavior. Anthropology is NOT concerned with making ethnocentric moral judgments about the various forms this behavior takes. Rather, it is concerned with testing and evaluating the different explanations proposed to explain this behavior in all its various forms.

2. Certain specific forms of genital surgery, including circumcision, infibulation and subincision, are frequently performed in conjunction with rites of passage marking the transition of individuals from childhood to adulthood within their local communities. Throughout Africa, genital surgery is generally performed at the end of a period of seclusion, after which the initiates emerge as adults in their society, prepared not only to receive the benefits of being an adult, but also the expectations and responsibilities associated with becoming an adult. In the past, the period of seclusion may have lasted several weeks or even several months. More recently, however, due to changes in economic and social conditions, the period of isolation is likely to be shorter, in many cases lasting only a few days. It is during the period of isolation that the initiates (both boys and girls) receive formal training in what will be expected of them once they become adults. The interesting question from an anthropological perspective is why so many societies would mark the transition from childhood to adulthood with a ritual involving genital surgery. What social factors would make sense of this practice? How might those societies that perform ritual surgery differ from those that do not?

|

3. Societies throughout the world differ with regard to the age at which ritualized genital surgery is performed. While some peoples, including Jews and Americans, perform the ritual following birth, others, including most of the peoples who practice it in Africa, perform the ritual surgery during puberty. One question of interest to anthropologists is why different societies institutionalize the practice of ritualized genital surgery at different times in an individual's life cycle. Might it be related to the different role the ritual plays in the life cycle of individuals in those societies? |

Circumcision in the U.S. |

4. Peoples throughout the world also differ with regard to which individuals are expected to undergo ritualized genital surgery. Americans, Jews and many other societies circumcise only male children. Other societies, most notably in Africa and the Middle East, perform ritualized genital surgery on both males and females. Very few societies perform ritualized genital surgery exclusively on females. Why would the sex of the individual experiencing ritualized genital surgery differ from one society to the next, and why would males be circumcised far more commonly than females? Could the structure of adult gender relations in a particular society influence which sex is circumcised in that society? Do, for example, those societies that perform ritualized genital surgery on both sexes display different gender relations than those that perform it on only one sex? Might the gender relations in those societies that perform ritualized genital surgery on both sexes be more egalitarian than those that do not, or could they be more competitive?

5. Many of the peoples who practice circumcision, subincision, female circumcision and infibulation claim that they do so for health reasons. Most Americans also believe that male circumcision in the U.S. is practiced primarily for medical reasons. Are these beliefs correct? Does David Gollaher's article on the history of male circumcision in Europe and the U.S. support such a belief? What about P M Fleiss, F M Hodges, R S Van Howe's article on immunological function of the human foreskin? If these articles do not support the popularly accepted view of the medical benefits of male circumcision in the U.S., then does it make sense for Americans to criticize other people for practicing genital surgery for "medical" reasons while condoning the same practice at home? Some individuals claim that there is a reduced incidence of penile cancer among circumcised males compared to uncircumcised males (a claim which is not supported by scientific research). Even if it were true, would this be a logically valid reason to perform male circumcisions? Penile cancer in the U.S. occurs in about one out of every 100,000 males in the population. Moreover, it occurs primarily among elderly men. Is it reasonable, then, to practice the routine circumcision of all males if only an extremely small minority of males ever contracts penile cancer? Wouldn't the removal of any part of the body --the arm, leg, hip, lung or breast-- result in a reduction in the incidence of cancer in that body part? Wouldn't it be just as logical to justify routine mastectomies for all young girls in order to prevent breast cancer which, after all, is far more common and more lethal than penile cancer? As Gollaher (2000:145) states in his book, Circumcision: A History of the World's Most Controversial Surgery,

"In any case, the evidence is conclusive that circumcision prevents penile cancer just as mastectomy prevents breast cancer. Removing one third to one half of the skin of the penis lowers the odds of contracting what is, after all, a skin cancer. A high percentage of skin cancers eventually develop on the nose, one dermatologist noted; but this has not led physicians to recommend prophylactic rhinoplasties."

|

6. Many peoples in Africa and elsewhere claim that they practice circumcision (male and female) for aesthetic reasons. To them, the uncircumcised penis or vulva is considered unattractive. Are Americans any different? To what extent is the uncircumcised penis considered less attractive in the U.S.? (The author of one article in the New England Journal of Medicine concluded that "circumcision is a beautification comparable to rhinoplasty.") Indeed, many medical health plans, including Blue Cross and Blue Shield, no longer cover circumcision, defining it as cosmetic surgery. Aesthetics are socially acquired, and people learn to appreciate and value that which is appreciated and valued by others around them. Most Americans view the circumcised penis as more attractive simply because it is what is most common. Why would one expect Africans and others to be any different? Indeed, no country on earth spends more money altering the form of the human body for purely aesthetic reasons than does the U.S. It seems rather inconsistent for Americans to criticize other peoples for performing surgery to "improve" the appearance of their bodies and their children's bodies at the same time that such behavior has created a multi-billion dollar industry in the U.S. (see Pretty Poison) |

Silicon Breast Implant |

Interestingly enough, genital surgery is increasingly being done in the U.S. on both men and women, though mostly on women. Significantly, the most popular forms of genital surgery requested by women are vaginoplasty (the tightening of the vaginal muscles) and labiaplasty (the surgical reduction of the labia minora). This latter surgery is essentially the same procedure as excision, the most common form of circumcision performed on women in Africa. According to the American Association of Plastic Surgeons, the doctors who perform these surgeries are paid from $3,500 to $8,000 per surgery. Furthermore, the principal reason women choose to have these vaginal surgeries done is their concern with the “aesthetics of the vagina,” due in part to such fashion influences as flimsier swimsuits, as well as to increasing exposure to nudity in magazines and films.

|

Body Mutilation American Style

2. Liposuction

Given the popularity of the above procedures, it would seem rather disingenuous for Americans to criticize other peoples for their body modification practices.

|

7. In addition to the routine practice of ritualized genital surgery in the form of circumcision, infibulation and subincision, many societies have tolerated and even encouraged radical genital surgery involving the complete removal of an individual's genital organs. In India, for example, many men undergo an emasculation ritual that turns them into Hijras, a caste of eunuchs (neither men nor women) that perform Hindu rituals at such rites of passage as weddings or the birth of a male child. Many imperial courts throughout history have maintained eunuchs to guard a ruler's harem or to serve as an advisor to a king. Even the Roman Catholic Church at one time encouraged and sanctified castration. Many families in Europe offered castrated sons to the Church to perform in Church choirs. Many of these castrati eventually became well known performers throughout Europe. Even our own society accepts and practices radical genital surgery. Formal procedures have been established in most states by which individuals may undergo surgery to change their sex. Depending on which direction the change occurs, such procedures involve hormone therapy, breast elimination or augmentation, pectoral surgery, the removal or construction of a penis and the elimination or creation of a vaginal cavity. The city of San Francisco has even recently included sex change operations as part of the health benefits package it provides for its employees. Significantly, not only have all of the more radical forms of genital surgery described above been performed on males, but so also have the overwhelming majority of sex change operations been performed on males.

