SOCIOPOLITICAL

IMPLICATIONS OF THE PERSISTENT

CONCERN

WITH GLOBAL POPULATION GROWTH

William S. Abruzzi

FORUM: of the Association for Arid Lands Studies. (2002)

ABSTRACT:

This paper argues that mainstream concerns

about overpopulation and the programs designed to limit population growth

in developing countries are ill founded.

The paper also argues that the international population control

policies developed by Western countries serve primarily their own

competitive interests, not the interests of the countries they are

designed to help. The paper

concludes that neo-Malthusian population theories predominate in the

international arena because they perform the same sociopolitical function

for the globally dominant societies today that earlier Malthusian theories

performed for upper classes within Western societies: a rationalization

and justification to controlling the reproduction of the poor.

KEY WORDS: overpopulation, neo-Malthusianism, competitive fertility, neocolonialism

* * * * *

October 12, 1999 was officially designated “Y6B-Day” in recognition of the fact that based on projections of population growth, the human population reached the six billion mark that day. However, Y6B was not coined to celebrate the existence of six billion people as a human achievement, but rather to mark that date as a harbinger of human disaster. Indeed, for the past half-century, academics, politicians, environmentalists and international development specialists have expressed increasing concern over the burgeoning growth of the human population. For nearly 50 years, the popular media has presented the American public with a rather frightening view of global population growth. According to Wilmoth and Ball (1992), articles advancing a "threatening" view of human population growth have consistently dominated the media, accounting for the clear majority of all articles published. Paul Ehrlich, a leading advocate of population control, was, according to Wilmoth and Hall (1992:637), the most prolific author on the subject of population growth during the last 50 years, with 24 articles published. He was also among the most frequently cited authors in the other articles written (ibid.).

Ehrlich (1968) predicted in The Population Bomb that human population growth would very quickly lead to mass starvation throughout the world. According to Ehrlich (1968:xi), "the battle to feed all of humanity is over . . . hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death." The earth, he claimed, simply could not support the six billion people projected to exist by the year 2000. In a subsequent article titled "Eco-Catastrophe," Ehrlich (1969:28) claimed, "by 1985 enough millions will have died to reduce the earth's population to some acceptable level, like 1.5 billion people."

Innumerable other writers have also issued dire warnings regarding the consequences of global population growth. Most of this concern has focused on population growth in the Third World. Initially, attention was directed at the negative economic consequences of rapid population growth. While the population control community’s focus is primarily on Africa today, during the 1950s and 1960s most of its attention was directed towards Asia, which displayed the greatest population growth at that time. William Vogt (a sociologist, quoted in Hartmann 1987:145) claimed in 1960,

China quite literally cannot feed more people … The greatest tragedy that China could suffer, at the present time, would be a reduction in her death rate. … Millions are going to die. … There can be no way out. These men and women, boys and girls, must starve as tragic sacrifices on the twin alters of uncontrolled reproduction and uncontrolled abuse of the land.

Today, China, with a population double that of the 1960s, maintains one of the highest economic growth rates in the world, and the social and environmental problems that it faces are those associated with its rapidly increasing wealth and development, not with the poverty and underdevelopment it was predicted to encounter.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s attention shifted away from a concern with the negative impact of population growth on economic development to a variety of concerns regarding the impact of human population growth on the natural environment. Three feared consequences of population growth received the most attention initially: (1) the depletion of limited resources, (2) a decrease in the quality of the environment, and (3) a decline in global biodiversity due to an increase in the number of species extinctions. The specter of global warming has more recently been added to the list.

The first of these concerns was most notably expressed by the "Club of Rome", which published The Limits to Growth in 1972 (see Meadows, et al. 1972). Using computer models, the Club of Rome established specific dates at which the world would run out of critical resources. According to The Limits to Growth, the resources listed below would be exhausted in the following order:

|

|

|

As predictions of resource depletion failed to materialize, the population control community shifted its attention away from a focus on resource depletion towards a more encompassing concern with global environmental deterioration. Harrison (1993:42), for example, conceded that, “human ingenuity has so far been able to increase world food production in line with the increase in human numbers.” However, he alternately presented the impending global crisis in even more ominous terms. Harrison (1993:53-54) proposed that what lay in store was “not a resource crisis but a pollution crisis. … Life may survive in some lowly form, but we may not.”.

Human population growth has also been presented as a major threat to the survival of thousands --even millions-- of other species. Norman Myers in The Sinking Ark (1979) claimed (without presenting any data) that 40,000 species were becoming extinct each year, a figure that was later repeated by Al Gore in his book, Earth in the Balance (1992). In 1981, Paul Ehrlich maintained that 250,000 species were being lost each year and predicted that half the species on earth would be extinct by the year 2000, with the remaining species lost by 2025 (Stork 1997:62). In response to criticisms of such high estimates, E.O. Wilson claimed that the figure was easily 100,000 per year (Mann 1991:737). In a recent survey conducted by the American Museum of Natural History, 70% of biologists believed that a mass extinction was already underway and that up to 20% of all living species could disappear within the next 30 years due to human activity (Warrick 1998). The above claims have been largely based on models of species decline that contain dubious and unsubstantiated assumptions regarding the number of existing species and the rate of species decline (see Lomborg 2001: 249-257). These above predictions have also, for the most part, not been based on quantitative data and have ignored empirical research which suggests that such dire predictions may be seriously overstated (c.f., Lugo, 1988; Simberloff, 1992).