Also, circumcision is but one form of bodily mutilation that has been practiced throughout the world. A whole array of bodily transformations may be performed during rites of passage signifying significant changes in social status. including ritual hair cuttings, knocking teeth out, amputating fingers, tattooing, scarification, perforating, stretching and inserting plates or other objects in either the earlobes, septum or lips. Focusing on just circumcision --especially just female circumcision-- without considering all the various forms of bodily alterations that accompany changes in an individual's social status among the many societies of the world, seriously restricts and biases any understanding of the social role that these rituals perform. The important social role of these body mutilation rituals was made clear by Bronislaw Malinowski, an anthropologist describing male initiation rituals among the Trobriand Islanders over 50 years ago.

"The novices have to undergo a more or less protracted period of seclusion and preparation. Then comes initiation proper, in which the youth, passing through a series of ordeals, is finally submitted to an act of bodily mutilation: at the mildest, a slight incision or the knocking out of a tooth; or, more severe, circumcision; or really cruel and dangerous, an operation such as subincision. . . . The ordeal is usually associated with the idea of death and rebirth of the initiated one, which is sometimes enacted in a mimetic performance. But besides the ordeal, less conspicuous and dramatic, but in reality more important, is the second main aspect of the initiation: the systematic instruction of the youth in sacred myths and tradition, the gradual unveiling of tribal mysteries and the exhibition of sacred objects."

--B. Malinowski, Magic, Science and Religion (1948)

|

Krono girls celebrating their circumcision |

It is important to consider the social factors that would lead not only to the acceptance of radical genital surgery in a society, but also to its institutionalization? Why would some men in India be willing to undergo the complete loss of their sexuality? What factors would lead many parents in Europe to be willing to have their sons castrated in order to perform in Church choirs? Why would so many men in the U.S. be willing to undergo surgical sexual reassignment? Why would some societies not just condone such practices, but actually institutionalize them? Why are such practices frequently associated with religious beliefs and practices? Can we better understand these behaviors by viewing them within the context of the gender relations that prevail in various societies and, thus, in terms of the underlying economic, social and political conditions that create those gender relations? Also, is it significant in this regard that the overwhelming majority of radical genital surgery performed to either eliminate or change sexual identification in different societies has been performed on males? |

8. In his comparison of male and female circumcision, Boyd (Circumcision Exposed) describes many similarities between these two practices. Both male and female circumcisions, according to Boyd, diminish sexual sensitivity, are forced on children without their consent and are justified through recourse to hygiene, religion and/or tradition. Yet, only female circumcision is opposed in the West, particularly in the U.S. Furthermore, female circumcision is opposed in the West with considerable emotion, polemics and accusations regarding the patriarchal exploitation of women. Why does such strong and vociferous opposition exist to female circumcision by the same people who accept and practice male circumcision and who may even employ many of the same rationalizations for condoning male circumcision that other societies employ to justify female circumcision? Are such people acting rationally? Are they applying a consistent logic to both of these practices, or are they applying separate standards for the different social behaviors? The principal difference that Boyd illustrates in his comparison of male and female circumcision is that only the male circumcision is practiced in the U.S., while only female circumcision is opposed in the U.S. To what extent does Western opposition exclusively to female circumcision simply reflect Western ethnocentrism?

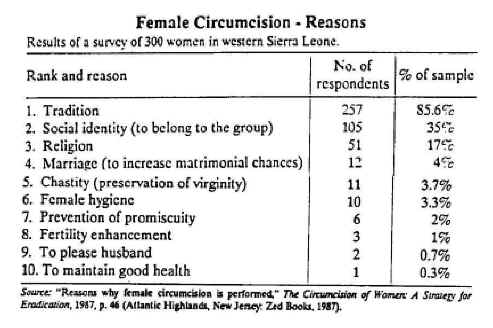

Baby strapped to restraint during circumcision in hospital

9. Several reasons have been given by various authors for why female circumcision is practiced, including religion, control over a woman's sexuality and pleasing a woman's husband or the husband-to-be. Do the authors who make these claims present sufficient data to support their statements that these are, in fact, the reasons that the procedure is performed? If not, do the available data support their claims? What reasons do the people themselves give for why they practice this ritual? A survey of 300 women in Sierra Leone (see chart below) showed that the overwhelming reason that women practiced circumcision was simply "tradition", in other words, because it was the norm. "Pleasing the husband", "maintaining chastity" and other reasons that have been claimed most commonly in the West were insignificant by comparison (see Table below). In making statements about why female circumcision is practiced, do the various authors distinguish between emic and etic explanations, or do they confuse the two kinds of explanations? How might their confusing emic and etic explanations interfere with their gaining a systematic understanding of the causes underlying the existence of this practice?

10. It is also interesting in this light to explore the origin of circumcision in the U.S. Contrary to generally accepted opinion, circumcision did not originate in the U.S. as a result of scientific research showing its medical advantages. Rather, circumcision emerged during the public health movement of the late nineteenth century. It was seen at the time as the personal hygienic complement to improved community health standards. Male circumcision was promoted as either a cure or a preventive procedure for a wide variety of ailments, including hernia, epilepsy, polio, cancer, syphilis and lunacy. One of the studies that contributed to the circumcision movement was an 1890 epidemiological study of American Jews. This study observed that death rates were lower among the Jews, that the Jews had fewer still-born children and that Jews had a greater average longevity. This was all attributed to the fact that the Jews practiced male circumcision. Typical of comments at the time, Norman Chapman, a professor of nervous and mental diseases at the University of Kansas City, stated in Medical News in 1882 that "Moses was a good sanitarian . . . and if circumcision was more generally practiced at the present day, I believe we would hear far less of the pollutions and indiscretions of youth; and that our daily papers would not be so profusely flooded with all kinds of sure cures for loss of manhood." Peter Remondino, an ardent proponent of male circumcision, went so far as to claim that "life-insurance companies should class the wearer of the prepuce under the head of hazardous risks." (Chapman and Remondino quoted in Gollaher).

Female circumcision and ovariotomy were both introduced and experimented with at the same time as male circumcision. They too were promoted as cures for a variety of ailments, including hysteria, neurasthenia and backache. However, unlike male circumcision, which were far more widespread and were eventually extended to the majority of the male population, clitoridectomies were never performed on more than a very small minority of women. The expansion of circumcision to the general male population was achieved primarily by promoting it for patients who could not resist and who could also be restrained rather easily. --infants. This was achieved rather easily. Routine infant male circumcision was promoted by medical authorities as one way of reducing infant mortality, which was responsible for up to 25% of infant deaths at the time. And the full weight of medical authority came down on the side of male circumcision. One publication in 1912 went so far as to state that "parents who do not have an early circumcision performed on their boys are almost criminally negligent" (Lydston quoted in Gollaher). Thus, without any research to substantiate such claims (or the many other claims made in favor of male circumcision), this procedure became the accepted norm.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

|

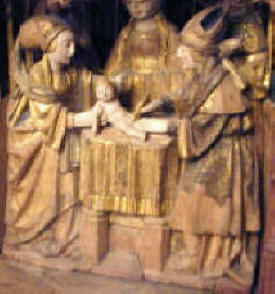

To the right is a relief depicting Jesus' circumcision. It is part of the screen built to house the choir at Chartres Cathedral in France. To the left are Mary and Joseph, who have brought their newborn son to the Temple in order to have him circumcised. Notice that Mary is holding a cloth which she has extended in order to catch the child's foreskin. This relief was included in the choir because Chartres was one of several churches that claimed to possess Jesus' foreskin, which at the time was considered a sacred relic (The Holy Prepuce). Chartres also claims today to possess the birth cloth of Jesus (below).

|

The Circumcision of Jesus |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

11. Many of those who oppose female circumcision in Africa and elsewhere claim they do so because of the medical complications associated with this procedure. However, medical complications occur with male circumcisions as well, including circumcisions performed in the U.S. under the most sanitary conditions, as shown by the photos below (see also Circumcision Surgery Accidents, Complications, and Atrocities). Is female circumcision more hazardous than male circumcision? Do the differences between the African data and the U.S. data reflect a difference between male and female circumcision per se, or do they reflect the difference between circumcisions (male or female) performed in American hospitals under sanitary conditions and using the most advanced surgical technology compared to those done under very unsanitary conditions using the most primitive tools? According to Gollaher, among the more common post-operative complications of male circumcision in the U.S. prior to the use of antibiotics included "inflammation, swelling, bleeding and hematoma". One surgeon, Jonathan Young Brown, remarked that almost invariably after a circumcision "the loose connective tissue lying between the remaining connective mucous and skin surfaces, become suddenly edematous, greatly swollen and occasionally almost tumefied. This condition delays or destroys union by the first intention, disfigures the part and renders the patient very uncomfortable." (quoted in Gollaher). If the complications associated with female circumcision in Africa can be shown, like early male circumcisions in the U.S., to be primarily a function of the circumstances under which they are performed, then shouldn't the effort be directed at improving the conditions under which female circumcisions are performed throughout Africa, as was done in the U.S.? Otherwise, shouldn't those attempting to eliminate female circumcision in Africa also be working to eliminate male circumcision in the U.S.? Wouldn't opposing only one form of circumcision be sexist? What other reason would opponents of female circumcision have for treating the two sexes differently in this matter?

|

|

|

Penises accidentally severed as a result of circumcisions in the U.S.

12. One also needs to think critically about the many claims that have been made regarding the medical complications associated with female circumcision. Authors have frequently stated that female circumcision produces trauma, infections and vaginal bleeding and often results in hospitalization and death. How accurate and serious are these claims? [Boyd (Circumcision Exposed), for example, makes comparable claims for male circumcision.] Do the various authors provide sufficient quantitative data to support their statements? For example, do specific complications occur 60-70% of the time or only 10-15% of the time? If authors don't give sufficient data, does the available independently collected data support their claims? How many girls, for example, have experienced the above symptoms? What percentage of those who have undergone circumcision have actually experienced serious health problems as a result of having been circumcised? The table below, which is based on a survey of 100 circumcised females in Sierra Leone, found that the overwhelming majority of girls experienced what was defined as "ordinary" problems, that is, normal side effects of vaginal surgery that do not differ from the side effects of male circumcisions practiced in the U.S. during the early 20th century. Similarly, while opponents of female circumcision routinely claim that the procedure either eliminates or severely reduces a woman's ability to have an orgasm, in a sample of 1,836 women in Nigeria, Coren (2003) reports that no significant difference was found in the ability of circumcised vs. uncircumcised women to experience an orgasm during sexual intercourse. Coren further states that "multivariable logistic regression models showed that cut women were significantly more likely than uncut women to report that they initiated sexual intercourse with their partner at least some of the time," seriously undercutting the credibility of recurring claims that circumcised women suffer a reduced enjoyment of sex.