Population growth has even been offered as the ultimate source of most social problems facing society: from violence and political instability (see Homer-Dixon et al. 1993) to crime and urban sprawl (see Nowak 1998). Mark Nowak, former Executive Director of Population-Environment Balance and currently a research associate at No Population Growth (NPG) contends, “as population growth in our cities has increased, so have crime and competition for housing. As a result, Americans have taken to the suburbs to find cheaper housing and to regain open space and solitude.” Such sweeping claims ignore the fact that suburban migration preceded rising crime rates in the cities. They are also contradicted by the fact that the most rapid population growth has been in the suburbs, which exhibit much lower crime rates than the cities, and that most urban areas have been experiencing actual population decline. The causes of crime in the city are far more complicated than such simplistic demographic arguments suggest and have more to do with the movement of businesses away from urban centers and the consequent decline of urban economies.

The whole literature on population growth has the feel of an impending doom in which the quality of human existence and the state of the global environment have not only been rapidly deteriorating, but are destined to get worse. Moreover, the tone of the much of the overpopulation literature reflects an air of conviction, at times tinged with hysteria. The degree to which the certainty of overpopulation and its consequent problems is completely accepted by those advocating drastic population control is perhaps best expressed by John Weeks, a sociological demographer, whose book Population: An Introduction to Concepts and Issues is one of the most widely used college textbooks on population in the world. In the Introduction to his book, Weeks, (1999:1-7), rather cavalierly attributes one global problem after another to the “relentless increase in population,” including the suburbanization of Walden Pond, labor migration from Mexico, high Palestinian unemployment and armed conflict between Hutu and Tutsi in Rwanda. Later in the book, after projecting an unrealistic future global population of nearly 30 billion by the end of the 21st century, Weeks (1999:458) poses the following (presumably self-evident) question to the reader: “You tell me. Is the world in 2000 more crowded, more polluted, less stable economically and more vulnerable to disruption than the world in 1980? The answer has to be yes” (emphasis mine).

POPULATION GROWTH AND

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Given the certainty with which population control advocates have presented their arguments, it is reasonable to ask whether clear empirical support exists for the impending doom they claim will occur. Unfortunately, insufficient space exists here to discuss all of the claims presented, or even to discuss any single claim in much detail. This paper will, therefore, touch briefly on just two of the general assertions that have been made: (1) that population growth has been a primary factor causing poverty and underdevelopment in the Third World; and (2) that population growth is a major cause of environmental deterioration.

No convincing evidence exists which demonstrates that population growth serves as an obstacle to economic development. The National Research Council (1986:4) concluded that “no statistical association …(exists)… between national rates of population growth and growth rates of income per capita.” Indeed, as Frank Furedi (1997:35) observes, “the specialist literature exhibits a profound tension between the intuition that population growth has negative consequences for the living standards of developing societies, and the absence of empirical evidence to substantiate this sentiment. … When it comes to deciding on the impact of population growth, ‘feelings’ still tend to account for more than facts.”

The dominance of feelings over data is clearly evident in the following statement by Paul Ehrlich (1968:15):

I have understood the population explosion intellectually for a long time. I came to understand it emotionally one stinking hot night in Delhi, a few years ago. … The streets seemed alive with people. People eating, people washing, people sleeping. People visiting, arguing and screaming. People thrusting their hands through the taxi window, begging. People defecating and urinating. People clinging to buses. People herding animals. People, people, people, people. … since that night I’ve known the feel of overpopulation.

Ehrlich's “emotional” understanding of "The Population Bomb" was, in fact, based on a serious misunderstanding of the situation. In his reaction to the situation in Delhi, Ehrlich was clearly confusing high population density with poverty and assuming that the presence of the former caused the existence of the latter. However, the available data simply do not support the notion that population growth and increasing population density have caused a decline in global living standards, or that they are a primary cause of poverty, underdevelopment and human suffering. New York, London and Tokyo are all substantially larger and more densely settled cities than Delhi, but do not display the kind of poverty described by above Ehrlich.

The crude birth rate in the U.S. throughout the 17th and 18th centuries was 55 births per 1000 population, comparable to the highest national birth rates recorded in the world today (Weeks, 1999:27). As a result of its high birth rate, the U.S. population doubled every 25 years, a development which Malthus claimed was unsustainable (see Malthus, 1826: Chapter 2). However, the U.S. population continued its rapid increase: from 5 million in 1800 to 75 million in 1900 and then to nearly 280 million in 2000. The U.S. population, thus, increased 1,400% during the 19th century and 273% during the 20th century. Today, the U.S. still maintains among the highest population growth rates in the world, comparable to those of China, Zimbabwe and Thailand. Clearly, rapid population growth did not obstruct economic development in the U.S. during the past several centuries, and its continued increase has not undermined the growth of the American economy today. Population growth cannot, therefore, be used to explain the lack of economic development elsewhere.