However, some girls did suffer more serious consequences, and one even died. In one of the articles in the Circumcision packet (on reserve in the library), the author states that 5 girls died from having circumcision performed on them in Egypt. How meaningful are these figures? What is the context in which these deaths and serious complications took place? For example, how many boys suffered medical complications or died from circumcision within the same populations during the same time period? Oliver Gillie (see Doctor, Spare That Foreskin in the Circumcision packet) quotes a British surgeon who stated that he was personally aware of one death and three cases where part of the penis was severed, all within a few years. Boyd (Circumcision Exposed 1998:20) claims that at least 2-3 deaths per year are caused by circumcision in the U.S., with some estimates ranging considerably higher. Also, what was the total number of girls in Egypt who underwent circumcision during that time period in which the five deaths occurred, and can the deaths be directly attributed to the circumcision? Furthermore, are five deaths (however tragic) among perhaps hundreds of thousands --possibly millions-- of girls who underwent the operation significant in a developing country such as Egypt where medical care is very poor? According to one source, nearly 80 Egyptian women die in childbirth for every 100,000 children born. Similarly, infant mortality in African countries is exceedingly high. Infant mortality (ages 1-5) in Mozambique, for example, is 25 times that in the U.S. Is it, then, female circumcision that is the cause of these deaths, or is it the poor quality of the medical care that is available to the women who undergo the procedure? Might one solution to the problem --also, the solution that most respects cultural diversity-- be to medicalize female circumcision --that is, to have it performed in hospitals the way male circumcisions are performed in the U.S.? When, for example, abortion was legalized in the U.S. and performed in hospitals instead of in illegal clinics, the number of deaths that resulted from abortion dropped, according to one source, from an average of 293 women per year prior to 1973 to only 36 deaths in 1973.

|

13. Much has been written about the "primitive tools" used to perform female circumcisions in Africa. The fact is that the most common instruments used are traditional knives and razor blades. These are the same tools used to perform male circumcisions in these same societies? Razor blades and traditional knives are actually quite sharp and make reasonably clean cuts. Although broken bottles have received the most attention from opponents of female circumcision, they are, in fact, only rarely used (see Table below). In the interest of fairness, wouldn't it be reasonable to expect that those who oppose female circumcision because of the "crude tools" used oppose male circumcision for the same reasons? How might their application of a double standard reflect the interests of the individuals and groups leading the opposition rather than their concern for the welfare of the Africans undergoing circumcision? |

Female Circumcision Knife |

Maasai Male Circumcision Knives

|

Stone tools used in Australian subincision |

|

Too frequently, female circumcisions performed in rural villages in Africa are compared to male circumcisions in the U.S., which are almost exclusively performed in modern hospitals containing among the most sophisticated and sanitary surgical conditions available anywhere in the world. However, it is useful to be reminded that this was not always the case, that circumcisions in the U.S. and western Europe were at one time performed under conditions not unlike those which prevail in rural Africa today. This point is clearly illustrated by a Jewish circumcision performed in the late 19th century which is described in David Gollaher’s book, Circumcision: A History of the world’s Most Controversial Surgery, (2000, pp.25-26):

“For the better part of two thousand years, Jewish circumcision followed a three-step pattern. First was the chituch, the cutting of the stretched foreskin. Then came periah, the complete exposure of the glans of the penis effected by cutting or tearing away all of the inner foreskin tissue back to the frenulum. Finally, with the operation finished, came the mezizah, a practice in which the mohel sucked the blood from the wounded penis until the bleeding stopped. Ethnographer Felix Bryk (1934, Circumcision in Man and Woman, p.49) captured the classic technique of the mohel at work in the following passage.”

He takes the member by the thumb and forefinger of his left and rubs it several times gently to evoke an erection; he then takes hold of the outer and inner lamellae of the foreskin on both sides . . . and draws them down over the glans, pressing them smooth, by lifting his hand upward at the same time and thus giving the member a vertical position. The mohel now takes a pair of small pincers in the thumb and forefinger of his right hand and inserts the foreskin into the crack in such a manner that the glans comes to be behind it and the foreskin that is to be cut away in front of it. Then he takes hold of the knife with the first three fingers of his right hand in such a manner that it rests on the middle finger, with the index finger on the back of the knife and the thumb on the middle. With one vertical motion downwards he cuts off close to the plate part of the foreskin that is before it, which is being held with the left hand. If this has been done according to prescription . . . the foreskin itself is clipped at the tip, resulting in an opening about the size of a pea.

Gollaher indicates that at this point, the surgery was not yet finished. “To accomplish periah and complete the denudation of the glans, the mohel set aside his instruments and used only his thumbnail, long, lancet-shaped, filed to the sharpest edge.”

Directly after the cut has been made, the mohel puts the tip of his thumb nail . . . into the opening of the inner lamella of the foreskin, grasps the foreskin by its tip with the help of both index fingers, splits it on the back of the glans by means of slitting up to the crown of the latter, and shoves the slit foreskin up over the crown of the glans.

“The incisions completed, the mohel pinched the foreskin between his thumb and index finger and tore it away from the penis.”

“Mezizah b’peh followed immediately, the mohel taking the bleeding penis in his mouth, sucking the blood, then turning to take mouthfuls of wine from a goblet and spitting this wine on the infant’s wound.”

This is clearly not a description of the nice sanitary and painless circumcision that most people associate with male circumcision in the West.

14. Two articles included in the Circumcision packet placed on reserve in the library describe circumcision within a specific ethnographic context. Soitoti's article, "The Initiation of a Maasai Warrior," focuses on male circumcision among the Maasai, a cattle-herding society in Kenya in East Africa, while Sillah's article, "Bundu Trap," focuses on female circumcision among the Mandingo, an agricultural people in Sierra Leone in West Africa. How do the circumcision rituals of these two peoples function within the social life of their respective communities? How do the people themselves view their respective rituals? Why is it important to them? Might the circumcision rituals (superstructure) in both of these societies have an infrastructural and structural basis? If so, can we extrapolate this finding to other societies? How might it help us understand why circumcision rituals are performed in different societies?