Japan presents a similar contradiction to the argument that population growth undermines economic development. Japan's population was only 40 million in 1900, whereas it is approaching 130 million today. The Japanese population has, thus, increased more than 200% in the past 100 years. Furthermore, 128 million Japanese --a population 46% the size of the U.S. population-- lives in a country smaller than the state of California. Average population density (a rough approximation for the relationship between population and available resources) in Japan is 330 people per km2, compared to 79 people per km2 in California and only 29 people per km2 in the U.S. as a whole. Moreover, because Japan is an island nation and is, therefore, largely mountainous, the bulk of the Japanese population is actually concentrated on less than 50% of the country's total land surface. Consequently, in Japan a population nearly half the size of the entire U.S. population effectively inhabits a land surface the size of southern California. Japan is also acknowledged to be one of the poorest countries in the world regarding the availability of natural resources. Yet, Japan maintains both the highest per capita GDP in the world and the world’s longest average life expectancy. Japan’s Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE) is 73.8 years compared to 67.2 years in the U.S. or 35.4 years in Ethiopia, 35.6 years in Uganda and only 29.5 years in Sierra Leone, the country with the world’s shortest life expectancy (WHO 2001: Table 4 Annex). According to both Malthusian and neo-Malthusian population theory, it is the Japanese, not Africans, who should be suffering and living in abject poverty.

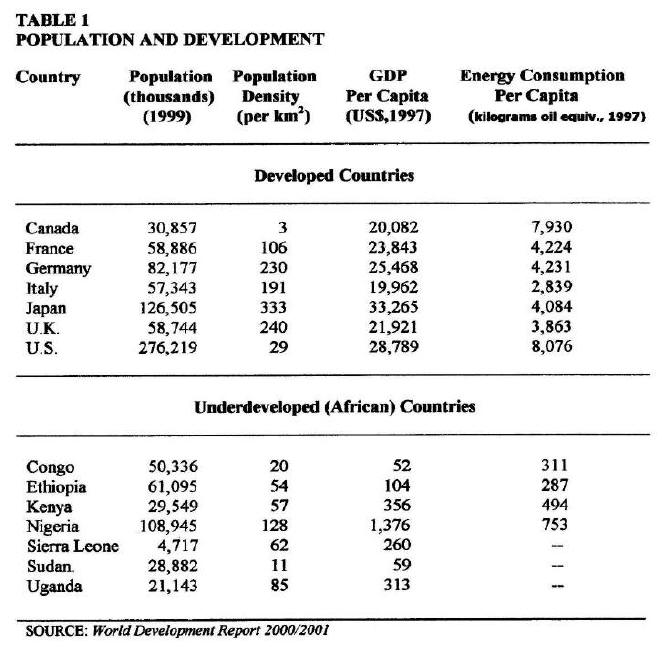

Indeed, if we compare the countries of Africa (the poorest countries in the world) with the U.S., Japan and the other G7 Countries (the wealthiest countries in the world), the Malthusian argument disintegrates even more profoundly. As Table 1 clearly shows, the wealthiest countries of the world have among the largest and most densely settled populations and consume the greatest amount of energy. By contrast, the African countries listed contain among the smallest and least densely settled populations in the world and command only a fraction of the energy consumed by those living in the developed countries. Population density in Europe is about twice that of Nigeria, the most densely settled country in Africa, nearly 5 times that of either Ethiopia or Kenya and 30 times that of the Congo. In addition, per capita energy consumption in Canada and the U.S. is about twice that of their European counterparts, 16 times that of Kenya and 28 times that of Ethiopia. The energy consumed in the U.S. alone is sufficient to maintain 4.5 billion Kenyans, over 7 billion Congolese or nearly 8 billion Ethiopians. The African countries are also larger in area and contain more abundant natural resources than most of the developed countries, especially Japan and the countries of Europe. One could easily argue that the goals of sustainability and resource conservation would be better served if North Americans rather than Africans were the primary target of international population control programs.

Population growth cannot be linked to famine or malnutrition either. The price of food on the global market has declined substantially over the past 40 years to where foodstuffs today cost, on average, less than one-third of what they cost during the 1950s (see Lomborg 2002:62). If there were insufficient food to feed the world’s population, the price of food should have increased, not decreased; it certainly should not have decreased by over two-thirds. According to the best available statistics, nutritional standards throughout the world (in developed and underdeveloped countries alike) have steadily improved during the past 40 years (see Lomborg 2002:109), at the very time that global population more than doubled. By every single health statistic, the human species is on average better fed and freer from disease than at any time in its history. While local famines have occurred, they are much less frequent than in the past and have not been caused by overpopulation. They have also resulted from specific local sociopolitical conditions, rather than from environmental deterioration or the inability of people to grow enough food, as has been made evident in such diverse countries as Liberia, Sierra Leone, Ethiopia, Malawi and North Korea.

POPULATION GROWTH AND

ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION

Attempts to link population growth with environmental deterioration have also proven largely unsuccessful. Claims, for example, that population growth demands increased agricultural production, which in turn leads inevitably to soil deterioration, are simply not accurate. The intensity of agricultural production is far greater in the U.S., Europe and Japan than it is anywhere in Africa. Yet, the latter countries display far worse soil erosion than do the former. That soil erosion in Africa is primarily a product of poor soil management practices rather than either population growth or inherent soil vulnerability has been shown by Tiffen, Mortimore and Gichuki’s (1994) investigation of population growth and agricultural development in the semi-arid Machakos District, Kenya. In 1937, a British soil conservation officer described the Machakos region in rather bleak terms:

… an appalling example of a large area of land which has been subjected to uncoordinated and practically uncontrolled development by natives whose multiplication and the increase of whose stock has been permitted, free from the checks of war and largely from those of disease, under benevolent British Rule. … Every phase of misuse of land is vividly and poignantly displayed in this reserve, the inhabitants of which are rapidly drifting to a state of hopeless and miserable poverty and their land to a parching desert of rocks, stones and sand (quoted in Mortimore and Tiffen 1994:10-11).

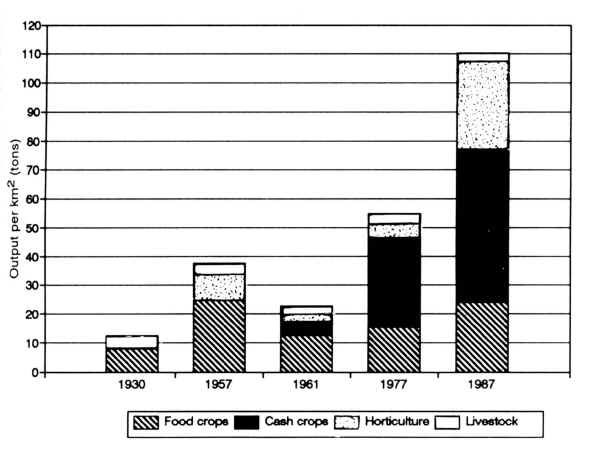

During the 1950s, however, more than 40,000 hectares of land in the Machakos District were terraced. Terracing was resumed following a brief hiatus accompanying the movement to independence in 1962, and by 1985 the majority of arable land in the district was adequately conserved. Today, 100% of the arable land in the district is protected. Local farmers also adopted moldboard plows, replaced long fallows with manuring and shifted from pasture-grazing to stall-feeding their livestock in their efforts to both increase agricultural productivity and enhance soil conservation. As a result, agricultural production quadrupled between the 1930s and 1980s, and tree-density on farmlands increased to 34 trees per hectare, at the same time that the Machakos District population grew from 240,000 to nearly 1,4000,000. According to Mortimore, Tiffen and Gichuki (1994), the recovery and development of agricultural land in Machakos was an endogenous process that occurred largely after independence. That process, according to them, resulted from increasing population density, the growth in local and regional markets and the existence of supportive economic conditions, in a manner consistent with the non-Malthusian model of economic development presented by Ester Boserup (Boserup, 1965).

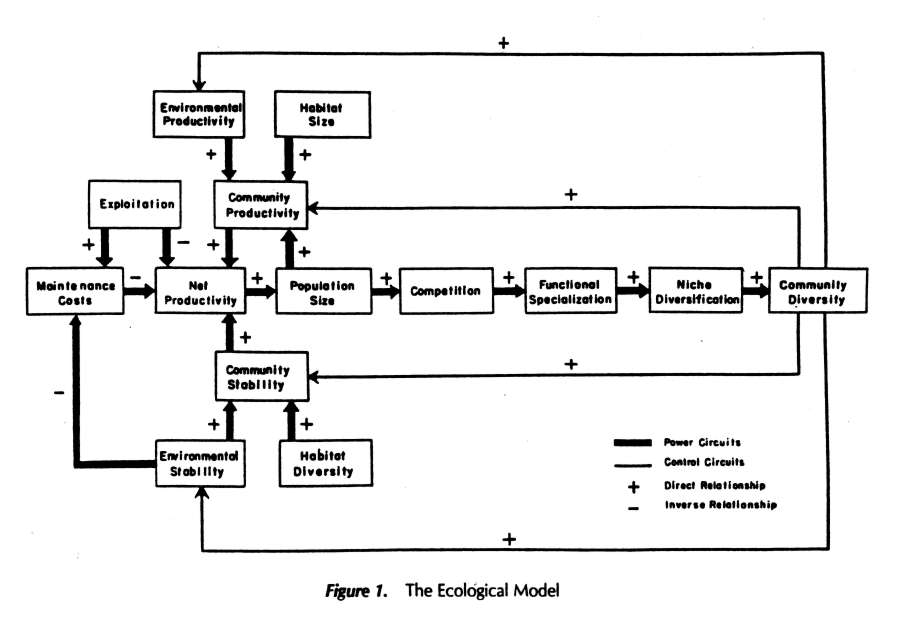

Figure 1

Agricultural Productivity in Machakos

1930 - 1987

High rural population densities have been maintained without serious environmental degradation elsewhere in Africa as well, most notably in the Kano close-settled zone in semi-arid northern Nigeria where rural densities of 500 people per km2 have been maintained for several centuries (see Mortimore 1993; Harrison 1993). Population growth does not, therefore, inherently increase soil erosion. In fact, high rural population densities are frequently advantageous for resource conservation. Not only does increased rural density increase the market value of land (and, therefore, the economic incentive to maintain and protect the land), but denser populations are also better able to provide the labor required to perform the many tasks needed to conserve the land, including soil preparation, mulching, weeding, terrace preservation and the maintenance of irrigation systems. Decreases in rural density have on several occasions been associated with increased soil erosion, due to the inability of reduced populations to continue to perform essential resource conservation tasks (see Turner, Hyden and Kates 1993; Furedi 1997: 39, 156).