15. Many feminists, such as Mary Daly (African Genital Mutilation: The Unspeakable Atrocities), see the practice of female circumcision in Africa and elsewhere as part of the subjugation of females in a "patriarchal" world. Is her interpretation of female circumcision correct? Does it accurately reflect the practice of female circumcision among African societies? Does it reflect the emic view of this practice? Does it provide a useful etic explanation of the practice? Does it, for example, account for the existence of both male and female circumcision among the Maasai? Does it effectively explain the practice of male circumcision in numerous so-called "patriarchal" societies that do not practice female circumcision, including the U.S.? Does it account for the practice of male subincision among the Australian aborigines? Can it account for the practice of male castration, such as occurred in Europe, or for the emasculation of males who become Hijras in India? In other words, do feminist explanations of female circumcision provide us with accurate, testable models that accurately explain the practice of male and female circumcision cross-culturally, or do they simply represent the imposition of Western beliefs and values on non-Western peoples? Might this be an example of what Frank Furedi calls the Cultural War of the North against the South? From an anthropological perspective, it is impossible to fully explain ritual genital surgeries without taking into consideration both the emic explanation of the procedures practiced and a cross-cultural etic statistical explanation of the occurrence and distribution of the various procedures. Furthermore, from a scientific perspective (Occam's Razor), an explanation that can account for the occurrence and distribution of both male and female genital surgery is superior to one that purports to explain just one type of genital surgery. It is important to keep in mind when considering Mary Daly's thesis that female circumcision represents the subjugation of women in male-dominated societies that the Jewish circumcision ritual described in #13 above was an honor bestowed only on males. Females were completely deprived of this privileged experience in traditional "Patriarchal" Jewish society, and still are today. (Significantly, no feminists have argued that Jewish females should be granted social equality by being allowed to experience this defining ritual of Jewish identity that has privileged Jewish males throughout history and that is believed to date to Yahweh's covenant with Abraham.)

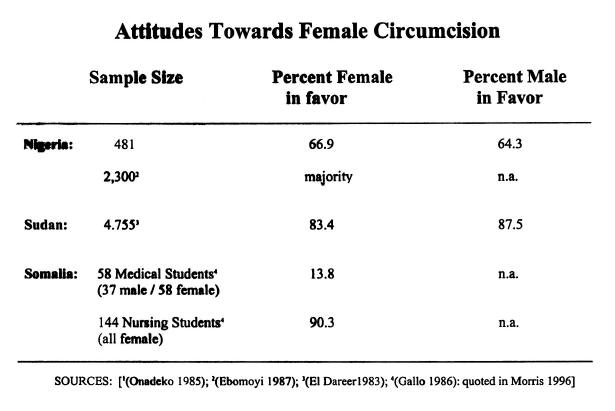

How do feminists such as Daly explain research that consistently shows that females are just as likely to support female circumcision as are males (see table below)? Rita Morris, for example, (The Culture of Female Circumcision in the Circumcision Packet) reports on several studies that show the high popularity of female circumcision among both men and women. In one sample of 453 Nigerian women, 71% of whom had been circumcised, 66.9% supported the practice, which was comparable to the 64.3% of the 28 men surveyed who supported it. Another survey of 1,150 Nigerian women similarly found that the majority of women supported female circumcision. Similarly, a survey of 3,210 females in the northern Sudan, where all three types of circumcision are performed --including infibulation-- found that over 80% of the females interviewed supported the continuation of female circumcision. A survey was also undertaken of 144 female nursing students and 95 medical students (37 males and 58 females) in Somalia, where infibulation is also practiced. Over 97% of the nursing students and 62% of the female medical students were themselves circumcised. The female nursing students overwhelmingly supported the continuation of female circumcision (90.3%), whereas only 13.8% of the medical students (male and female) advocated continuing the practice. These data simply do not support the notion that female circumcision is a practice imposed on women by a male dominated society. To assume that women are merely pawns in the perpetuation of a ritual of male dominance is not only not substantiated by the facts, it is demeaning to the women who practice and defend the ritual. It directly questions their intelligence and their character. Since most of these women are women of color, the attack on them by Westerners could be considered racist. The situation is far more complex than feminists such as Mary Daly would have us believe. Understanding the above statistics and the other facts associated with circumcision, infibulation, subincision and emasculation requires a conceptual approach to sex, gender and the study of gender relations that is far more complex and systemic than the simplistic explanations proposed by feminists such as Mary Daly. As with any belief that is not supported by the data, it is important to ask why individuals continue to believe what has been shown not to be true. How does the continuation of such beliefs serve the interests of the believer?

16. It is significant that it is primarily women who perform female circumcision throughout Africa and who are the ones fighting the hardest to preserve this tradition. Indeed, the all-female Bondo Society in Sierra Leone protested vehemently against the all-male government of Sierra Leone when that government passed a law banning female circumcision. A similar opposition occurred in Uganda. This raises a series of interesting questions. Does the fact that it is primarily women who both perform and defend female circumcision contradict feminist claims that female circumcision is about male dominance over women? Might it suggest that the practice of female circumcision requires a more complicated explanation than feminists such as Mary Daly offer? If some feminists claim that African women who promote and defend female circumcision are uneducated and don't know better, aren't they demeaning the intelligence and the character of these African women? Aren't they presenting an ad hominem critique? Could such statements even have racist implications? How have African women responded to this issue?

17. If feminist explanations cannot account for the facts associated with male/female circumcision, male subincision and male castration, we need to find an alternate explanation that does account for these facts --or at least one that accounts for the practice of genital surgery more effectively than do feminist theories. Might it be possible to account for this behavior from a Cultural Materialist perspective; that is, could there be an Infrastructural basis for the various forms of genital surgery, much as there is an Infrastructural basis for different forms of infanticide, residence patterns, kinship, family organization and other social behaviors? If we are able to develop a logically consistent and testable explanation for these different forms of genital surgery, what are the implications for competing feminist theories? Does the principle of Occam's Razor apply?

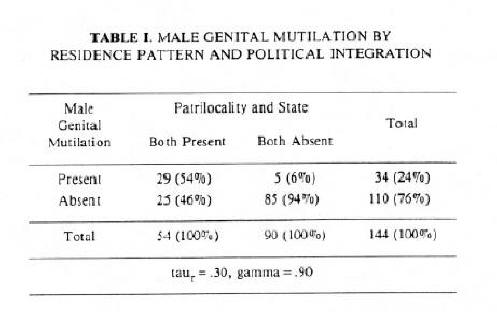

For example, the following three tables show that the incidence of male circumcision varies according to whether a particular society practices patrilocal post-marital residence and/or is organized at the state level (as opposed to being organized at the band, lineage, clan or tribal level). Male circumcision is more likely to occur in those societies in which patrilocal residence is practiced and is more likely NOT to occur in those societies in which patrilocal residence is not practiced. Similarly, male circumcision is more likely to occur in those societies that are organized at the state level and is more likely NOT to occur in those societies that are organized below the state level. There is also a strong relationship between patrilocal residence and state organization: pre-industrial state-level societies are generally both patrilocal and patrilineal. These societies also practice intensive agriculture, which is the infrastructural base upon which their patrilocal residence, patrilineal descent and state-level political organization (structure) are based.