MALTHUSIAN

NEOCOLONIALISM

It is significant that during the very time period in which funding for family planning research and programs increased dramatically, the rate and absolute size of global population growth steadily declined. The rate of global population growth peaked (at nearly 2 percent) in the early 1960s, and absolute annual population increase peaked (at nearly 90 million) in 1990 (see Lomborg 2002:47).

Today, the majority of countries in the world maintain below-replacement fertility levels. Many countries, including Japan and most European countries, face the real prospect of absolute population decline. However, despite the fact that the rate of global population growth has been steadily declining for nearly four decades and that predictions of future world population size have had to be repeatedly revised downward, both the concern with overpopulation and the funding for family planning has continued unabated. While many population control advocates have claimed that this decline has resulted from the work of population control programs, the reality is that such declines have frequently occurred in the absence of population control programs (including historically in the U.S., Europe and Japan) and can more accurately be attributed to changes in the underlying socioeconomic conditions that favor reduced fertility.

Given the fact that population growth has been slowing for several decades, it is reasonable to ask why the concern for and funding of population control programs has continued to increase. Furthermore, given the fact that the U.S. population has been increasing at a rapid rate, nearly 100% since 1950, it is also reasonable to ask why the population lobby has not expressed nearly as much desire to control population growth in the U.S. (the most environmentally expensive population on earth) as it has in controlling population growth elsewhere in the world. In other words, why are population control programs primarily directed at people and populations in Africa, Asia, and Latin America? To understand this, we need to consider the political economy underlying population policies.

Population policies illustrate what Furedi (1997:12-25) calls “competitive fertility,” wherein the demographic concerns of one social group, or political entity, reflect that group’s economic, political and military relations with other potentially competing populations. The underlying demographic concern is with the competitive implications of differences in reproduction and population growth. Thus, just as many whites in the U.S. worry about immigration and about Black or Hispanic reproduction because of the implications this has for continued white control of the American political economy, nationals in EU countries have been concerned about the growing size of immigrant populations within their borders. For the same reason, census data becomes a volatile political issue in multiethnic countries such as Nigeria, where the Yoruba and Ibo fear the growing Hausa population in the North (see Kokole 1994). Edward Ross (1907:616) expressed the prevalence of this concern nearly a century ago.

Numbers tell. France dreads prolific Germany. Germany trembles before yet more prolific Russia. Europe fears the awakening of the teeming yellow race. In South Africa, the whites stand aghast at the rabbit-like increase of the blacks.

Concerns over competitive fertility and differential population growth exist in all stratified political economies and give rise to strategic demographic considerations and to the development of population policies and programs that address such concerns. Thus, where unequal power relations exist, those social groups, or political entities, with greater power will direct population policies and programs against those groups with less power whose population growth is considered a threat to existing power relations. Such strategic demographic policies are not necessarily undertaken as a conscious attempt to dominate or control subordinate populations, but rather are largely undertaken because they reflect a dominant group’s collective perception of why prevailing socioeconomic differences exist, as well as its explanation for how its members have come to occupy a position of dominance.

Malthusian population theory must, therefore, be understood not as an environmentalist treatise, as it is so frequently presented, but rather as a sociopolitical product of the political economy of England in the early 19th century. Malthus’ primary motivation for writing Principle of Population was his opposition to the English Poor Laws. Malthus, like many others of his day, was genuinely concerned with the social, economic, and political consequences of the growing number of poor people crowding into London, Birmingham and the other urban areas of England. Malthus, a member of the social upper class, attributed poverty to irresponsible reproduction by the poor rather than to the changing structure of economic and political relations brought about by the industrial revolution. He, therefore, argued against remedial social policies; he believed such policies were counterproductive, because they would encourage the poor to breed and, thus, perpetuate both their poverty and their drain on public resources.

A concern with competitive fertility and a belief in the necessity of implementing strategic demographic policies designed to combat the reproduction of the poor are as central to contemporary neo-Malthusians as they were to the Malthusians before them. Frank Notestein, the initial head of the United Nations Population Commission, expressed what he believed was the need to provide population control in the Third World. Notestein (1944:158) considered it inappropriate to provide developmental assistance to the newly emerging nations following World War II without applying explicit population control measures. He believed that such a policy

. . . would yield populations that would be larger and stronger than those that would arise from the perpetuation of past [colonial] policies . . . The now dominant powers would in effect be creating a future world in which their own peoples would become progressively smaller minorities, and possess a progressively smaller proportion of the world’s wealth and power.

The British Royal Commission on Population in 1946 shared Notestein’s apprehension. The Royal Commission's concern went beyond the simple issue of economic and political power, however, and expressed a broader concern with the survival of Western values. According to the Commission, a decrease in relative Western population size "might be decisive in its effects on the prestige and influence of the West. … The question is not merely one of military strength and security: it merges into more fundamental issues of the maintenance and expansion of Western views and culture." (quoted in Furedi 1997:57). Paul Kennedy (1993:46) expressed essentially the same concern more recently when he asked if democratic values can maintain their prevailing position in “a world overwhelmingly peopled by societies which did not experience the rational scientific and liberal assumptions of the Enlightenment."

Much of the concern over population growth during the 1950s and 1960s was expressed within the competitive political framework of the Cold War. For this reason, the primary focus at that time was on population growth in Asia. Kingsley Davis (1959; quoted in Wilmoth and Ball 1992:647), one of the foremost demographers of the time, expressed concern that "China with a projected 1975 population almost double the expected figures from the United States and Russia combined, would be the strongest contender for world leadership. Such a mass, equipped with modern arms and disciplined by a dictatorship, if bent on conquest, could be stopped only by a united world outside." Similarly, John Robbins (1959) stated, “there are too many Asians for their own good. They have been breeding trouble for themselves --and for the world as a whole.” The following advertisement by the Campaign to Check the Population Explosion reflects a rather common view of population growth that prevailed during the Cold War.

The ever-mounting tidal wave of humanity now challenges us to control it or be submerged along with all our civilized values. … A world with mass starvation in underdeveloped countries will be a world of chaos, riots and war. And a perfect breeding ground for Communism. … We cannot afford a half a dozen Vietnams or even one more. … Our own national interest demands that we go all out to help the underdeveloped countries control their population (quoted in Hartmann 1987:104).

Concerns regarding the effect of Third World population growth on the balance of power in international relations continued to be expressed, even after the end of the Cold War. Robert MacNamara (1984) voiced this concern, as did Nicholas Eberstadt of the American Enterprise Institute. Eberstadt (1991:127) maintained that the implications of current trends in population growth for the international political order and the balance of world power would be enormous: "Diminution of the influence of the West could create an international environment even more menacing to the security prospects of the Western alliance than was the Cold War." Timothy Wirth (1993:590-591), formerly with both the U.S. State Department and the World Bank, also expressed his concern over the relative decline of Western influence: "At the end of World War II, the developed countries accounted for almost 40 percent of the world population. Today they hold about 20 percent, heading --if growth in the developing countries does not slow-- towards as little as 12 percent (Wirth 1993:590-591).” For Wirth, “the cost of our population program is a fraction of not doing it (ibid.).”

THE

MALTHUSIAN SOLUTION

Malthusians have consistently attributed population growth to the inability or unwillingness of specific individuals or social groups to behave responsibly and control their reproduction. Karl Sax (1945:266), an American Malthusian, blamed poverty on those who “breed without consideration of economic and social consequences" and expressed the opinion that "nations which control their birth rates in order to maintain a higher standard of living" were not obliged to assist those that did not. In a similar vein, Frank Lorimer (1969; quoted in Furedi 1997:62), a prominent sociologist, blamed the “greater prolificacy of the non-white population” on the “less restrained reproductively of those with meager schooling.” while Garrett Hardin (1968, 1974) blamed overpopulation on the unwillingness of some individuals to practice reproductive restraint.

Malthusians did (and do) not view fertility systemically as a dependent variable influenced by infrastructural considerations, including, for example, the impact of female labor participation on reproduction or the role of children in the domestic economy. Rather, parental reproductive behavior was (and is) viewed largely as being independent of the socioeconomic context within which it occurs, and emphasis (blame) is placed on the attitudes and motivations of the individuals involved, which need changing (c.f. Ryerson, 2002). The elitist orientation of Malthusian population theory provided a rather easy justification for the application of coercive measures of population control, because the policies and programs were seen as being applied to intellectually, morally and/or culturally inferior individuals and social groups. Malthus himself encouraged the use of severe policies to control the reproduction and numbers of the poor.

Instead

of recommending cleanliness to the poor, we should encourage contrary

habits. In our towns, we

should make the streets narrower, crowd more people into the houses, and

court the return of the plague. In

the country we should build our villages near stagnant pools. …

But, above all, we should reprobate specific remedies for ravaging

diseases. (Malthus 1826:Book 4, Chapter 5)

NEO-MALTHUSIAN

POPULATION CONTROL POLICIES

It would be both inaccurate and unfair to completely equate contemporary population control programs with those of the early 20th century, at least as regards the blatant racism of those previous programs and the extreme policies that were proposed. However, contemporary neo-Malthusianism may rightfully be seen as the heir of these earlier programs, at least as regards the sociopolitical function that this latter demographic ideology performs. Contemporary neo-Malthusian population theory represents but a “kinder and gentler” form of Malthusianism. All of the underlying assumptions of Malthusian population theory are more or less fully accepted by contemporary neo-Malthusians. The principal difference is that neo-Malthusian population policies attempt to control population growth through reduced fertility in order to avoid the predicted increased mortality. However, although the methods that have been considered permissible by contemporary population control advocates may be different than those proposed in the past, the solution remains the same --a reduction in the number of the "wrong kinds of people." (see Haynes 1999). From a sociological or anthropological perspective, neo-Malthusian theory operates within the global community just as Malthusian theory did previously within Western societies -as a political ideology which functions: (1) to blame the poor for their poverty; and (2) to legitimize the control of those in power over the reproduction of the poor.

As with earlier Malthusians, contemporary neo-Malthusians rarely question their right to influence and interfere with reproductive and demographic processes in non-Western countries. The general acceptance of this right was expressed rather clearly by Kingsley Davis (1982):

Why does the family planning movement … which is the predominant approach to population policy, have as its slogan ‘every woman has the right to have as many children as she wants’? We would not justify traffic control by saying that ‘every driver has the right to drive as he pleases.’