|

|

|

Significantly, while male circumcision is practiced in many societies that do not also circumcise females, female circumcision is rarely practiced in societies that do not circumcise males. Indeed, Judith Brown (1963) found a very strong association between male and female circumcision in her cross-cultural study of female initiation rites.. According to Brown, "in societies practicing patrilocal residence in which men experience painful initiation rites in the form of genital operation or extensive tattooing, female initiation rites will also involve painful genital surgery or tattooing. (x2=19.19, p<.001)." In other words, female circumcision is not a degradation imposed on women. Rather, it is a by-product of male circumcision; those societies that honor women with circumcision are the same societies that honor the men through circumcision. However, the majority of societies that honor males through circumcision, including Jews, do not similarly honor females. ( Interestingly, Jewish feminists have not fought for equal treatment on this issue!)

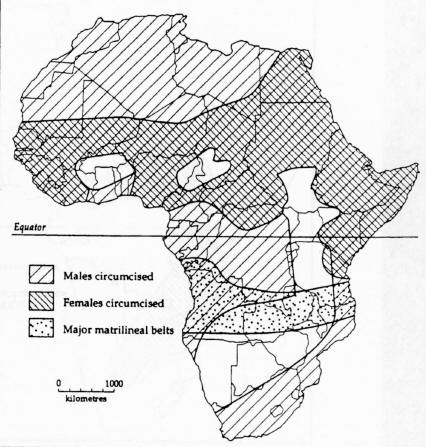

As the map below clearly illustrates, the practice of circumcision in Africa shows a distinct pattern. Male circumcision is practiced over a much larger portion of the continent than is female circumcision. Indeed, wherever female circumcision is practiced in Africa, male circumcision is also practiced. But the reverse is not true: large areas exist throughout Africa where male circumcision is practiced but where female circumcision is not practiced. Patrilineal descent is the predominant form of descent practiced among African societies, except for the territory specifically designated as the "matrilineal belt" on the map below. As would be expected, patrilineal descent generally occurs where patrilocal residence is practiced, and matrilineal descent occurs largely where matrilocal residence is practiced. Thus, both male and female circumcision are practiced among patrilocal-patrilineal societies in Africa, whereas only male circumcision is practiced among some of Africa's matrilocal-matrilineal societies. Since patrilocal-patrilineal societies are more likely to be "male oriented" than are matrilocal-matrilineal societies, both male and female circumcision occur more predominantly in male-oriented societies. Furthermore, male circumcision occurs much more commonly among Africa's male-oriented societies than does female circumcision. This flatly contradicts the feminist notion that female circumcision represents the subordination of women in male-dominated societies. If the feminist claim were true, we should find more female circumcision and less male circumcision practiced among "male-oriented" African societies. The feminist claim that female circumcision represents the subordination of women in male-dominated societies is simply not consistent with the data.

Rather than viewing African circumcision as a deprivation inflicted on individuals (especially women) by society in order to control their sexuality, it is more accurate from an anthropological perspective to see circumcision as a rite of passage through which individuals pass in order to earn the rights and privileges associated with adulthood in their respective societies. As the readings on both the Maasai and the Mandingo in the Circumcision packet illustrate, circumcision is a somewhat fearful ritual that each young boy or girl must endure in order to earn respect within the community and be treated as an adult. It is by viewing circumcision this way that we best understand its practice throughout Africa. I would argue that male circumcision originated before female circumcision and that female circumcision is largely a derived ritual that evolved in response to the privileges associated with male circumcision in male-oriented societies. It would make sense that a ritual which distinguishes "male identity" would evolve in those societies where males are more politically powerful and more highly valued. Rituals (Superstructure) are, after all, a function of the organized relationships (Structure) which exist in any given society and often serve to reinforce and legitimize the power differentials that exist within a society. Just as circumcision served to enhance Jewish separateness and superiority in relation to non-Jews, so also does male circumcision serve to draw attention to male distinction and superiority in male-oriented African societies. Female circumcision may be seen as a social adaptation whereby females in male-oriented societies evolved a comparable ritual of gender identity. In the jargon of contemporary feminism, female circumcision likely represents female empowerment rather than female subordination. This explains: (1) why female circumcision is mostly practiced in those societies that already practice male circumcision; (2) why female circumcision is performed exclusively by women in "women-only" associations; (3) why men are specifically excluded from participation in female circumcision rituals; and (4) why many African women have been so tenacious in defending the practice of female circumcision from attack by outsiders.

|

18. Is it sexist and/or logically inconsistent for Americans to criticize Africans for practicing female circumcision, but not for practicing male circumcision? Could this be a reflection of our ethnocentrism? Do we in the U.S. condone male circumcision simply because we practice it ourselves and, therefore, accept it as legitimate? The most common reason given by parents for having their daughters circumcised in Africa is tradition. Does the average American have their son circumcised for medical reasons, or is it also performed simply because that is what is normally done in the U.S. (i.e., "tradition")? Do the various claims presented today for the medical benefits of circumcision stand up to scientific scrutiny any better than the claims made a century ago? (see, for example, Immunological Functions of the Human Prepuce) What official position has the American Pediatric Association taken with regard to male circumcision? If there are no compelling medical reason for practicing male circumcision and there are known negative consequences, is it consistent to be concerned about female circumcision but not about male circumcision? The U.S. Government has passed a law prohibiting female circumcision. Why doesn't the U.S. pass a law banning male circumcision? Are there legitimate medical reasons for this legal double standard, or do vested interests exist in our society that would oppose the banning of male circumcision? Could it be that Congress is willing to tolerate genital surgery when it is practiced by one social or religious group, but not by another? |

Turkish Boy Being Circumcised |

19. Many black women, including African women, have spoken out against female circumcision. However, they are largely members of the urban, educated elite. Might the conflict over female circumcision in Africa, then, be a class or ethnic conflict rather than a gender conflict? Could it represent a conflict between urban African women who value the new Western lifestyle and participation in the emerging urban-based global economy and those who live in rural regions (male and female) who still adhere to traditional lifestyles? What role might opponents of female circumcision play in advancing Western neocolonialism through their attempts to eradicate female circumcision? To what extent do they advance the interests of the urban elite (who are economically and politically allied with the West) over the interests of the poorer rural populations who might be resisting increasing urban domination of their lives? Could opposition to female circumcision in Africa be an aspect of globalization? Could it be a factor contributing to anti-American and anti-Western sentiment in Africa and the Middle East.