While previous Malthusian policies were directed at the lower classes within Western society, neo-Malthusian population control programs are directed largely at non-Western peoples whose values and lifestyle are considered different from, and inferior to, those in the West. Contemporary neo-Malthusians expect non-Western peoples to adopt the reproductive behavior and values that they deem acceptable and, like Malthusians, have been fully prepared to coerce such peoples into practicing “acceptable” behavior, if necessary.

Several prominent neo-Malthusian spokespersons and population policymakers have openly endorsed the use of coercion in population control. In one scholarly review of the circumstances under which coercive population control policies would be acceptable, Berelson and Lieberson (1979:609) conclude that the “degree of coercive policy brought into play should be proportional to the degree of seriousness of the present problem and should be introduced only after less coercive means have been exhausted. Thus, overt violence or other potentially injurious coercion is not to be used before noninjurious coercion has been exhausted (emphasis mine).” Although Berelson and Lieberson placed limits on precisely when the use of “injurious” economic, political or physical forms of coercion would be acceptable in international population control programs, they did not question the legitimacy of program personnel using such coercion to achieve their goals.

Similarly, as President of the World Bank, Robert McNamara praised Indira Gandhi for establishing Emergency Rule in India in 1975, which resulted in the forced sterilization of several million men. McNamara praised “the political will and determination shown by the leadership at the highest level in intensifying the family planning drive with rare courage and conviction. (quoted in Hartmann; 1987:238)” Paul Ehrlich criticized the U.S. for not supporting Gandhi’s policy for the mandatory sterilization of all Indian men with three or more children. Ehrlich maintained that the U.S. “should have volunteered logistical support in the form of helicopters, vehicles and surgical instruments. We should have sent doctors (ibid.)." Addressing the issue of whether this constituted coercion, Ehrlich commented, "Perhaps, but coercion in a good cause (ibid.)." The Population Crisis Committee expressed concern over whether Gandhi's Emergency Rule would be implemented effectively: "For a coercive program to work, a hugely expanded commitment of administrative and financial resources will be necessary. The world will be watching India’s policy closely to see if and how state governments follow up their new legislation with bigger budgets and more effective action. (quoted in Hartmann 1987:342, note 29)" Garrett Hardin (1968; 1974) has also been an outspoken advocate of coercive population control policies.

Finally, while some international criticism has been directed at China’s strict one-child policy, most of it has targeted the policy’s gender implications, not its coercive practices. Some within the population control establishment have actually praised the Chinese policy, including Walter Holzhausen, Director of the UNFPA in Bangladesh. According to Holzhausen, "most donor representatives here greatly admire the Chinese for their achievements: a success story brought about by massive direct and indirect compulsion. … It is time for donors to get away from too narrow an interpretation of volunteerism, and certain governments in Asia using massive incentive schemes, including disincentives and other measures of pressure, still deserve international support (Hartmann 1987:212).” Significantly, both Indira Gandhi and Qian Xinzhong (China’s Family Planning Minister) received the U.N.’s Population Award for “the most outstanding contribution to the awareness of population questions.” (Hartmann 1987:155).

CONCLUSION

For more than 50 years, many people throughout Europe and North America have expressed a growing concern with overpopulation, and a powerful lobby has emerged whose goal has been to implement population control policies that will reduce global population growth. For the most part, these policies have been directed at the developing countries of the world. Significantly, the population lobby’s justification for implementing population control policies and programs has undergone repeated change during the last half century. Population control has been vigorously promoted as necessary to: (1) reduce poverty and underdevelopment, (2) prevent political instability, (3) protect the environment, and (4) promote women’s health and human rights. However, while the justification for population control has historically changed in the face of failed predictions and contradictory research, the concern with implementing population control has continued.

This paper has argued that the underlying cause for the persistent concern with overpopulation has more to do with the competitive implications of population growth in developing countries for those in the developed countries than with the reasons more commonly accepted. The paper suggests that the real concern is with the threatened change that population growth among developing (non-Western) countries portends for existing global political and economic relations and, thus, for the relative loss of power by the economically and politically dominant societies. The paper also suggests that neo-Malthusian population theory functions as a political ideology directly descended from Malthusian population theory and that, being directed explicitly at non-Western peoples, it represents the interests of the globally dominant populations and justifies their use of coercive social policies against peoples who are not only considered socially and morally inferior to those in the West, but who are also (through a denial of history and existing global economic and political inequalities) held individually responsible for their current condition of poverty and underdevelopment.

REFERENCES

Berelson, B. and J. Lieberson, 1979. Government Efforts to Influence Fertility: The Ethical Issues. Population and Development Review 5: 581-613.

Boserup, E., 1965. The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change under Population Pressure. Aldine-Atherton, Chicago.

Davis, K., 1992. Population Control Cannot Be Painless. People (IPPF) 9 (4).

Eberstadt, N., 1991. Population Change and National Security. Foreign Affairs, Summer: 115-116.

Ehrlich, P., 1968. The Population Bomb, Ballantine, New York.

Ehrlich, P.,1969. Eco-Catastrophe. Ramparts 8 (3): 24-28.

Furedi, F., 1997. Population and Development: A Critical Introduction, St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Hardin, G., 1968. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 162: 1243-1248.

Hardin, G., 1974. Living on a Lifeboat. BioScience 24: 561-568.

Harrison, P., 1993. The Third Revolution: Population, Environment and a Sustainable World, Penguin, London.

Hartmann, B., Reproductive Rights and Wrongs: The Global Politics of Population Control and Contraceptive Choice, Harper and Row, New York.

Haynes, M., 1999. The Latest Alibi: Subtle Racism Underlies Population Controllers 'Women's Rights' Agenda. Population Research Institute Review 9.

Homer-Dixon, T.F., J. H. Boutwell and G.W. Rathjens, 1993. Environmental Change and Violent Conflict: Growing Scarcities of Renewable Resources Can Contribute to Social Instability and Civil Strife. Scientific American 268 (Feb): 38-45.

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, 2001. World Development Report 2000/2001: Attacking Poverty. Oxford University Press, New York.

Kokole, O.A., 1994. The Politics of Fertility in Africa. In: The New Politics of Population, J.L.Finkle and C.A. McIntosh (eds.), The Population Council, New York.

Lomborg, B., 2001. The Skeptical Environmentalist, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Lorimer, F., 1969. Issues of Population Policy. In: The Population Dilemma, P.M. Hauser (ed.), Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Lugo, A.E., 1988. Estimating Reductions in the Diversity of Tropical Forest Species. In: Biodiversity, Wilson, E.O. and F.M. Peter (eds.), National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., pp. 58-70.

MacNamara, R.C., 1984. Time Bomb or Myth: The Population Problem. Foreign Affairs. Summer.

Malthus , T.R., 1826. An Essay on the Principle of Population, Sixth Edition. Library of Economics and Liberty. Retrieved May 31, 2002 from the World Wide Web:

Mann, C., 1991. Extinction: Are Ecologists Crying Wolf? Science 253: 736-738.

Meadows, D.H., D.L. Meadows, J. Randers, and W. Bherens III, 1972. The Limits to Growth, The American Library, New York.

Mortimore, M., 1993. The Intensification of Peri-Urban Agriculture: The Kano Close-Settled Zone, 1964-1986. In: Population Growth and Agricultural Change in Africa, Turner, B.L. Hyden, G.L. and Kates, R.W. (eds.). University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp.358-400.

Mortimore, M. and M. Tiffen, 1994. Population Growth and a Sustainable Environment: The Machakos Story. Environment 36: 10-25.

Myers, N., 1979. The Sinking Ark, Pergamon, Oxford, NY.

National Research Council. 1986. Population Growth and Economic Development: Policy Questions, National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

Nowak, M., 1998. Our Demographic Future: Why Population Policy Matters to America. NPG Special Report.

Notestein, F., 1944. Problems of Policy in Relation to Areas of Heavy Population Pressure. Demographic Studies of Selected Areas of Rapid Growth, Proceedings of the Round Table on population Problems, twenty-second annual conference of the Milbank Memorial Fund, New York: April 12-13, pp. 138-158.

Paarlberg, R.L., 1994. The Politics of Agricultural Resource Abuse. Environment 36: 6-19.

Robbins, J. 1959. Too Many Asians. Doubleday, Garden City.

Ross, E.A., 1907. Western Civilization and the Birth Rate. American Journal of Sociology 12: 607-632.

Ryerson, W., Sixteen Myths about Population. Population Media Center.

Sax, K., 1945. Population Problems. In: The Science of Man in the World Crisis, R. Linton (ed.), Columbia University Press, New York.

Simberloff, D., 1992. “Do Species-Area Curves Predict Extinction in Fragmented Forests?” In: Tropical Deforestation and Species Extinction, Whitmore, T.C., and J.A. Sayer (eds.), Chapman and Hall, London, pp. 75-90.

Stork, N.E., 1997. Measuring Global Biodiversity and its Decline. In: Biodiversity II, M.L. Reaka-Kudla, D.E. Wilson and E.O. Wilson (eds.), Joseph Henry Press, Washington, D.C., pp 41-68.

Tiffen, M., M. Mortimore and F. Gichuki, 1994. More People, Less Erosion: Environmental Recovery in Kenya, J. Wiley, New York.

Turner, B.L. Hyden, G.L. and Kates, R.W., 1993. Population Growth and Agricultural Change in Africa, University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Vogt, W., People! Challenge to Survival. 1960, W. Sloane Associates, New York.

Warrick, J., 1998. Mass Extinction Underway, Majority of Biologists Say. Washington Post. (April 21, 1998).

Weeks, J., 1999. Population: An Introduction to Concepts and Issues, Wadsworth, Belmont, CA.

Wilmoth, J.W. and P. Ball., 1992. The Population Debate in American Popular Magazines, 1946-90. Population and Development Review 18: 631-668.

Wirth, T.E., 1993. U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations Hearings on Foreign Operations, Export Financing and Related Programs, 103d. Congress, First Session, Part II (February-June 1993; submitted statement, June 11, 1993)

World Health Organization, 2001. Healthy Life Expectancy, World Health Report 2001.

* * * * *

Of Related Interest:

|

|

|

Ecological Theory and the Evolution

* * * * *