20. If the conflict over female circumcision represents a class conflict, to what extent might the massive attempt to eradicate female circumcision actually have the opposite effect intended? When people's traditions are being attacked, they are likely to go to great lengths to preserve those traditions. They become important symbols of their social and ethnic identification. Three thousand years of Jewish history is a testament to this fact. When the Roman Empire attempted to outlaw male circumcision among the Jews in 132CE, a major revolt erupted against the Roman Empire in Palestine. To what extent might the opponents of female circumcision be achieving the opposite of their goal of eradicating this procedure? To what extent might they instead be making the situation worse for the young girls undergoing circumcision? Could the opponents of female circumcision be forcing people to perform female circumcision in secret, under less sanitary conditions, and not bringing their daughters to the hospital when problems occur for fear of being prosecuted? Might it be better to accommodate those who want to practice female circumcision so that the ritual can be performed safely in hospitals rather than under primitive conditions? Wasn't this one of the justifications used for legalizing abortion in the U.S.?

The Circumcision of Jesus |

Modern African Circumcision |

21. Those who oppose female circumcision emphasize the radical surgical procedure that is performed with the female vagina being sewn closed. The more radical procedure (infibulation) is almost exclusively restricted to three countries: Egypt, Sudan and Somalia. Of the four types of female circumcision described, the less radical forms (types I & II) are by far the most common. In one survey in northern Ghana, only 39% of 195 women interviewed were circumcised, and all by the least radical methods (types I & II). Why might opponents of female circumcision emphasize the most radical form of the procedure, even though these are not the most common? How might it serve their interests to do so? What does it say about the integrity and credibility of their argument?

22. Billions of dollars are spent in the United States every year to pay for breast implants, liposuction, collagen lip injections, tattoos, body piercing, etc. Most of these procedures are performed for cosmetic rather than medical reasons, and all of them cause pain and suffering. In addition, many result in medical complications and cause long term health problems. Is it reasonable and logically consistent for Americans to undergo these procedures on such an immense scale while criticizing Africans and others of being "barbaric" for practicing female circumcision?

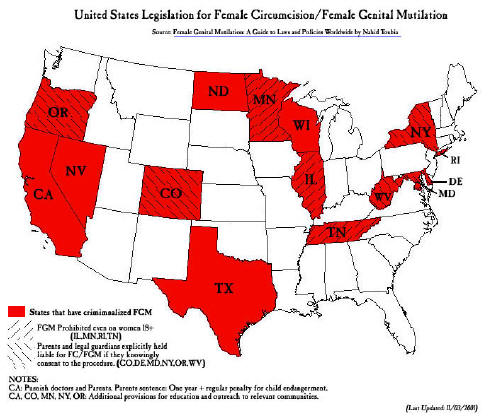

Several states in the U.S. have passed laws outlawing female circumcision, but no state has passed a law outlawing male circumcision. Similarly, when Pat Schroeder (D-Colorado) introduced a bill in Congress (HR3247) to outlaw female circumcision in the U.S., she refused to extend that bill to include male circumcision.

23. Several years ago, doctors at Harborview Hospital in Seattle attempted to accommodate women from other countries, particularly Somalia, by performing a minimal female circumcision at the time of their daughters' births. The procedure would have involved less damage to the female's genitalia than is routinely done to males in the U.S. during male circumcision. It is significant that the issue arose when one doctor at the hospital asked a Somali patient whether or not she wanted her baby circumcised if it was a boy. He thought nothing of circumcising boys, but was taken aback by the mother's response that she wanted the baby circumcised if it was a girl as well. In any case, the doctors (male and female) encountered determined opposition from women's groups when they proposed the milder surgical procedure, despite the fact that they proposed the procedure in order to accommodate the Somali women and to keep them from taking their daughters back to Somalia to have the far more drastic infibulation procedure performed. Is it equitable or is it sexist to oppose a female circumcision that would be less drastic than is normally done to males, yet at the same time condone and practice male circumcision? Does it make sense for women's groups to oppose the milder circumcision proposed by the doctors when the likely result of not performing is that the Somali mothers will send their daughters back to Somalia to have the more drastic infibulation procedure done? Might the women's group's opposition in this case be seen as a slippery slope argument similar to that used by the NRA, by both pro-choice and pro-life advocates and by other groups who see their interests threatened by accommodations made to those with whom they disagree?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Here are two newspaper articles on circumcision accidents:

one in the U.S. and one in Canada:

BABY BLEEDS TO DEATH AFTER CIRCUMCISIONMiami Herald June 26, 1993

The Miami Herald reported the death of 6 month old Carol City baby, Demetrius Manker. Manker bled to death after being circumcised. "I can't express the way it has affected me emotionally," the child's mother, Louise Manker, said. "It's something I'll never get over. This was my last child." A Miami pediatrician circumcised 25-pound Demetrius Manker in his office. After his mother took him home, she saw he was bleeding from the incision. Manker subsequently called the doctor several times, according to their attorney, Patrick Cordero. "One of the instructions was that she put Vaseline around the penis area to stop the bleeding." Cordero said, "she followed the instructions to the letter." Louise Manker's sister grew so alarmed by his continued bleeding that she called paramedics, Cordero said. He was pronounced dead at the hospital. An autopsy showed that his liver and other organs had gone pale from the loss of blood, said Dade [County] Chief Medical Examiner Dr. Charles Wetli. "The message to get across is that this is weird, unusual," Wetli said. "I've done close to six thousand autopsies and this is the first I've seen where a baby died from circumcision. It's probably the safest procedure you could think of. An autopsy revealed a seemly normal circumcision, Wetli said. The doctor who performed the surgery, Robert D. Young, said the circumcision had gone well. "I would not have let him go home if I didn't think so. Medical examiners will confirm the soundness of the operation. Authorities say they will try to determine if the baby suffered from some rare disease that prevented his blood from coagulating. It's also possible that Louise Manker did not understand the extent of the bleeding, especially because a baby has a fraction of an adult's blood supply, Wetli said. "There's two parts to the story," the deputy medical examiner said, Why was the child bleeding? And secondly what was the level of communication if the mother said he's bleeding but didn't say how much.

|

~~~~~~~~~~

`Totally Unexpected' Death of Baby ProbedFive-week-old infant died after hewas circumcised at Penticton hospital

Jason Proctor The Province Thursday, August 29, 2002

The Kamloops coroner is investigating the case of an infant who died last week from complications following his circumcision at Penticton Regional Hospital. The five-week-old child was released after the procedure last Tuesday morning, but his parents went back to talk to the doctor later that day with concerns about bleeding. They returned home, but the situation worsened overnight, forcing them to rush the child back to hospital early Wednesday. The infant was flown by air ambulance to Vancouver, where he died last Thursday in B.C. Children's Hospital. "It certainly seems to be unusual," coroner Ian McKichan said yesterday. "It's definitely something that warrants an investigation, because it's a totally unexpected sort of death." Deaths following circumcision are almost unheard of, but like any operation, bleeding and infection are the greatest dangers. The case raises questions about an increasingly rare operation which stirs controversy in some circles. "The bottom line is that circumcision is becoming a less-common procedure," said Dr. Morris Van Andel, registrar of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of B.C. "It's no longer an insured service -- it's considered an option. That makes it all the more distressing when you hear about something like this." According to Penticton hospital officials, the operation to remove the foreskin from the child's penis was conducted by a physician with 16 years' practice in British Columbia. The coroner's office is now awaiting the results of an autopsy being performed in Vancouver. McKichan said the investigation could take up to three months. The college will likely also investigate the case after the coroner's inquiry is finished, to determine whether the death is the result of medical complications or malpractice. Decades ago, nearly all Canadian boys were circumcised shortly after birth, but the Canadian Paediatric Society no longer recommends the procedure. It is now done mainly on religious grounds -- primarily by Jews and Muslims. Because of the drop in popularity and increasing medical cost-cutting, children are usually circumcised at a doctor's office or as hospital out-patients. Doctors generally observe a child for about an hour, and then instruct parents to watch for trouble. "Instead of being observed by professional staff, the parents are left on their own," said Dr. Shelley Ross, a Burnaby family doctor. "If a person wants to get it done, should they be pushed into not having professional observation because of the cost?" Doctors say the best time to perform a circumcision is in the first few weeks after birth. The operation should take 10 to 15 minutes under a local anesthetic, performed with a clamp designed to seal the blood-vessels. "The amount of blood you should see with this type of procedure, should be no more than a [bit] on the diaper," said Ross. "You need experienced hands. You need to to know what you're doing."

|

~~~~~~~~~~

Incidence of Circumcision in British Columbia, Canada

The male neonatal circumcision rate in British Columbia peaked in the 1970s, when it reached nearly 60%. The rate has declined steadily since then. Routine neonatal circumcision was removed from the insured services list on April 1, 1984. As of that date, it was no longer covered by the government health plan. In recent years, the number of circumcisions performed in hospitals1 has been as follows:

Source: British Columbia Ministry of Health.

|

|

R. L. Baker . "Newborn Male Circumcision: Needless and Dangerous." Sexual Medicine Today 1979;3(11):35-36

N. Williams and L. Kapila, "Complications of Circumcision." British Journal of Surgery 80, 1231-1236, (October 1993).

David Gollaher, "From Ritual to Science: The Medical Transformation of Circumcision in America." Journal of Social History, vol. 28, (Fall 1994).

S. Deegan, "What Gives International Agencies the Authority to Demand a Ban on Female Circumcision?" Living Marxism Issue 72, (October 1994).

P

M Fleiss, F M Hodges, R S Van Howe,

R. S. Van Howe, "Circumcision and HIV infection: Review of the Literature and Meta-analysis." International Journal of STD & AIDS 10:8-16 (1999).

Gregory J. Boyle and Gillian A. Bensley, "Adverse Sexual and Psychological Effects of Male Infant Circumcision." Psychological Reports (Missoula) 88: 1105-1106 (2001).

C. Coren, "Genital Cutting May Alter, Rather Than Eliminate Women's Sexual Sensations." International Family Planning Perspectives 29 (1). March 2003.

American Academy of Pediatrics,

Circumcise This!

|

Male Genital Mutilation (and then some!)

Azande

Male

Mutilated

for Adultery

"The adulterer's penis and scrotum were cut off and his hands chopped off. The truncated arms were then dipped in boiling oil to prevent his bleeding to death. But in spite of this, his legitimate wife continues to care for him lovingly, and he satisfies her now with the stump of his arm." (Felix Bryk, Circumcision in Man and Woman: Its History, Psychology and Ethnology. NY: American Ethnological Press, 1934:125.)

The Holy Foreskin Foreskins For Sale

"With one foreskin, you can grow about six football fields worth of skin through current cell culture techniques." --see D. Gollaher (2000:123) |

Selected Readings

Babatunde, Emmanuel. 1998. Women's Rights vs. Women's Rites: A Study of Circumcision among the Ketu Yoruba of South Western Nigeria. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

Boyd, Billy Ray. 1998. Circumcision Exposed: Rethinking a Medical and Cultural Tradition. The Crossing Press, Freedom, CA

Bryk, Felix. 1934. Circumcision in Man and Woman: Its History, Psychology and Ethnology. American Ethnological Press. NY

Gollaher, David. 2000. Circumcision: A History of the World's Most Controversial Surgery. NY, Basic Books.

Gruenbaum, Ellen. 2001. The Female Circumcision Controversy: An Anthropological Perspective. U. of Penn Press.

Herdt, Gilbert. 2006. The Sanambia: Ritual, Sexuality, and Change in Papua New Guinea., second ed. Wadsworth.

Ottenberg, Simon. 1989. Boyhood Rituals in an African Society: An Interpretation. Univ. of Washington Press.

Remondino, P.C. 1900. History of Circumcision from the Earliest Times to the Present: Moral and Physical Reasons for Its Prominence. Phila. F.A. Davis Company.

Richards, Audrey. 1956. Chisungu: A Girl’s Initiation Ceremony among the Bemba of Zambia. London, Routledge,

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

|

|

|